When the charcoal-edged eyes of Annie Sprinkle first met mine, I was unsure where to look. Clad in leather lingerie, the prostitute-turned-porn star doesn’t really care where you direct your bashful gaze—as long as it’s towards her. After all, she is a performer, and you’re here to see the show.

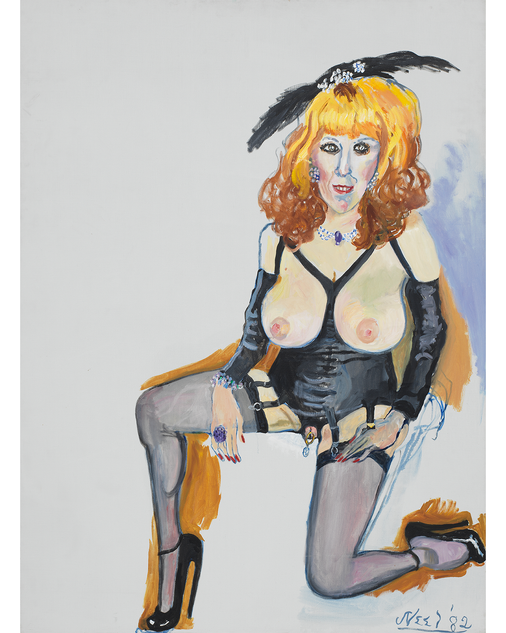

In the new exhibition At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World at London’s Victoria Miro gallery, we see the portrait of Annie Sprinkle by the American painter Alice Neel (1900–1984) take centre stage. In Neel’s work, Sprinkle kneels before you draped in diamonds, a towering stiletto anchored to the floor. Her breasts and pierced vulva are on full display, but her relaxed posture—arms gently resting on her thighs, a coquettish grin—leaves no trace of vulnerability. The painting is signature Neel: a simple composition paired with loose, expressive brushstrokes that invite Sprinkle’s outsized character to fill the frame, allowing the viewer to finish the story.

A portrait of a porn star in fetish gear might have furrowed many a brow in the early 1980s, but not Neel’s. The painter delighted in subversion, devoting much of her career to speaking out against injustice and capturing those marginalised by dint of their class, race or sexuality, insisting on their recognition in the halls of history.

Her portraits of sexual and gender minorities in the 1970s and 1980s documented communities caught in a moment of rapid flux. It was a time of growing visibility but also of mounting discrimination—queer people often faced job losses, housing insecurity and social exile if outed. In places like Greenwich Village—where Neel had once lived—LGBT+ communities sought both refuge and resistance, carving out clandestine spaces in a city that was both their home and, as per the Stonewall riots, their battleground.

Curated by Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Hilton Als, At Home illuminates Neel’s profound connection with queer subjects, portraying them with both intimacy and immediacy. Als has long admired Neel’s instinct for capturing human complexity and vulnerability—how she gravitated towards outsiders and, with unflinching honesty, peeled back their masks to reveal whatever cracks lay beneath.

“When she died in 1984,” he writes in the catalogue essay, “Neel had a great number of masterpieces to her credit, a galaxy of masterpieces, I would say, that bear witness to the terror we usually run away from, having no language for it—namely alienation, disconnection, love.”

True, Neel left a formidable body of work, but At Home is more of a dwarf galaxy; with only 17 paintings, dating from 1932 to 1983, spread across two expansive rooms at Victoria Miro, some feel swallowed by the whitewashed space. Still, several works exert their own gravitational pull—a testament to Neel’s command of line and colour, deliberate distortions and keen psychological acumen. “Like Chekhov, I am a collector of souls,” Neel once said. “If I hadn’t been an artist, I could have been a psychiatrist.”

Neel’s journey to becoming a “collector of souls” was paved with bumps and thumps. Born into a straightlaced Pennsylvania family in 1900, she studied at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women before marrying the Cuban communist José Enríquez and moving to Havana. There, she experienced great love—and even greater loss. Her first daughter died of diphtheria in 1927 and, shortly after, Enríquez abandoned her, taking their surviving child, Isabetta, with him. Neel suffered a breakdown, attempted suicide and was institutionalised. During this dark period, art became her salvation, as she turned to themes of motherhood and loss while cultivating her frenetic, distortive style of portraiture.

After eventually relocating to Spanish Harlem with two young sons from two different fathers, Neel focused on painting immigrants and working-class mothers—capturing the warts-and-all realities of motherhood long before it became a feminist cause célèbre. By the early 1970s, as the Women’s Liberation Movement gained traction, Neel—long used to painting in obscurity—was suddenly in demand. Time magazine even commissioned her to paint feminist writer Kate Millett in 1970; Neel’s own copy of the magazine appears in a vitrine upstairs at the At Home exhibition.

Neel—long used to painting in obscurity—was suddenly in demand

For much of her career, Neel’s figurative style had been dismissed, overshadowed by the swirls and splatters of Abstract Expressionism. Yet she persisted. Her struggles—poverty, loss, heartbreak, artistic rejection—deepened her empathy for the underdogs. “I love people under all kinds of stresses,” she once said. “I am a psychological painter because life does a lot of things to people.”

Life had done, and would do, many cruel things to Neel’s queer sitters. One of the most affecting aspects of At Home is the knowledge that many of the individuals she painted would later become victims of the looming HIV/AIDS crisis. One example is the artist Brian Buczak (painted in 1983), who died from AIDS-related complications years after sitting for Neel and whose portrait hangs just above the reception at Victoria Miro, setting the exhibition’s empathetic tone.

This relatively sparse show is an iteration of a more extensive exhibition curated by Als at David Zwirner Los Angeles earlier this year and a sequel to his 2017 show Alice Neel: Uptown, which focused on her Spanish Harlem portraits. Here, Als presents individuals who were considered “queer” not only in terms of their sexuality, but also theorists, activists and politicians who would qualify as “queer” due to their singular perspectives within their respective fields. “They reflect Alice’s own interest and commitment to difference,” says Als.

Among the sitters on view are writers, performers, and poets including Frank O’Hara (1960) and Allen Ginsberg (1966). Notably absent are works such as her portrait of New York mayor Ed Koch—a closeted gay man who presided over the city’s catastrophic response to the AIDS epidemic—and her strikingly vulnerable depiction of Andy Warhol, his chest scarred from his near-fatal shooting. Instead, a rather wonderful preparatory ink sketch of Warhol’s head is displayed upstairs, a snapshot of the fragility beneath the stiff silver wig of the pop artist.

At Home is dominated by the arresting portraits of Annie Sprinkle (1982), the fine-art framer Dennis Florio (1978), a ballet dancer (1950) and Kris Kirsten (1971)—all hung on the ground level. Neel is at her best when she frames the body’s contours with blues and blacks, as in these works, animating flesh and form with a sizzling vitality. “I want to catch life as it goes by,” she once said, “hot off the griddle.”

But what often stands out most in these portraits is the eyes—bulbous, longing, often slightly asymmetrical. Whether it’s the cartoonishly large eyes of Adrienne Rich (1973), the glittering gaze of Annie Sprinkle or the soft, almost plaintive stare of Dennis Florio, they seem to beckon the viewer, demanding, in turn, to be seen. Perhaps Neel painted such large eyes because she needed them wide enough for her to dive in—and collect the souls behind them.

“She seemed very queer to me,” Sprinkle later recalled of her time as Neel’s sitter, “…her curiosity.” This curiosity made Neel a chronicler of those living on the margins of 21st-century America. At a time when LGBT+ rights are under renewed attack in the States, At Home stands testament to an artist’s ability to affirm, dignify and immortalise. If it teaches anything, it’s that her queer eye is one we should all strive to see life through.

At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World is on at London’s Victoria Miro gallery until 8th March 2025