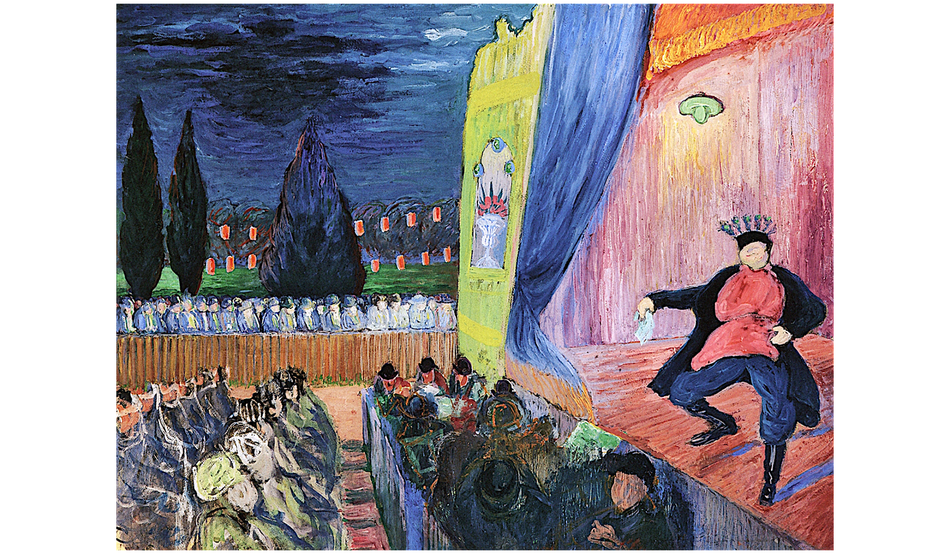

It’s cruel to look at Summer Stage (1910) when the English weather can’t make its mind up. What a treat to imagine being sat, lightly bundled in Bavarian glad rags, under a swollen summer sky. For that is what the foreground of this painting offers: rows of theatregoers, lit jointly by moonlight and the hot glare of a stage.

In the style of many a fated romance, I first saw this painting across a crowded room at the Tate Modern. It was August then, and my climatic envy was inversed: a friend and I had sought out the gallery’s Expressionism show as refuge from a pantingly hot day. What drew me immediately to this one work was the sky: its eddying blues, a chromatic extension of the stage’s curtain, seemed discordantly sea-like. It remains my favourite part of the painting; every glance yields a new tint.

I had heard of the artist Marianne von Werefkin before. She was hazily committed to my mind as German Expressionism’s darling, the enigmatic matriarch of the Blue Rider. What I did not know, but am now most glad to, is that she was descended from a lofty line of Cossack princes and drew her first breaths in the Russian palace of Tula. Her childhood studio—no lapse in splendour here—was in the gilded breast of the Peter and Paul Fortress in St Petersburg. It was not until her thirties that she moved to Munich, where she established her Pink Salon, made a name for herself and lurched headlong into the city’s full-bodied performance scene.

Swilling around von Werefkin’s salon was Alexander Sacharoff, eyebrow-raiser par excellence, whose crossdressing dance shows scandalised Munich in the 1910s. We do not know exactly when von Werefkin met Sacharoff, or how. What we do know is that it must have been some time before Sacharoff’s famous debut at the Munich Concert Hall, in which he appeared draped in Renaissance silks, a blazing, barefoot embodiment of what one morning paper would call “womanish sensitivity and sexual perversity”. Von Werefkin’s The Dancer, Alexander Sacharoff, in which her sitter is coyly garbed as Salome, was painted months before, in 1909.

Is the performer in Summer Stage also Sacharoff? I think not. But there is an analogous indeterminacy to the figure: a facelessness, common to all the painting’s inhabitants, not to mention a bodily ambiguity. We can’t be sure of the performer’s gender, but that is precisely the point. Their billowing shirt, cinched by a thin slash of white paint, gives the tentative illusion of breasts. Stomping in defiance is a classically male boot. Visually, performer and stage are portioned into that most basic of gender binaries: pink and blue.

Throughout her time in Munich, von Werefkin patronised performances interested in crossdressing, in gendered play. She, like the artform, was committed to resisting categorisation: “I am not a man, I am not a woman, I am I”, a diary entry declares.

Though, curiously, the performer is not our painting’s uncontested protagonist—nor, in fact, is its titular stage. Both are restricted to the lurid right-hand slice of canvas. Look at the lines of figures; the trees; the sky I like so much. They are included for a reason. They, themselves, are theatrical: the people choreographed minutely; the landscape like a sensational set.

The spectators sat with their backs to the trees give us that most precious of things: a glimpse of the artist’s own point of view. Sat on the opposite side of the stage from von Werefkin, their seats are a direct reflection of hers. Blank of face and muted of wardrobe, any one of them could function as her mirror image. As we gaze at them, we vicariously take the artist’s place, enjoying this night at the theatre just like she did.