Being aboard the HMS Prince of Wales is like standing on a little bit of England, moored off Liverpool. I was six decks up on the 65,000-tonne aircraft carrier, on a flight deck the size of three football pitches. An hour earlier, I was on the floating concrete jetty against which the vessel was docked, watching the incongruous sight of vans parked on the platform bobbing with the tide.

Aircraft carriers have this effect: they blur the line between land and sea. They are less airstrips put to water than airport terminals that one can steer. On other Navy ships, crew use large ocean swells to “deck jump”—leap at the right point in the ship’s pitch, and you can skip most of the stairs. But on a vessel the size of HMS Prince of Wales, the crew must climb.

On board, there is a bar, a bakery, a coffee shop, a mini-mart, a cinema, a chapel, four large dining areas and five gyms, all geared towards a crew of at least 700 deployed at sea for months on end. When fighter jets are added, for a large-scale operation, the crew can swell to 1,600—at which point, I’m told, even a ship that’s the length of the Palace of Westminster starts to feel small. Yet, despite this—and despite all crew being supplied with handheld navigational devices—those who’ve been on board for months can still sometimes get lost.

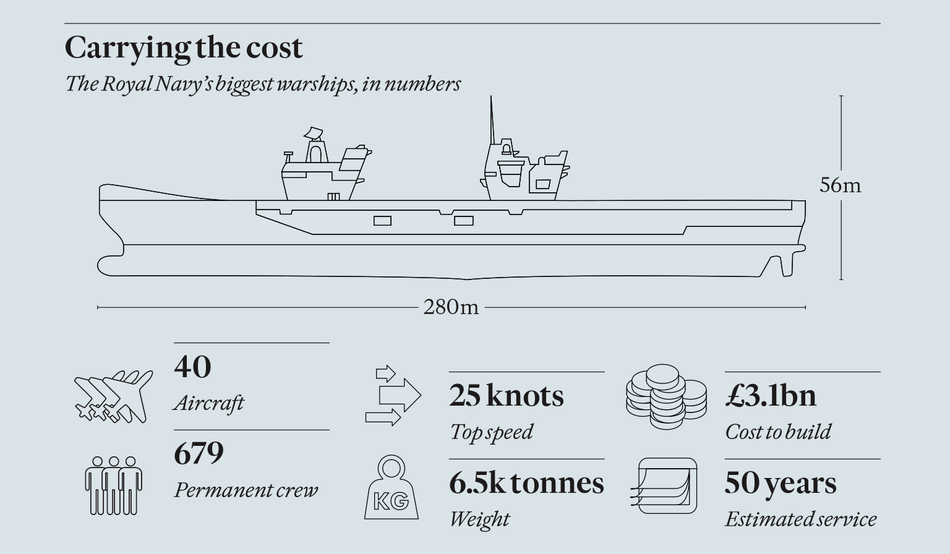

I was there to mark a milestone of sorts: HMS Prince of Wales was taking over as the Royal Navy’s flagship from HMS Queen Elizabeth. Together, the two sister carriers had cost the government more than £6bn. HMS Queen Elizabeth came first, entering service in 2020, with HMS Prince of Wales not far behind.

Known as the Queen Elizabeth class, they are, by some distance, the largest vessels ever constructed for the Navy, three times the size of the Invincible-class -carriers they replaced. In order for them to enter Portsmouth Harbour, 3.2m cubic metres of material had to be dredged to deepen the waters. The dredging vessels found 96 cannonballs, a German sea mine and a human skull. In 2021, then prime minster Boris Johnson described the carriers as “a more eloquent statement, in many ways, than many of the speeches and interventions that we have heard this afternoon about Britain’s role in the world”.

Most agree—just not all for the reasons Johnson imagined.

Both carriers have been beset by problems: leaks, fires, propellers that have failed to propel. In May 2023, it was revealed that HMS Prince of Wales had spent a third of its active life in repairs. Last year, HMS Queen Elizabeth spent four months being serviced in Rosyth, Scotland, the same dry-dock in which it was built. Each of the ships are designed to carry up to 36 F-35B Lightning II fighter jets, yet only 37 in total were expected to have arrived by the end of 2024. In 2021, one fighter jet crashed on take-off from HMS Queen Elizabeth. It was later revealed a rain cover had been left on. But a far bigger concern is the carriers themselves: are they fit for today’s warfare?

The carriers were first conceived under Tony Blair and the first steel was cut under Gordon Brown. They were constructed under David Cameron, began sea trials under Theresa May, entered service under Boris Johnson, had propeller problems under Liz Truss, and were still being repaired under Rishi Sunak. Their history spans September 11, the war on terror, a global financial crisis, Brexit, Covid, the death of both Queen Elizabeth and the Queen Mother, and the invention of the iPhone.

In that time, critics point out, war has changed. Russia and China have developed hypersonic missiles—which travel at least five times the speed of sound, or Mach 5. In December, Vladimir Putin claimed Russia’s latest missile, the Oreshnik, travels at twice that speed, at Mach 10, and is impossible to shoot down. If true, it would pose an existential threat to carriers. When HMS Queen Elizabeth launched for its maiden voyage in 2017, the Russian defence ministry dismissed it as “merely a large convenient naval target”.

The war in Ukraine, meanwhile, has shown what can be done with cheap drone technology. Workshops behind the Ukrainian front line build more than 100,000 every month. At first, grenades were attached to off-the-shelf models to target Russian troops. But Ukraine has since developed drones that can carry 5kg warheads capable of taking out tanks. They cost less than £1,000 to produce. The tanks cost several million. Sea drones, costing around £200,000 each, have sunk Russian battleships worth billions.

Dominic Cummings, Boris Johnson’s former adviser, has suggested drones could even take out carriers. “A teenager will be able to deploy a drone from their smartphone to sink one of these multibillion-dollar platforms,” he wrote in 2019. Many military experts told me this isn’t true—but the doubt remains: have we built yesterday’s ships for tomorrow’s war? Or, perhaps worse, has Britain unwittingly sailed a metaphor for its current state out to sea? Two £3bn, 65,000-tonne symbols for the gap between how we see ourselves and how we are seen by others, for our misplaced self-regard, our pomp despite our circumstance?

In arguments about aircraft carriers—and there are many—proponents note that their fundamental virtues have not changed. They provide air support anywhere in the world without the need for foreign bases. They provide vital humanitarian relief at a moment’s notice. And, for an island nation that does 95 per cent of its trade by sea, they allow us to safeguard shipping just by showing up.

I asked Will Blackett, the commanding officer of HMS Prince of Wales, about the role of these carriers today. Are they more a symbol of power than power itself?

“It’s the same thing, it’s all influence,” he said. “We have to show people that we’re credible war fighters, then hope we never have to do it.” He added: “How many of these have you seen around the world? We’re one of a very small number of nations that have them. Also, see that bomb?” We were in the carrier’s vast hangar, where he gestured at a bomb that had had its warhead replaced by concrete—to be used in target practice. “We can drop that from a long way away and you won’t see it coming. So wouldn’t it be better to be our friend?”

A government strategic defence review launched last summer is set to report in the spring. Defence secretary John Healey hailed it as the first of its kind, drawing on military experts, along with those from industry and academia, to “take a fresh look at the challenges we face”. Most agree they have their work cut out.

At the Munich Security Conference in February, the speech by US vice president JD Vance ignored Ukraine and focused on the culture wars, only reinforcing the need for increased European spending on defence. Ahead of a meeting between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin to which the president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, has not been invited, Keir Starmer has promised British peacekeeping troops if any real deal can be made. The business secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, said the whole cabinet agreed defence spending must be increased.

Munitions, a senior source told me, are running perilously low, with those sent to Ukraine yet to be adequately replaced. Britain’s fleet of surface ships is threadbare, with several given early retirement in November. Our nuclear submarines are aging, with Dreadnought-class replacements not expected until the 2030s. The British Army has shrunk to its smallest size since the Napoleonic Wars.

Attention, inevitably, has come to rest on the carriers. Reports have suggested one could be “mothballed”—taken out of active duty—to save on costs. One senior source I spoke to, who has been consulted on the defence review, told me the government is seriously considering mothballing both. “They are really thinking of beaching these things,” he told me. “If you just take out one you don’t save much money.”

Of the people I spoke to for this story—Ministry of Defence (MoD) insiders, warfare experts, politicians—all agreed doing so would be a profound decision, but gave differing reasons as to why: that it would reflect current threats, modern technology, budgets that only stretch so far. But also, perhaps, something else.

In the military jargon, carriers are about “power projection”—the ability to influence the world beyond your borders. By giving them up, would Britain be accepting our diminished global status, or creating it? By keeping them, would we be committing to update them for a future of remote-controlled conflict, or for nothing more than pride—a reminder, both sad and nostalgic, of a time when Britannia still ruled the waves?

The history of aircraft carriers is surprisingly long. During the Austrian siege of Venice, in 1849, hot air balloons loaded with explosives were floated from SMS Vulcano, a paddle steamer, with the bombs activated by time fuses. The attack was not overly -successful. Only one balloon landed on Venice. Many drifted back towards the Vulcano after the wind changed. It managed to be simultaneously the first offensive use of air power in naval aviation, the first drone attack, and the first known incident of a ship carrying out a bombing raid on itself.

Most cite the Battle of Taranto in the Second World War as the birth of the modern carrier. In 1940, 21 virtually obsolete British biplanes, armed with torpedoes and bombs, launched from HMS Illustrious in the Mediterranean and disabled half the Italian fleet in a single night. Until then, ships were still slugging it out in a way that hadn’t changed much since the days of Horatio Nelson.

Military historians suspect Taranto influenced the planning of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the following year, when six Japanese carriers travelled 3,500 miles from Hitokappu Bay, positioned themselves 260 miles north of Oahu in Hawaii and launched 353 planes, the largest fleet the world had ever seen. We think of Pearl Harbor as an aerial assault, but it was the sea that made it possible.

By the time the US got its revenge in the Battle of Midway six months later—a carrier-on-carrier naval battle in which four Japanese carriers were sunk—American industry was producing a fleet carrier almost every month.

Hardware, of course, has always changed warfare. The increased range and power of rifles and artillery in the First World War meant the end of open battlefields and the advent of trenches. The new mobility of tanks and armoured vehicles in the Second World War, combined with air support and radio communications, allowed the German blitzkrieg.

But it’s perhaps only carriers that keep going in and out of favour. America had built a carrier fleet the envy of the world by the end of the Second World War but soon had -buyer’s remorse, thanks to Cold War -missile technology. Strategic nuclear bombing, via the new long-range B-36 “Peacemaker” that could get to Moscow and back, was seen as the best way to defend US interests. This approach caused such a kerfuffle in the US Navy that Time labelled it “the revolt of the Admirals”. But by the Korean War in 1950 carriers were back in vogue, with nuclear annihilation now seen as a bit extreme.

Until recently, the UK lagged far behind America in the carrier arms race. Before HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales, the Royal Navy had three “light” carriers—HMS Invincible, HMS Illustrious and HMS Ark Royal. Built in the 1970s, they weighed 22,000 tonnes and could each carry around 20 aircraft—tiddly compared to the 100,000-tonne US super-carriers that carry close to 100.

First deployed in the Falklands, by the time of the Gulf War the UK’s carriers were considered essential, and therefore needed replacing. A 1998 strategic defence review noted that the reluctance of all Gulf States but Kuwait to sanction use of their airfields earlier that year had severely hampered the air campaign.

The Navy would therefore change its focus. Other ships and submarines would be cut, “due to the reduced threat in UK waters” and operations around our coastline scaled back. Protection was out. Force projection was in. The implication was clear: we go abroad to fight wars. They don’t come to us.

But constructing these carriers was, predictably, a generation-length omnishambles. First, rows broke out about who would build them. It took until 2003 for the MoD to choose two “prime contractors”—BAE Systems and Thales. The vessels would cost £3.9bn in total and would arrive in 2012 and 2014. Except, of course, they wouldn’t.

Privately, contractors said those estimates were wildly optimistic. It wasn’t until 2008, under Gordon Brown, that contracts were signed. Two of the four sections of each ship would be built in Scotland: the Babcock yard in Rosyth, Fife would build the sterns, the BAE yard on the Clyde would make the bow. “Gordon Brown wanted the aircraft carriers because they were going to be built in the constituency next door to him,” says a source. The height of both ships had to be lowered so they could sail back under the Forth Rail Bridge when they were put together.

A significant delay was announced in 2008. Initially, John Hutton, then defence secretary, explained this had been done to align with the arrival of the planes that would fly from them. Except, of course, it hadn’t. The MoD was way over-budget, an insider tells me, and simply needed to kick the costs down the road. It asked the ship builders to delay. “The MoD were massively over-committed. And because they’re not very commercial, they were always surprised when defence contractors said yes.” The delay added £1.6bn to the overall cost. “Because you’re occupying the shipyard two years longer, you’re paying people for two years longer. They’re just working slower.”

When the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition came to power in 2010, it decided to re-examine the carriers. Following another strategic defence review, the government announced the carriers would be converted to a catapult launching system, and mocked Labour for making an “error” in the first place.

A catapult would enable use of the C variant of the new F-35 stealth jet, which boasts increased range and greater payload capacity compared to the B variant the carriers had been designed to use, and which takes off from a ski-ramp.

But an 18-month study saw the cost of an HMS Prince of Wales catapult -conversion alone swell to over £2bn—more than the original estimate for one entire carrier. “You had to cut a hole down seven decks,” says a source. HMS Queen Elizabeth, further along in the building process, would have cost even more to be converted.

Yet, I’m told, the Navy were unperturbed—and lobbied to ditch HMS Queen Elizabeth in order to pay for it: “The Navy’s proposal was literally to throw one of them away.” Eventually, the coalition did a U-turn on the U-turn. It also discovered the construction contract Labour had signed was unbreakable: even if a carrier was cancelled, the government would have to guarantee work for that period. It would cost more to ditch a carrier than keep it.

Yet it wasn’t all bad. No catapults meant reduced running costs, and less training for pilots. “With the F-35B, they press a button and the aircraft lands -vertically for them,” says Pete Sandeman, editor of the UK website Navy Lookout.

Electric propulsion for the ships—each generate enough power to light a large town—made them far easier to maintain than a nuclear-powered carrier. A highly automated weapons loading system that officers on HMS Prince of Wales refer to as “Bomb Amazon”—an allusion to the retailer’s warehouse robots—saved on yet more staff. In US carriers, loading is still done manually. In all, the Queen Elizabeth class can do with a complement of several hundred people what would be the work of several thousand on US carriers—essential, considering the Royal Navy’s recruitment problems.

Even the snags, once the carriers were at sea, weren’t quite as embarrassing as reported. Yes, there was a leak on HMS Prince of Wales, but an internal one—from a water main that runs around the ship. Yes, there was a fire on HMS Queen Elizabeth, but it was put out quickly. “They’re effectively prototypes that also have to be operational warships,” says Sandeman. “Inevitably, you have problems.”

I’m told the propeller-shaft issues on HMS Prince of Wales, however, almost certainly resulted from cost-cutting. The twin propellers weigh 33 tonnes each and generate enough power to run 50 high-speed trains: the shaft that turns them goes through -significant stress and requires expert tuning. Rolls Royce is the world leader in this field, and quoted £1m for each carrier. Rolls Royce did the work on HMS Queen Elizabeth, but Babcock won the contract for HMS Prince of Wales by quoting around half that. “One bright spark decided he could save half a million pounds,” says someone familiar with the conversations, and Babcock, or its sub-contractor, appears not to have done a good job.

A Babcock spokesperson responded that it “was not part of the sub-alliance that designed and installed the power and propulsion system on the carriers” but did not address the issue of alignment specifically. They added that as part of its contract for maintaining the carriers, in 2023 Babcock “led the team who repaired the propellor shafts”.

Partly because of these issues, the ships have spent less time with the F-35B fighter jets they were designed to carry. But it’s also, I’m told, because the Royal Air Force often refuses to relinquish the aircraft. Unlike in the US, where planes are designated for the navy or the air force at the point of purchase, the RAF and the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm must share them. “And none of the forces are very good at sharing,” says a source. “The RAF are constantly finding things for the F-35 to do, which makes it hard for the Navy to get their hands on them.”

Significantly, sources say, drones were not part of any discussions during the lengthy design and building stages of the ships. The ships can currently only launch a basic reconnaissance drone called the Banshee—but it’s done via a portable ramp, and must drift back down to land or sea by parachute. It’s little more, I’m told, than a training aid.

It wasn’t so long ago that aircraft carriers were considered all-powerful: a portable military headquarters and airbase better protected than most airbases. Right up until the Falklands, a carrier would sit 100 miles offshore and direct operations with impunity. Its jets would be scrambled to combat other jets, while destroyers would create an air defence bubble around it, shooting down any missiles that came their way.

Not that any would: in 1982, the most powerful missile in common use was the Exocet, with a range of around 40 miles. Seven Royal Navy ships were sunk during the Falklands conflict—but not the two carriers. Russia apparently had a long-range missile that could travel 250 miles, but was operationally unproven at the time.

Talk to military strategists and they will invariably compare the carrier to the Queen on a chess board. An all-powerful piece, but one that must be protected at all costs. In recent years, that has become significantly more difficult.

In 2017, the Royal United Services Institute (Rusi)—the UK’s leading defence and security think tank—released a damning report, “Defence Innovation and the UK”. It said Russia and China had developed cheap, long-range missiles that put large western ships at serious risk, focusing many of their efforts on key western assets “that are large, few in number and expensive”. Crucially, it added: “Missiles costing (much) less than half a million pounds a unit could at least disable a British aircraft carrier that costs more than £3bn.”

The carriers, I’m told, were created without a “peer opponent” in mind. It was the age of war far beyond our borders, of Iraq and Afghanistan, disastrous conflicts that nonetheless occurred at arm’s length. “The question was: where do you spend 90 per cent of your time?” someone familiar with the discussions told me.

Reports surfaced last November that British carriers are sunk “in most war games”, with the Royal Navy’s ability to survive “stretched to the limit”. But a military strategist I spoke to pushed back on this: these were full-scale conflict scenarios. In a third world war, they said, most things would be sunk eventually. Talk about hypersonic missiles sinking carriers is essentially talk of a third global war. As one senior figure put it to me: “If Russia or China are trying to sink a Royal Navy carrier, what happens next? There aren’t many holds being barred at that stage.”

The effectiveness of the new breed of hypersonic missiles is also an open question, even among military experts. So far, at least, they don’t seem to be the invulnerable weapon Putin claims. In land-based strikes in Ukraine, they have often been neutralised.

“One of the big lessons is that these missiles can be intercepted,” says Robert Farley, a senior lecturer at the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce and a visiting professor at the US Army War College. “Once you’ve developed the capability of shooting down a bullet with a bullet, shooting down a faster bullet is just a technical problem.”

Yet a Royal Navy strategist I spoke to was less bullish. Yes, they have the capability in theory: the Navy has six Type 45 destroyers, which would accompany the carriers in any conflict and could certainly shoot such missiles down. But these ships were designed in the 1990s, when the fastest missile was not hypersonic but supersonic, travelling at Mach 3 at most. “Once you go faster, you’re putting [the Type 45s] outside their design envelope,” he said, adding: “No one knows how effective anything is until it’s a shooting match.”

Most agree the carriers are surprisingly agile. And oceans are large. Seeing a carrier from a satellite is not the same as hitting one. HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales can travel up to 30mph, and 500 miles a day. Low-tech can sometimes be the best tech. For long-range attacks, they can simply move out of the way. A hypersonic missile, therefore, doesn’t just reduce missile journey time, but increases accuracy.

A missile, broadly speaking, has three phases: boost, to get away from the platform; cruise, to cover most of the distance, and terminal, when it, to use the military term, “prosecutes the target”. During the terminal phase—the last 10 to 50 miles or so, depending on the missile—it can use onboard sensors to alter course. But the outcome is, quite literally, hit and miss.

Most agree that for long-range strikes, a “kill-chain” is required—a series of digital breadcrumbs for the missile to follow. It generally requires a network of low-orbiting satellites to feed the missile live updates: not just where the ship was, but where it will be. Russia, most agree, does not have a kill-chain at sea. China, in the South China Sea at least, likely does.

China began its hypersonic missile -programmes with aircraft carriers in mind. In 1996, during the Taiwan Strait Crisis, the US sailed two carrier strike groups into the straits to force China to back down militarily over Taiwan. China has since become the world-leader in anti-ship missile technology in order to ensure that can’t happen again.

The more important question for the carriers, perhaps, is one of deterrence: are they still the power-projection force they once were? Some argue yes: the carriers could be sent to the Barents Sea, to threaten Russian submarine bases. Others are less convinced.

“There’s no evidence at all that an aircraft carrier [currently] deters anyone from doing anything,” says Professor Peter Robinson, former director of military sciences at Rusi, who says the money spent on the Queen Elizabeth class should have gone on more nuclear submarines. “It hasn’t deterred Russia in any shape or form. It hasn’t deterred Iran. It hasn’t deterred the Houthis in Yemen.”

The Houthi rebels, backed by Iran, -typify the threat carriers are most likely to face at present—and, perhaps, the one that is most concerning. As missile technology advances, it soon won’t just be superpowers that can take pot-shots at carriers. The Houthis even claim to already have a hypersonic missile, the Palestine 2. One missile fired at Israel had “HYPERSONIC” stencilled on the side. (Israel said it was a regular missile with a paintjob.)

US ships have come under direct attack from Houthi missiles in the past year, while last April a Royal Navy Type 45 destroyer intercepted a missile targeting a merchant ship in the Gulf of Aden. It’s a far cry from the days when the US could fly “hunter-killer” Reaper drones over Afghanistan safe in the knowledge nothing could shoot them down.

“The democratisation of these -weapons means that states who possess what were previously very sophisticated capabilities are now handing them out to proxies,” says Robinson. “So you’ve lost the utility of carriers in high-end warfare.”

When I ask if carriers were still at least useful as a form of “soft-power”—a military figurehead, if not the threat they once were—he says, witheringly, “Sure, like the Red Arrows?”

In all the conversations about carriers’ limitations, few people argue they are useless. But all agree: their use cases have become limited. Perhaps more -worrying is the way we see them. A military insider told me that while other nations might view losing a carrier as the cost of doing business—depending, of course, on the business—the UK, as an island nation with a storied seafaring -tradition, would consider it a direct attack on sovereign soil, regardless of whether said sovereign soil was halfway around the world at the time. In this, they’re floating tinderboxes for a third world war.

For proponents of the carriers, the solution is to update, modernise, refit. It would start with strengthening the defensive capabilities of the ships that accompany them. When I visited James Cartlidge, the shadow secretary of defence, at his office in parliament, he was frank about the issues carriers now face.

“I am concerned about ballistic missile threat to the Navy,” he told me plainly, before discussing the Houthi attacks. “This was our own people, our own -sailors in the firing line. What that said to me is that the ballistic threat at sea is evolving rapidly.”

Cartlidge has lobbied strongly for a new missile defence system called Sea Viper Evolution, which would operate from the Type-45 destroyers. Crucially, it can intercept missiles in the terminal phase—important if they’re travelling at hypersonic speeds, as even hypersonic missiles must slow down when they go in for the kill. The upgrades have already begun, but will take a decade to complete.

Even here there’s an irony: the proposal in the 1998 defence review depended on a range of other ships being able to protect the carriers, but subsequent budget cuts have diminished those capabilities. The November announcement of the retirement of the amphibious assault ships HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark—the Royal Navy’s only two warships that can deliver large numbers of troops and equipment to land—was just the latest example.

“It had a good concept,” says Robinson of the review. “It was a balanced fleet. We can protect them: anti-air, anti--missile, anti-submarine capability around it. For the 15 years it took for the carriers to come about, you lost all that protection, you lost amphibious assault, you lost the coherence. We’ve lost all of that in order to fund these two big white elephants.”

A laser defence system called DragonFire, meanwhile, could be fitted to the carriers. But it is still in the testing phase. Once operational, it would be able to take out a drone with a single energy burst for around £10 a time. The cost, it turns out, is crucial. Currently, drones cause the military a headache not because they’re hard to shoot down—they’re much slower than missiles and therefore hitting them is incredibly easy—but because it’s so expensive to do so. Using a missile that costs £1m to hit a drone that costs a few thousand is a bad trade. In military terms, it’s known as “denuding” an opponent’s resources.

Cartlidge believes the timeline is the most important thing. When he was -minister for defence procurement under Rishi Sunak, Cartlidge pushed DragonFire forward from being due to appear in the 2030s to being operational in two years’ time, in 2027.

Partly, this was possible thanks to a new integrated procurement model that Cartlidge announced in February last year. It was an acknowledgement, essentially, that -military development was too slow: that by the time the latest tech had arrived, our adversaries had already made it obsolete. The previous system, the Levene model—implemented after Lord Levene’s 2011 defence reform report—sought to create greater responsibility for military spending from the bottom up by giving individual service chiefs responsibility for their own budgets. The result, however, was widespread over-spend, research programmes that overlapped, and frequent delays in order to balance the books.

The new system, Cartlidge told parliament, would be joined-up and streamlined, and would work more closely with scientists at the government’s Defence Science and Technology Laboratory. It remains to be seen if Labour will make further reforms to the model. The war in Ukraine, Cartlidge tells me, has shown the speed at which technology is changing warfare, and how important it is that the UK isn’t left behind. “No one wanted it to happen, but it is happening, and we should see it as a live test-bed.”

At the start of Russia’s full-scale -invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the battle for the Black Sea was expected to be over before it began. Ukraine only had one warship worthy of the name: the frigate Hetman Sahaidachny, which it scuttled within weeks to prevent it from falling into Russian hands.

Russia had no useable aircraft carrier —the only one it possesses, the -Kuznetsov, belches black smoke and breaks down so frequently it’s often accompanied by -tug-boats. But Russia has an armada of other vessels: battlecruisers, destroyers, frigates, corvettes, landing craft. A navy, in number at least, that is one of the -largest in the world.

At first, it fired ballistic missiles on Ukrainian cities with impunity and blockaded Ukrainian ports. An early Ukrainian scalp—the sinking of the Russian flagship Moskva in April 2022 with Neptune anti-ship missiles, thanks in part to US intelligence on its location—caused Russian vessels to retreat from the Ukrainian coastline, making them much tougher targets without a kill-chain.

The Ukrainian breakthrough came not with the development of missiles, but a sea drone: the Magura V5. Essentially unmanned, armoured speed-boats laden with explosives, they were invented in a Ukrainian garage, and are controlled via satellite communications and a live video link. They could do what few thought possible: travel hundreds of miles across the sea and strike Russian ships directly. The Russian ships retreated entirely from the coastline. Ukraine regained control of the ports. The revolution was remote-controlled.

The Magura drones took out so many Russian ships—around a third of Russia’s Black Sea fleet, according to the Ukrainian Navy—that it has spawned its own meme: “Russia has lost another warship to a -country without a navy, in a land war”.

Yet while the drones clearly represent another threat to carriers, experts I spoke to cautioned against learning too many lessons from Ukraine.

“The Russian navy is kind of a joke,” says Farley. “It’s not an ideal position to protect itself in the first place. They don’t have the sort of the state-of-the-art monitoring and surveillance and defensive systems you would expect of an American, British or French carrier at this point.”

For the UK carriers, Cartlidge believes drones will be a vital factor—ones that could take to the sky from their flight decks. “I’d like us to be the number one uncrewed military,” he says. “If we seize this moment, I think we could lead.”

In May 2023, at a naval conference held in Farnborough, Colonel Phil Kelly, then the Navy’s head of carrier strike and maritime aviation, presented -Project Ark Royal—plans for converting the Queen Elizabeth-class carriers for a drone-based future. “The question is not if the Naval force will prioritise and leverage uncrewed -platforms and systems,” Kelly told the audience, but “how quickly and -efficiently” it could be done.

Multiple smaller ramps, he demonstrated, could be added in order to launch drones. Along with light reconnaissance drones, they would be able to launch a UK attack drone currently in development known as Vixen. Like all such drones, Vixen could be piloted from afar. But it could also perform as a “loyal wingman”—flying alongside a F-35 fighter, partly controlled by AI, partly by the pilot.

Announcing funding for the prototype in 2021, the government said Vixen would be armed with missiles and surveillance equipment, and would be the UK’s first uncrewed platform “able to target and shoot down enemy aircraft and survive against surface to air missiles”.

Yet Vixen, for now, remains unfunded beyond its prototype, with the late 2030s seen as its earliest arrival date. Project Ark Royal, meanwhile, is still just an idea—one currently being debated as part of the government decision on the carriers. One thing is certain: it wouldn’t be cheap. For Vixen to take off from a Queen Elizabeth carrier, it would require retrofitting one or both with a catapult after all: a U-turn on the U-turn on the U-turn.

We would also still be lagging behind our rivals. Turkey, for instance, already has a drone-only carrier: TCG Anadolu.

There may even, I’m told, be pushback from the RAF. Over a decade ago, in 2012 and 2014, the UK and France signed agreements to develop a drone together, dubbed the Future Combat Air System, but the joint programme was eventually cancelled due to objections from the RAF. France signed a deal with Germany instead, with Spain joining them later.

“The RAF killed it,” says a source familiar with the discussions. “They claimed it was because we’d spent a couple of hundred million [on it]. But I think the RAF didn’t want to do it because the RAF without pilots isn’t really a force,” they say, joking: “You don’t pick up many girls in bars by saying you sit in a portacabin shooting people in Afghanistan.” But, they add, “This is how the services really do affect decision-making. There’s a lot of people invested in the status quo.”

The last commanding officers of the Queen Elizabeth carriers are unlikely to have yet been born. Each vessel has a stated lifespan of 50 years. Of course, after the strategic defence review this spring, that might be significantly reduced. Despite their -limitations, many are incredulous that the government could ditch both vessels after spending £6bn on them.

“The amount of money we’ve spent in order to mothball it will be unbelievable,” one senior source tells me. “And I can’t understand how Labour could possibly argue the case.”

“The fundamental benefit of an -aircraft carrier has not gone away,” says Cartlidge, “the ability to have that landing deck out at sea. We should seriously look at the idea of the hybrid carrier that still can carry its F-35Bs, but really lean into the potential for carrying a significant drone force. I don’t think we should start writing off these extraordinary platforms just yet.”

It’s estimated that the savings for mothballing both would amount to around £200m a year—a small amount, considering the cost of these vessels. Yet updating them for an era of drone warfare could cost significantly more. It comes down, some argue, to a surprisingly simple choice: do we double-down on these carriers’ future, or relegate them to the past? Others say the present has already made them obsolete.

Last December, Ukraine did what few could have thought possible at the start of the war. It launched a carrier strike. It was, in many ways, the classic use of an aircraft carrier. A ship sailed hundreds of miles across the Black Sea. Once in range of the gas platforms that were the target, its fighters took off on a bombing raid. The only difference between this and the carrier attacks of the past: the ship was a modified Magura V5 drone carrying aerial drones. The Russian-controlled platform burned. The carrier, as yet unnamed, was around six metres long.