When Theresa May invokes Article 50, the formal trigger on Britain’s exit from the European Union, multiple and multi-layered negotiations will begin. So far, the EU has maintained a united front on Brexit—“no negotiation before notification.” But once the real discussions begin, facing Britain across the table will not be one person, but a set of different actors with different roles and responsibilities, and each under different pressures.

As Britain demands a previously unavailable mix of national immigration control and international trading rights, the day-to-day discussion will be managed by a trio of less familiar names, appointed by the three main EU institutions to hold the Brexit ring.

Ultimately, though, the "negotiating buck" will stop with the national governments of the EU 27 and they have a range of mechanisms, both institutionalised and informal, to enable them to coordinate their positions alongside and with the key EU institutions. However, given the unprecedented domestic pressures facing many of them, they will likely be pulled in many different directions.

So what do we know about the three “Brexit leads” who could ultimately determine the UK’s fate? What formal powers do they have? How will they navigate the fiendish mix of institutional and national interests that must be respected and balanced in any outcome? What are some of the national agendas and red lines that might upset negotiations? And what attitude will each adopt towards anything that sounds like British special pleading?

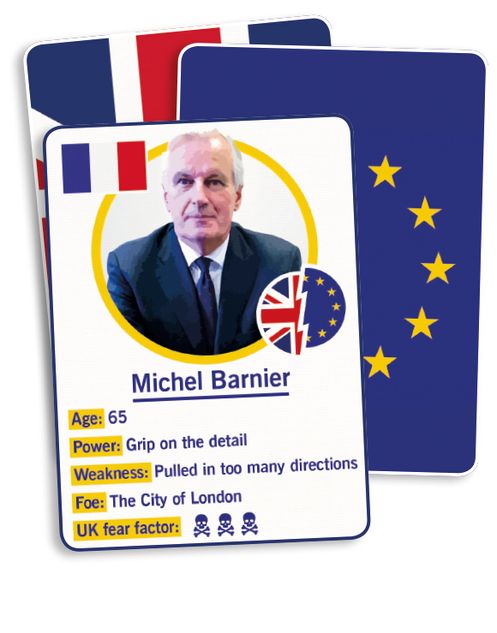

Chief Negotiator for the Preparation and Conduct of the Negotiations with the United Kingdom, European Commission

The European Commission President, Jean-Claude Juncker, said he “wanted an experienced politician” for the “difficult job” of negotiating Brexit, and in Michel Barnier he has found one. Twice a European Commissioner, four times a French minister, and briefly an MEP, Barnier is just as comfortable in Brussels as he is in Paris. Hailing from one of the two biggest EU states, and buttressed by a deputy from the other (the veteran Commission trade negotiator Sabine Weyand is German), for Barnier, navigating the relationships between national capitals and EU institutions is second nature.

Nicknamed the “scourge of the City” by the British press during his stint as Single Market Commissioner, when he oversaw the post-crisis regulatory crackdown on Europe’s financial services sector, his appointment signals the EU’s willingness to play tough.

He is also, however, a pragmatist. Thus, while he will be determined to prevent other states from succumbing to what one official describes as “the English disease,” he will be keen to ensure as smooth a departure for Britain as is compatible with that aim.

Juncker will never be far away, and his mood could be bleak following sustained criticism for his handling of the various crises confronting the EU, including the UK’s referendum vote. Meanwhile, Juncker’s right-hand man, his powerful and polarising chef de cabinet the “arch-federalist” Martin Selmayr, will likely figure as a behind-the-scenes enforcer. He’ll certainly be pressing to prevent Britain receiving special treatment.

The member states will be looking to keep Barnier on a tight rein: in Berlin, Angela Merkel remains deeply concerned about the potential for further fragmentation; in Paris, the over-riding concern will be making sure nothing is done to further embolden the ascendant Europhobic Front National of Marine Le Pen; and to the East, the Visegrad Four (Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia) will want to defend their citizens’ freedom to work in the UK, at the same time as fiercely resisting any attempts to use Brexit as an excuse to push for more integration.

Last but not least, the European Parliament will remind him constantly that no deal he does can stand until it has secured the approval of elected MEPs. And all of these pressures will become more intense as the negotiations approach decision time.

In sum, Barnier is going to need every ounce of his considerable diplomatic nous simply to retain the support of all the forces he is negotiating for—forces which do not include Britain.

Representative for Brexit negotiations, European Parliament

The most instructive guide to Guy Verhofstadt might be to look at his enemies. When this straight-talking, social media-savvy former Belgian premier was named as the European Parliament’s point man on Brexit, Nigel Farage called it a “declaration of war”; David Davis only managed a half-joking “Get thee behind me, Satan.” A born politician and consummate negotiator, he is one of Europe’s last unabashed federalists.

He is, however, unlikely to be as anti-British as some fear. Now the leader of the liberal democratic bloc in the European Parliament, he was once nicknamed “Baby Thatcher” for his free market views. More importantly, he will not enjoy a free negotiating hand. In fact, the parliament does not officially sit in on the negotiations at all. His leverage arises only because MEPs must sign off on the withdrawal agreement and any future trade deal: he’s not so much holding an ace, as wielding a threat to kick over the card table. But it would not be wise for Britain to dismiss the influence this affords. While it is unlikely that MEPs will reject a final deal, the mere possibility will force the negotiators to factor in objections in advance.

The EU has a well-oiled machinery to ensure that issues of concern in one institution become known to another, and Verhofstadt is a skilled operator in this milieu. He will work with the parliament’s president as well as party group and committee chairs. This will include Manfred Weber, leader of the conservative EPP group and a close Merkel ally, and Elmar Brok, the influential and experienced Foreign Affairs Committee Chair. Both share his support for “ever closer union” and his opposition to granting Britain a special deal on freedom of movement in return for single market access. This increases the possibility that a “European Parliament view” will emerge, which increases the institution’s power.

At the same time there will be opportunities for Verhofstadt’s personal convictions to shine. He has long mooted “associate membership” status for Britain, and will push for ambitious, out-of-the-box EU reform. Contrary to the views in many capitals, he believes this requires “more Europe,” not less. “The negotiations,” he recently declared, “are about more than merely settling a divorce with the UK. They are about the future of Europe.”

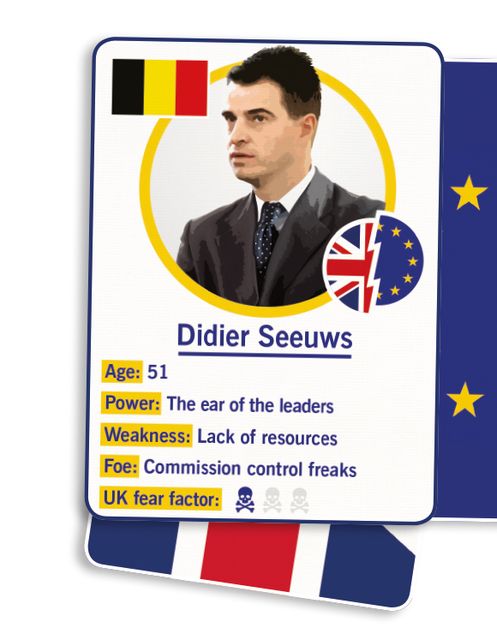

Head of the Task Force on the UK, Council of the European Union

The Commission, the executive body of the EU, was decidedly miffed when the Council, the forum in which the member states’ ministers meet, designated Seeuws as head of its own dedicated Brexit Taskforce. Some saw this as an attempt to clip the Commission’s wings. But his appointment reflects the reality that whatever the legalities and technicalities, a crisis on the scale of Brexit is inevitably a political matter. The departure of any state from the EU would be of grave concern for Europe’s leaders; all the more so when the state in question is Britain, a big economy and a net contributor to the budget. Whatever the posturing of the Commission or MEPs, national leaders consider Brexit to be their business, and it falls to Seeuws to see that it stays that way.

Seeuws is impeccably qualified for the role. He has been his country’s former Deputy Permanent Representative to the EU, and served as spokesman for Verhofstadt when he was Belgian PM. He also spent two years as chef de cabinet for the former European Council President Herman van Rompuy. He is therefore supremely well-versed in the intricacies of Brussels deal-making, and all the sensitivities that come with it.

Chief among those will be knowing the constraints he must work within. He will understand that the Council lacks the legal and technical resources to lead the day-to-day process of detailed negotiation: that is the Commission’s task. Rather, Seeuws will support the Council in setting a broad strategy, and scrutinising the Commission’s execution of its negotiating mandate. When domestic political pressures inevitably pull the leaders on the Council in competing directions, this will be no easy task. But with a direct route-in to all the leaders of the remaining EU-27, Britain’s potentially isolated negotiators would be very wise to heed Seeuws’s advice about ways to proceed.

Angela Merkel,

German Chancellor

While coordination and consensus-building is a core principle of the Union, the governments of the EU 27 will necessarily hold competing, sometimes even incompatible views. They also have different amounts of leverage in the political bargaining that is about to start. Among them, Merkel is no doubt primus inter pares.

The former scientist is known for her no-nonsense, methodical style. Yet she also retains a deeply value-based vision of European integration and its inherent fragility. Despite being well-disposed toward Britain, a liberal economic ally whose exit she deeply regrets, her top priority has always been the EU. Indeed, as Westminster leans more towards leaving the Single Market, Merkel’s stance has hardened. The UK may be Germany’s third-largest export market, solidarity with the Single Market will be more important to her than the amount Germany trades with us. And she has rejected the possibility of Britain receiving special treatment when it comes to the so-called “four freedoms”—of goods, people, services and capital—saying this would represent “a systemic challenge for the entire European Union.” That said, she recently seemed to indicate that some EU-wide reforms on free movement could be on the cards.

While taking the lead on Brexit, Merkel can rely on trusted allies, from veteran Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble to up-and-coming European Affairs Minister Michael Roth. But this challenge comes at a sensitive moment for her. Merkel’s liberal refugee policy has won her many enemies. After more than a decade in power, support for her and her party, the Christian Democrats, has plummeted—just as she faces re-election. Domestically, the far-right, anti-EU Alternative für Deutschland continues to siphon off votes. She also needs to face down other key players, from Italy’s Matteo Renzi to Jean-Claude Juncker, to defend her vision of the EU27, which involves fiscal restraint and intergovernmental, rather than supranational, coordination.

Brexit will multiply and intensify these conflicts.

Francois Hollande (or his successor)

French President

France is holding presidential elections next year, and polls indicate that Francois Hollande is unlikely to be re-elected, with the centre-right’s Alain Juppe, a former prime minister, well-placed to succeed him. Whoever wins (assuming a major upset does not see victory for Marine Le Pen and the far-right Front National) there will be little difference to France’s position on Brexit negotiations. While the next president will expect to exercise significant influence over the negotiations, they will also be operating within clearly defined parameters.

Since the immediate post-referendum calls to “make Britain pay,” France’s position has softened, becoming more pragmatic. It will have three key objectives: first, to maintain the integrity of the post-Brexit EU, not least in the face of domestic pressure from anti-EU populists; second, to remain in lock-step with Berlin, reflecting the foundation of integration and the reality that French influence is greatest when working with Germany; and third, to ensure a strong post-Brexit bilateral relationship with the UK, particularly in security and defence, where the UK will likely remain France’s key European partner.

Balancing these aims will be challenging. Anglo-French relations have been tested by the migration crisis in Calais, while France will remain alert to Berlin’s positioning, fearful Germany might “go soft” on the UK in the final agreement. Ultimately, Paris must tread a fine line between managing its future relations with Britain and ensuring that Brexit does not cause further European fragmentation. The appointment of Barnier will reassure France’s political leadership that their concerns will not be ignored.

The Visegrád Four

Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia

An alliance of four Central European states that joined the EU in 2004, the “V4” are seizing on Brexit as an opportunity to advance their interests. In the context of domestic backsliding towards authoritarianism, and propped up by public fatigue of post-accession democratic reforms, the governments of Hungary and Poland in particular have taken a defiant stance toward the Union. Britain was a key supporter of the V4’s EU membership. Now it’s on the way out, they too think that the EU is at a historic turning point—but have a different perspective to many of their peers.

The V4’s demands for curbing Brussels’ powers, most recently presented at the Bratislava summit, and their warning about drawing the “wrong” (read: integrationist) conclusions from Brexit, may no longer sound too radical. But their opposition to migrant quotas to tackle Europe’s refugee crisis threatens to undermine the EU’s institutions. Furthermore, although Slovakia and the Czech Republic strive to distance themselves from some of the fiercer rhetoric, the V4 represent a break with the European consensus. The illiberalism of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, along with the ultra-conservatism of the Chairman of Poland’s Law and Justice Party Jarosaw Kaczyski, could herald a new east-west divide.

It certainly spells trouble for the upcoming negotiations. The V4 fear a geopolitical shift eastward that would benefit Germany, a push for further eurozone integration, and the emergence of a two-speed Europe in which their priorities would rank lower. Poland is already manoeuvring against European Council President and former Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who is much closer to Merkel in his politics than to his compatriots. But the V4’s emergence as a united opposition bloc will not necessarily turn the negotiations in Britain’s favour. The four countries have promised to fight any limits on the rights of their citizens to work in the UK. Given Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico's recent threat to veto any agreement that would turn the EU migrant population in Britain into “second-class citizens,” the stakes will be high.

*

The big challenge facing leaders of the EU-27 is to demonstrate the benefits of continuing membership to increasingly sceptical electorates. With elections pending in France and the Netherlands, and in the wake of the US presidential elections, the stakes are as high as they could be. Expect strong resistance, therefore, to any deal perceived to leave the UK better off outside the EU. And don’t bet too much on the economy either. Influential business groups on the continent have already signaled that between access to the UK and the integrity of the Single Market, the latter may be of greater significance to them.

David Davis is apparently relishing the prospect of lining up once more against EU officialdom in the forthcoming negotiations. Nicknamed “the charming bastard” by his European counterparts during his time as Minister for Europe in John Major’s government, he finds himself today in a career-defining post. Achieving victory in the referendum may prove to have been much easier than making Brexit a reality.

Card illustrations created and written by the Prospect team

Meet the Brexit Brokers

Meet the people who will deal the cards that could seal Britain's fate—on Europe's behalf

November 10, 2016

Michel Barnier in 2015 ©Wiktor Dabkowski/DPA/PA Images