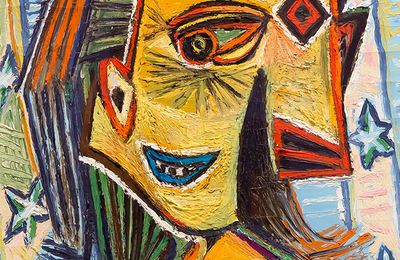

Pablo Picasso: the patriarch of modern western art. The archetypical genius. The man who pushed the limits of form in ways that few others had done before, or since. An artist whose ascent to greatness seemed all but inevitable from the day he was born, judging by the sketches of animals, completed at the age of seven or even five, that often appear at the start of exhibitions of his work—of which there remain many, year after year, and at any given time. He was the artist who was more than just an artist: if James Joyce wrote the scripture of modernity, then it was Picasso who provided its icons. Enduring, universally adored, transcendent: these are the only kind of words we can use to adequately describe him and his work.

At least, that’s the case if you believe the usual spiel written about Picasso, which remained largely unchanged for a long time. By questioning his lasting influence, you risked sounding like somebody who didn’t understand art. It was like asking if Jesus Christ had any lasting influence on Christianity: art was Picasso, and Picasso was art, and it was as simple as that.

Today, on the 50th anniversary of his death, you could say we’re a little more agnostic. Fifty years is a long time to comb over the facts of a person’s life, which for Picasso always meant far more than any individual work he created. “It’s not what the artist does that counts,” he once said, “but what he is.”

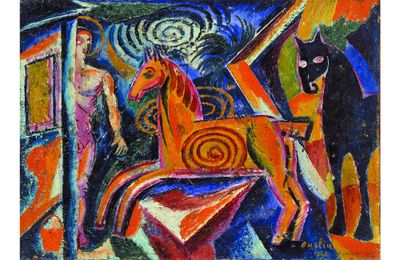

And what Picasso is—or was—was indeed far more than just an artist. He was also a man who treated people badly, women most of all, whom he saw as either “goddesses or doormats” to be cheated on or abandoned or objectified. When, at the age of 45, he met the 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter and told her that “you and I are going to do great things together”, she probably didn’t expect to see half her face and arm shaped like a penis in one of his paintings. To this abject behaviour (which is only the tip of the iceberg) we might add a troubling appropriation of African art and artefacts and even—what with his obsession with bullfighting—indifference to the suffering of animals.

Yet if it feels easier to draw conclusions about Picasso the man, it seems much harder to pin down his most lasting impact on art itself. This is a question many of us will be thinking about at any one of the many exhibitions and jamborees planned across the world this year to mark the anniversary.

Among those shows is one at La Casa Encendida in Madrid, called Picasso: Untitled, opening 19th May. Here, 50 works from Picasso’s ambiguously defined “late period” are to be exhibited, with each piece given a new title by one of 50 contemporary artists. The idea is to create a dialogue for “the kind of difficult conversations that we have been having regarding power, gender and race that have appeared in the last 50 years since Picasso’s death,” the show’s curator, Eva Franch i Gilabert, tells me over a Zoom call from Barcelona.

Picasso was apparently never that interested in titling his artworks, leaving the job mostly to friends and curators. “There is very little tradition of artists naming their paintings before the 20th century,” says Franch, with Picasso himself generally continuing that tradition. “It is a phenomenon of the salons… In a certain way, titles are a product of a business model, but also of the democratisation of access to art.”

“All his work is autobiographical,” chimes in Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, also on the call and, as the name suggests, Picasso’s grandson; the show at La Casa Encendida is in collaboration with his foundation. “Including dates was more important for him as a kind of memory of where he was” at the time he was painting, he continues. (Once again with Picasso, the centrality of the artist comes before what the artist creates.)

When I ask Franch what kinds of conversations the exhibition hopes to open up about Picasso—with artists as diverse as Camille Henrot and Erwin Wurm on the list of 50—I can’t help but feel her answer comes over a little vague. “Some of the responses are hilarious and humorous and poetic,” she says, “some of them are political and with very strong edges.” That’s all well and good, but if Picasso always left the job of titling his works to others, who’s to say that the titles weren’t hilarious, poetic or political before?

Likewise, I’m not entirely convinced when I ask what they think is Picasso’s most lasting influence on contemporary art. For Franch, it was his way taking inspiration from and showing respect for those before him—“when you look into many of his works, you’ll see he’s looking to Manet or into others to try to learn from them”—and also his interest in depicting homeless people, prostitutes and “and all other different kinds of figures in society.” For Ruiz-Picasso, the answer is much more existential: it’s found in how Picasso and other artists of that time “just liberated our free thinking”. “Now you can tell a police officer that you are an artist,” he says. “You don’t go to jail immediately.” Yet those are all things you could plausibly attribute to other artists throughout history. What kind of people were painted by Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gaugin and Johannes Vermeer and others, if they weren’t ordinary? And is society’s liberal permissiveness towards art a direct consequence of that art, or of wider political attitudes?

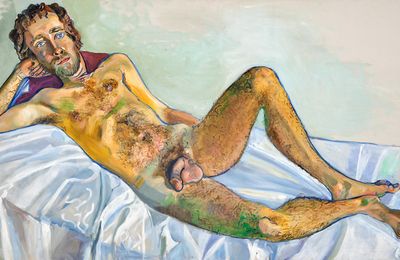

I ask Ruiz-Picasso if there is anything he personally finds problematic about Picasso today, or whether—the old cliché—it’s possible to separate the art from the artist. “Of course, Picasso was a man and he had a different life,” he says. “But in my opinion he was not keeping anyone captive or prisoner, the women he was with. And most of the people who knew him, who are still alive—there are not many—were so encouraged in their own creativity.” He goes further in praising his grandfather, by saying he was “better than most human beings. He got naked in front of everyone in paint, where his life had no censorship.”

It feels as though the more we try to interrogate Picasso and his work, the less explicable it becomes. Yet, perhaps, that’s exactly what he would have hoped for. “I can hardly understand the importance given to the word ‘research’ in connection with modern painting,” he said in 1923. “In my opinion to search means nothing in painting. To find is the thing.” And it’s true that, in spite of everything we might know about Picasso—in spite of all the prior research we do—when we are left alone before his work there remains something we cannot place, yet which draws us in all the same. We’re still left with that desire to find something, without knowing exactly what it could be. “What Picasso is, apart from what he does, is indeed remarkable”, as John Berger wrote in Success and Failure of Picasso; “and perhaps all the more so for being indefinable.”

It might be that Picasso’s ultimate legacy will in fact have nothing to do with his art, but the extent to which he embodied the age he lived in. The 20th century was a time when art became seen as the unbridled product of individual creative expression—the artist’s “genius” and “vision” freed from both burdensome collaboration in the workshop and prudish aesthetic tastemakers in the academy. It was also a time when the commodification of art really took hold, leading to the eyewatering prices we see at auctions today. Perhaps it is in Picasso, who put himself front and centre of his work while also making millions from it, that these two trends converged. The question for artists working today, then, is not if they are inspired—or outraged—when standing in front of Guernica or Picasso’s weeping women. It’s whether that 20th-century way of thinking about art is still relevant today—or if it’s about time that we tried, just like our predecessors before us, to do things differently.