Britain is likely to say a clear but reluctant Yes to staying in the European Union in the coming referendum. We don’t like or trust the EU, but we doubt whether Britain can prosper if we left the club. It will be a majority based on fear, not love.

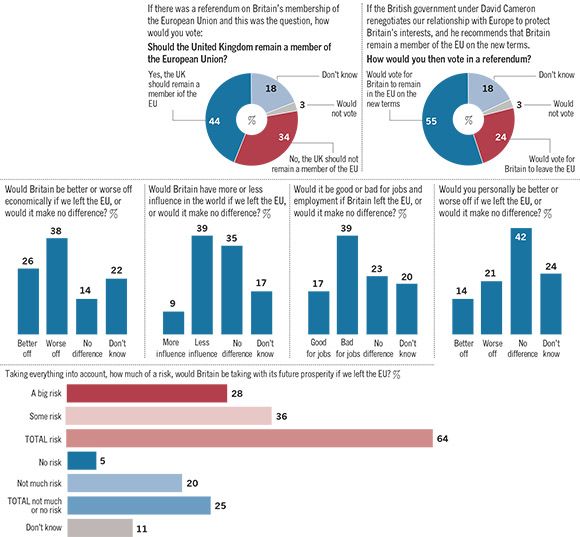

This month’s YouGov poll for Prospect is the first to ask the precise question that the government plans to put on the ballot paper: “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union?” We found a 10-point lead for Yes: 44-34 per cent. Leaving aside those who say “don’t know” or would not vote, this equates to a 57-43 per cent vote to stay in the EU.

It’s a comfortable lead, and consistent with other surveys YouGov has conducted this year, asking the question slightly differently. However, on its own it does not mean that a Yes majority is inevitable. It needs only a modest shift for the lead to disappear—and remember how much opinion oscillated in Scotland last year, before the country voted by 55-45 per cent to remain in the UK. And it’s not long since we had more people wanting to leave the EU than remain a member. No was ahead as recently as last November; and just three years ago, it led by as much as 64-36 per cent.

Nor should those figures cause surprise. We have been tracking trust in elite groups for some years, and consistently find that “senior officials in the EU” are trusted even less than British politicians and civil servants. Our annual polls for Chatham House find that clear majorities of Britons resent EU laws and regulations, and blame the EU for the influx of immigrants.

Even so, our latest poll for Prospect shows why the Yes campaign has an advantage in the coming referendum campaign—as long as David Cameron recommends staying in the EU. We asked: “Imagine the British government under David Cameron renegotiated our relationship with Europe and said that Britain’s interests were now protected, and David Cameron recommended that Britain remain a member of the EU on the new terms. How would you then vote in a referendum on the issue?”

This time, the Yes lead widens to more than two-to-one. In these circumstances, every political and demographic group moves towards Yes, but Conservative voters most of all. They move from 52-48 per cent against membership on the initial question to 74-26 per cent in favour of membership on the conditional question.

Our other findings help to explain why support for No has declined in recent months. We asked about Britain’s prospects if it left the EU. Britain’s business community, though not unanimous, has started to warn loudly that Brexit would be bad for jobs and investment. Our poll finds that these argument have a strong resonance.

Our most striking result is that fully 64 per cent of the public think Britain would be taking a “big risk” or “some risk” with its future prosperity if we left the EU. Just 25 per cent think there would be “not much” or “no risk.” Even among those currently inclined to vote for Brexit, one in three think that our future prosperity could be at risk. We then asked about different features of life outside the EU. In each case large numbers say “don’t know” or “it would make no difference.” But of those who do take sides, many more on each issue say things would be worse not better.

That, then, is a snapshot of how things are now. Attitudes may change. Europe is not a major issue for most voters, and many of them have yet to focus on the issue. Past experience of referendums, including the 1975 vote of whether to remain in the Common Market (as it then was), suggest that people without strong convictions are more likely to end up backing the status quo rather than voting for change.

But we can’t be sure. Various things could lift the No vote. A scandal or crisis in the EU during the campaign would lead voters to say we would be better off going it alone. A sustained No campaign by the Sun and/or Daily Mail, with daily exposés, fair or unfair, of the EU’s supposed iniquities. Conflicting messages from different Yes camps with, for example, Cameron and Nicola Sturgeon saying diametrically opposed things.

Alternatively, and most dramatically of all, if Cameron is forced to concede that his negotiations have failed, he could end up recommending a No vote. If he does end up campaigning for Brexit, then one of two things will happen.

The first is that a majority across the UK might vote No. But that majority is likely to exclude Scotland, which will probably vote Yes by at least 60-40 per cent; so future relations between Westminster and Holyrood will become as fraught as those between London and Brussels.

The second is that the UK still votes Yes and Cameron ends up on the losing side. Either way, a No recommendation in the referendum will make UK politics intensely interesting, and not necessarily in a good way.