When Putin’s tanks rolled across the Ukrainian border on 24th February 2022, the new government in Berlin immediately felt the shock. Germany is Europe’s industrial powerhouse and was its biggest buyer of Russian gas and oil—energy imports that not only kept households warm but fuelled the industries behind its economic success. As it became clear that this was, indeed, a full-scale war, two questions came to the fore: how had Germany become so dangerously dependent on Russian energy and how could it get out of it? Less than a year later Olaf Scholz, Germany’s chancellor, declared the second question resolved. The first continues to reverberate through the country’s fractious domestic politics.

Energy politics have long been fiercely debated in Germany. In the early 1970s the word energiewende, or energy transition, denoted the phaseout of nuclear power championed by Germany’s vocal anti-nuclear movement. In 1979, the Social Democrat Party (SPD) in the Schleswig-Holstein region adopted the phrase to describe a combined policy of nuclear phaseout, energy efficiency and a reduction of imported oil. After the Fukushima disaster in 2011, chancellor Angela Merkel committed to shutting down nuclear plants and to a low-carbon transition that would also end coal use.

Today, energiewende is the foundation of an increasingly ambitious climate policy that aims at a future transition to renewable energy. But in February 2022, as today, fossil fuels were the bedrock of German energy; 34 per cent of the country’s oil and around 55 per cent of its gas came from Russia. As the war unfolded, it became clear that the means of their delivery was as critical to Germany’s dependency as the source: gas was arriving in Germany almost exclusively by pipeline. The story of those pipelines is the story of Germany’s political, security and energy entanglement with Russia.

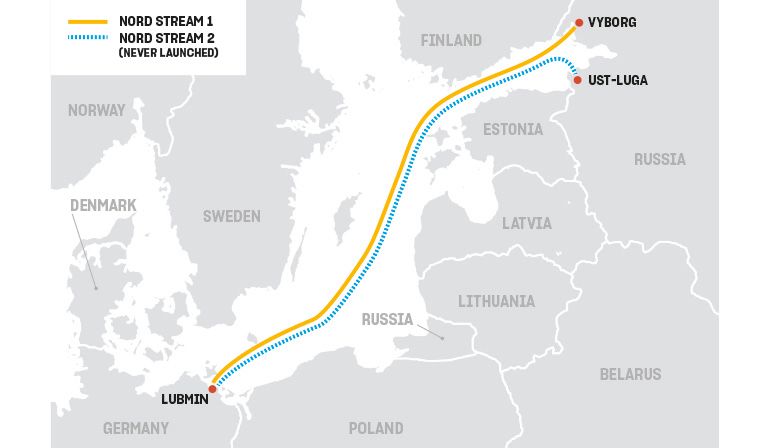

On 8th November 2011, Angela Merkel and Dmitry Medvedev, then Russian president, jointly turned a wheel in the small northeastern German town of Lubmin, opening the flow of gas along a newly built pipeline that ran over 1,200km under the Baltic Sea from Vyborg near St Petersburg. That turn of the wheel completed a project that had begun in 2005 in a deal struck between the former SPD chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, and the man who both preceded and succeeded Medvedev as prime minister: Vladimir Putin. The pipeline was Nord Stream 1, and when Schröder left office shortly after the deal was done, he went, at Putin’s invitation, straight to a board position with Nord Stream AG, the company that would operate it.

Until Merkel and Medvedev met in Lubmin, Russian gas had reached Europe through a network of Soviet-era pipelines, several of which crossed Poland and Ukraine. Both countries opposed Nord Stream, fearing it would allow Putin to reroute energy away from their pipelines, depriving them of valuable transit fees and enabling Russia to cut Ukraine’s supplies without affecting the EU. In 2006, Radosław Sikorski, then Poland’s outspoken minister of defence, compared Nord Stream 1 to the 1939 Molotov--Ribbentrop non--aggression pact between Stalin and Hitler that had paved the way for Germany to invade Poland. The fears of both Kyiv and Warsaw were well founded: in -winter 2009, Russia cut off gas supplies to Ukraine, while Poland found itself in dispute with the Russian gas company Gazprom over pricing.

There were concerns in Brussels too, as Hanne May of the German Energy Agency explains: “People saw all their worst fears about Ukraine coming true. Sweden, Finland, Denmark, the Baltic states, Poland all opposed it. Gazprom spent a fortune on public relations to get acceptance for it.” Some environmental groups tried to hold up construction to protect herring that spawn in the western Baltic; others objected on climate grounds. But for Merkel, the pipeline heralded a “safe, sustainable partnership with Russia in the future”. With Russia as a major supplier for decades to come—as she told the 400 guests at the opening ceremony, who included the French and Dutch prime ministers—“the purchasing countries and Russia are profiting in equal measure.”

In Germany, the idea that physical infrastructure would bring mutual benefits had deep historical roots. Andreas Kraemer, founder of the Ecologic Institute thinktank in Berlin, traces its origins back to Ostpolitik, the signature policy of Willy Brandt, the SPD chancellor of West Germany from 1969 to 1974. “At the time, there were nuclear weapons on both sides, and both sides adhered to the Mutually Assured Destruction strategy,” says Kraemer. “Brandt looked for engagement with eastern Europe, rather than the confrontation favoured by previous Christian Democrat administrations. He believed that better relations and trade would eventually undermine the communist regime in East Germany.”

Kraemer says that Ostpolitik also reflected a mutual cultural respect. “Russia and Germany regard themselves and each other as the only significant land-based empires in Europe, civilisations with deep foundations in culture, in art, literature, music. They don’t see other, smaller European countries as on the same level. Hitler regarded Asians as Untermensch, rather as Putin regards the Ukrainians. It pains me as a German to describe this, but it’s real.”

Energy analyst Pieter de Pous, from the thinktank E3G, also sees Ostpolitik as the gateway for the pipeline. Just a year after it was announced in 1969, the first pipeline contract was signed between Russia and West Germany and four decades of construction began. “Domestic coal had been in decline since the 1950s,” says de Pous. “Pipelines that delivered gas from the field directly into a huge BASF [multinational chemicals giant] plant on the Rhine… who would say no to that?”

The project had become a liability that was damaging Germany’s relationships with both Brussels and Washington

Germany paid for the infrastructure and in return received a steady supply of cheap gas under long-term contracts. Advocates believed the arrangement would bring peace and security. “The Russians were seen as berechenbar—reliable, predictable, good partners. We knew them. They honoured the contracts, even through the collapse of the USSR and everything that followed,” says Kraemer. “We were so convinced we knew them,” he adds, “that we failed to notice how much Putin was changing Russia.”

As Putin annexed Crimea in 2014, Germany seemed unconcerned about its dependency. While the EU was installing reverse flow technology in its pipelines to ensure that Poland could be provided with Norwegian gas if Russia cut off its supply, Germany was planning a second Baltic pipeline.

The key figure was (once again) Gerhard Schröder, a man who had called Putin a “flawless democrat” in 2004 and had become a leading figure in a pro-Russian and anti-Nato wing of the SPD. Schröder had headed the shareholder’s committee of Nord Stream 1 and in 2009 joined the board of TNK-BP, a joint venture between BP and Russian partners. By 2016 he had a post with Nord Stream 2—the planned second pipeline—and the following year he was earning $350,000 a year as a board member of the Russian oil company Rosneft, which was already under sanctions over Ukraine.

Schröder promoted Nord Stream 2 against growing opposition both within Europe and from the US. In 2017 the vice president of the European Commission, Maroš Šefčovič, tried to take over Germany’s negotiations with Russia about Nord Stream 2, arguing that the project ran counter to the bloc’s energy and foreign policy goals. Meanwhile, in the United States that same year, the Senate passed a sanctions law which, under the heading “Ukranian [sic] Energy Security”, committed the US to “continue to oppose the Nord Stream 2 pipeline given its detrimental impacts on the European Union’s energy security, gas market development in Central and Eastern Europe, and energy reforms in Ukraine.”

Gazprom provided half of the €9.5bn finance for the pipeline, with the remaining funds coming from German energy companies Wintershall (a subsidiary of BASF) and Uniper, along with Shell, the French energy conglomerate Engie and the Austrian company OMV. The gas was to be drawn from the huge reserves in the Yamal Peninsula in Russia and make landfall, as the first pipeline did, in Lubmin.

By 2020 construction was largely completed, but the project had become a political liability that was damaging Germany’s relationships with both Brussels and Washington. As critics pointed out, it was surplus to Germany’s present and future requirements.

In May 2021, a group of European and US politicians, diplomats, researchers and civil society representatives appealed to the German government to impose a moratorium on Nord Stream 2. Among other objections, they pointed out that as the biggest fossil fuel infrastructure project in Europe, the new pipeline would lock in gas imports for decades, just as the EU and Germany needed urgently to reduce gas use to meet their climate goals.

Besides, they argued, the strategic hopes of “Wandel durch Handel” (change through trade) had failed. Russia had launched attacks on Ukraine and on western democracies, including several targeted poisonings on British soil, most notoriously the attack on Sergei and Yulia Skripal in Salisbury in 2018. Both Barack Obama and Donald Trump had expressed opposition to the project, and in December 2019 a new set of sanctions on companies working on Nord Stream 2 was included in the US National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

“The problem was that we had already invested billions of euros, and many people thought it was crazy not to finish it,” says May, of the German Energy Agency. Among this category was Manuela Schwesig, the SPD prime minister of the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, home of the German end of the pipeline. Schwesig made it her business to ensure that sanctions would not prevent the completion of Nord Stream 2. Insisting the pipeline was a private project with no political implications, Schwesig set up an NGO called the Climate and Environmental Protection Foundation in 2021.

“It was not a good idea to call it a climate foundation,” says May. “It was an entity devised to finish building the pipeline.” The foundation did plant some trees, but its main purpose was to deploy the €20m donated to its coffers by Nord Stream 2 to shield those companies involved in the construction from US sanctions. The climate foundation set up its own company to channel funds and buy materials and equipment, including a ship. According to the foundation’s June 2022 annual report, the company also concluded contracts worth €165m with some 80 unnamed companies.

These efforts bore fruit. Gazprom announced in September 2021 that construction was complete, and gas could begin to flow the next month. For the pipeline’s opponents, the only remaining prospect of halting it lay in blocking its permits. That had seemed an unpromising option, but by then Germany was on the cusp of political change.

In September 2021, just as Nord Stream 2 was completed, Germany plunged into its first federal elections in 16 years in which Angela Merkel was not a candidate. There were three possible successors for the post of chancellor: Annalena Baerbock of the Green party, Armin Laschet of Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Olaf Scholz of the SPD.

Climate change was a key election issue, in part because Germany had suffered devastating flooding two months before. As the results came in, the CDU had lost heavily, the Greens had scored their best result ever and the SPD had won a slight lead. On 24th November, after months of negotiation—and for the first time in Germany’s history—the SPD, the Greens and the free-market liberal FDP agreed to form what is popularly called the “traffic light coalition”.

From this agreement it was Scholz—a cautious SPD figure who had worked closely with Merkel as both vice chancellor and finance minister under his party’s “grand coalition” with the CDU—who became chancellor; Robert Habeck, co-leader of the Greens, took over a new super-ministry for economy and climate, giving him a uniquely powerful platform from which to push for radical climate action; his colleague Baerbock became foreign minister, leaving the FDP’s Christian Lindner to take up the position of federal finance minister.

Germany’s new federal government was sworn in on 8th December 2021, and as the new year dawned was drawing up ambitious plans, including to bring forward the country’s exit from coal to 2030 (from 2038) and reach 80 per cent renewable energy by 2030 and climate neutrality by 2045, five years ahead of the target in the Paris agreement. Freshly appointed ministers were instructed to accelerate the decarbonisation of transport, buildings and agriculture. In his first government statement, Scholz promised the “greatest transformation of our industry and economy for at least 100 years”.

The permits for Nord Stream 2, meanwhile, had stalled. Germany’s gas and electricity regulator had suspended certification on the grounds that Nord Stream 2 was not a German legal entity, obliging the company to create a German subsidiary. It also needed approval from the European Commission, which insisted that the operator of the pipeline and the supplier of the gas be distinct entities to comply with EU law.

Then, on 21st February 2022, Putin announced in phone calls to both Emmanuel Macron and Scholz that he would recognise the “independence and sovereignty” of the breakaway statelets of Donetsk and Luhansk in eastern Ukraine. This was followed by a rambling television address in which Putin described Ukraine as an integral part of Russia with no tradition of statehood of its own.

The next day, Scholz announced he had ordered the withdrawal of the pipeline’s supply security report, without which Nord Stream 2 couldn’t begin delivering gas. Asked whether the pipeline would ever start operating, Scholz told the German broadcaster ARD that: “We are now in a situation where nobody should bet on it.”

Government officials made frantic calls and held emergency meetings, as ministers cleared their diaries and began to plan for the worst. From Brussels, on the 21st, Baerbock and her French counterpart Jean-Yves Le Drian both telephoned the Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov. “It was a crazy phone call, our last. After that I knew it wouldn’t work anymore,” Baerbock told Stern magazine later.

The day after, she phoned Germany’s parliamentary group leaders to tell them that war seemed imminent and ordered Germany’s embassy in Kyiv to evacuate; Habeck was given a dossier by US embassy officials that detailed Russia’s preparations: “The blood supplies are thawed, the rocket launchers are loaded, the vehicles are marked, and the troops are clearly moving towards the border,” it said. The following day, Russia invaded Ukraine.

Few expected Ukraine to resist for long. Had Volodymyr Zelensky gone, “It would have been over. Germany, Italy, France would have rolled over and moved on,” says de Pous. But Zelensky stayed, and in the aftermath of the invasion, Germany began a wrenching break with the near-pacifist policy that had dominated its politics since 1945.

Scholz spoke of a “turning point” for Germany, announcing support for Ukraine and a special fund of €100bn for the German armed forces. More than 100,000 people took to the streets in Berlin to express their anger at Russia, while the political class debated what kind of military support they could give.

There were other urgent questions, too: more than 80 per cent of domestic heating demand was met with mostly imported fossil fuels. The coalition agreement had pledged that by 2025 all newly installed systems would have to run on 65 per cent renewable energy—a target that was quickly advanced to 2024. But the most immediate problem was how to endure the coming months and refill gas reserves for the following winter.

The government faced four simultaneous challenges: how to disconnect from Russian energy supplies, how to honour its green commitments, how to keep the wheels of industry turning and how to stave off a householder rebellion over soaring energy prices.

Robert Habeck had no illusions about the scale of the task. After taking office, he had asked for an assessment of Germany’s dependence on Russian gas and replaced most of the senior officials in his ministry, determined to reverse what he saw as years of pro-Russian policy. After the invasion, he asked his ministry to bring forward a report on the country’s energy transition from 2026 to the summer of 2022, to model how Germany could boost its roll-out of renewables and expand its electricity grid, and investigate the potential for an early end to the use of coal-fired power plants, in 2030.

Habeck’s plan was to increase the share of renewable energy in the heating sector and make faster progress on existing energy efficiency goals, hoping that this would help Germany stay aligned with climate targets while keeping heating bills manageable. But first he had a crisis to deal with, as Germany’s closest energy partnership, the foundation of its postwar economy and its industrial success, began to unravel.

Gas was still flowing through Nord Stream 1, but for how long? If Russia was prepared to sacrifice the revenue, that too could stop overnight. “Russia had been clear that they saw [gas] as a potential weapon. They had started using it in the summer of 2021… using supply to nibble at prices and put pressure on the EU in preparation for the invasion,” says de Pous.

Gazprom also owned the biggest gas storage facility in Germany, which was suspiciously low on stocks. Before the invasion, on 19th February 2022, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen had told the Munich Security Conference there were clear signs that Russia was preparing to weaponise its control of supply. Gazprom was deliberately constricting deliveries, odd behaviour at a moment when prices and demand were skyrocketing. That April, Germany took over Gazprom’s German assets, including the storage facility, after a mysterious transfer of ownership to a hitherto unknown Moscow company that violated German regulations.

There was also the problem of Russian ownership in the oil sector: Rosneft held a majority share in a large refinery in Schwedt, at the end of the Druzhba pipeline, which only refined Russian oil. It processed about 220,000 barrels of crude oil a day and supplied about 90 per cent of Berlin’s transport fuel, as well as supporting 1,200 local jobs. Because of the pipeline policy, Germany’s ports had not developed the capacity to handle oil supertankers that could carry the fuel if the refinery in Schwedt stopped working.

Habeck set about securing new supplies. He visited Poland to ask for the use of the port of Gdansk for oil supertankers. The Polish government agreed, but on one condition: that Germany nationalise the Schwedt refinery. For the time being, Habeck had no legal means of doing so. Simultaneously, he began scouring the market for supplies of liquid natural gas (LNG), while appealing to German households and industry to reduce their demand. “He bought all the LNG available,” says energy journalist Malte Kreutzfeldt. “There were no long-term contracts, so the prices were crazy high for a few months, from five cents a kilowatt an hour to 50. We took LNG that was destined for others, like Pakistan.”

By April, Habeck had reached an LNG supply agreement with Qatar, but he didn’t have any way to get it into Germany. Unlike other EU member states, most of which also had some degree of dependence on Russian gas, Germany’s history of cheap and secure pipelines meant it had no LNG terminals where boats could unload. Just a year earlier, Uniper had dropped plans for an import terminal in Wilhelmshaven, on Germany’s North Sea coast, citing lack of interest. Another, planned for the town of Brunsbüttel in Schleswig-Holstein, was not expected to be completed until 2026, if at all. Now, even the fiscal hawks of the coalition’s FDP were advocating for German terminals, but the country’s construction record was not encouraging: permitting was slow and cumbersome, and environmental activists were likely to fight construction in court.

There was one possible option: floating terminals that could be in operation within weeks. Habeck’s officials reported that there were 48 such terminals in the world, owned by two companies, one Norwegian, the other Greek. Five were available; Habeck urgently needed four. In March, on a trip to Oslo, he secured both increased supplies of Norwegian gas and the promise of a 10-year lease on two floating terminals. A similar offer was accepted by the Greek company and Habeck later sourced a fifth.

The deals helped, but other measures would be needed. Nord Stream 1 could carry 55bn cubic metres of gas a year while one floating terminal held only five billion. The difference would have to be imported by Germany from its neighbours until it could build its own terminals. The government relaxed environmental regulations, provoking a predictable outcry from members of Habeck’s Green party, who complained that the floating terminals put porpoises at risk. Habeck was unimpressed.

The effect of this crisis on German consumers, accustomed to energy security and stable prices, was profound. Wholesale prices rose higher than €300 a megawatt hour in summer 2022, from a pre-war price of around €20, hitting households and industries hard. The government declared that renewable energy would be given priority over concerns such as wildlife protection until greenhouse gas neutrality was reached, and set about lifting the financial burden of volatile prices. Among three big packages passed in a year was a limit on gas and electricity prices for companies and private consumers, in place until 2025. It “helped in the short term,” says May, of the German Energy Agency. “There were some industry closures, but fewer than was feared.”

The government also moved to cut demand by mandating a maximum temperature of 19°C in public buildings; suspending minimum heating regulations in private flats; banning the use of gas to heat swimming pools; eliminating the lighting of buildings or monuments and restricting illuminated advertising. In summer 2022, to discourage driving, it offered a €9 monthly train ticket—travellers could go any distance on any regional train in the country for a fraction of the typical cost. It was a huge success, with 52m tickets sold, and has been followed with a €49 ticket from May this year.

Those who had argued that Germany could do without Russian gas turned out to be right

But one fear remained: that the gas would suddenly stop. Just 11 weeks after the invasion, the German government claimed to have reduced its reliance on Russian coal, oil and gas to 8 per cent, 12 per cent and 35 per cent respectively. It hoped to replace Russian gas entirely by the following year, but it was not yet free.

In June 2022, in perhaps his most contentious move, Scholz announced that Germany would pass emergency legislation to reopen 27 coal- and oil-burning power plants, speeding the transition from Nord Stream 1. Although the chancellor later described the measure as “temporary”, it triggered domestic protests and international concern that Germany’s climate ambitions were slackening. Both Die Linke, a former East German socialist party, and the pro-Russian far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) tried to mobilise against the government, with little effect.

In the event, climate analysts agree that the impact on emissions was marginal. The law also brought coal back as a reserve in case of a gas supply crisis, and grid operators stress-tested the country’s three remaining nuclear plants, which provided 6 per cent of its power, to determine whether their useful life could be extended. They closed, just four months behind schedule, in April 2023.

In September, Germany’s oil and gas regulator took control of Rosneft’s shares in its three German oil refineries: Schwedt, near Berlin, Miro, near Heidelberg, and Bayernoil in Bavaria.

That same month Habeck could tell journalists in Berlin: “Gas deliveries from Russia no longer play a role in my security considerations.” Supplies had been unreliable for months: in March, Russia had closed the Yamal pipeline—which delivered 33bn cubic metres of gas a year across Belarus and Poland to Germany—after Warsaw refused to pay in roubles. Then, on 15th June, Gazprom claimed maintenance problems and cut the flow through Nord Stream 1 by 60 per cent, before closing it down completely in July. It re-opened a few days later, at 40 per cent capacity, before Gazprom shut off supplies again on 31st August, blaming a gas leak. On 5th September, even that pretence was dropped. A spokesperson for the Russian government announced there would be no gas unless “the collective west” lifted its sanctions on Russia. The final straw came on 26th September 2022, when several underwater explosions blew holes in both pipelines. In the weeks that followed, the governments of Sweden and Denmark confirmed that it was sabotage. Speculation continues over who was responsible. “The only thing that is reliable from Russia is the lie,” Habeck remarked.

However, after months of work with other suppliers in Europe to build, borrow and adapt infrastructure to import LNG and accelerate the shift to renewables, Habeck’s work had paid off. On 17th December, Scholz triumphantly declared Germany’s first LNG import terminal in Wilhelmshaven open for business. It had been built in record time.

Together with three further ports—one at Lubmin on the Baltic and two at Brunsbüttel and Stade on the Elbe, near Hamburg—Germany’s LNG storage capacity had gone from zero to 12.5bn cubic metres a year. Habeck nevertheless warned that accelerating the drive for renewables was still the priority.

Industries that had resisted change managed to cut their gas demand substantially through technical innovation, switching to different fuels and making adjustments to their output. Companies like BASF, for example, found that higher energy costs made producing some low-value products unprofitable.

Public opinion had adapted too, with a boom in demand for heat pumps ahead of a ban on new gas or oil heating installation from 2024. The target now is to install 500,000 heat pumps annually. “People who didn’t care about climate suddenly cared about their electricity bills and being warm in winter, and at football matches people who used to brag about their SUVs were talking about solar panels and heat pumps,” recalls Kreutzfeldt. “Electric car sales also went up,” he adds—some 833,500 new electric cars were registered in 2022 and the number of public charging points grew 35 per cent across the country, to more than 80,500. “It really changed something in the general public.”

Gerhard Schröder remains, for many, the villain of Germany’s long drama, but a move to expel him from the SPD failed. He did, finally, step down from the board of Rosneft and declined an offer to join the board at Gazprom, but his reputation was not enhanced when, in March 2022, his wife posted a picture of herself outside the Kremlin in an attitude of prayer. “It was completely misjudged,” says May. “This is a war, not an Instagram story.”

Schröder did lose one German privilege: last year the budget committee of the Bundestag withdrew the government-funded office customarily given to former chancellors for life. The four civil servants paid for by the taxpayer had already resigned. Schröder contested the decision in court. On 4th May 2023, the court rejected his case.

Schröder’s era had passed. The winter was kind and Germany emerged from the crisis with a renewed commitment to the energy transition. Saving energy for the planet was a cause that had previously moved a minority, but gained broad appeal when combined with the incentive of resisting Putin’s aggression. “In the end, it took less than a year,” says Kreutzfeldt. “After September 2022 there was no more Russian gas in Germany. It might even have been done faster, given that our neighbours had LNG terminals that were only at 50 per cent capacity. It turned out that our worries had been based on wrong assumptions.”

Habeck had managed to pass an astonishing 28 laws in nine months, the time it had taken his predecessor to get all his staff in place. Officials in his economic and climate ministry had worked 16 hours a day, seven days a week: they had found enough gas, persuaded people to save energy and accelerated the deployment of wind and solar.

One decision that remained controversial in Germany was the plan to build 50bn cubic metres of LNG terminal capacity when experts argued that 15bn would suffice. Some analysts think that Europe needs no more than three terminals, and by May 2023 Germany had already halved its initial plan to build 8 just for itself, correcting an expensive overreaction to a crisis that even the government’s critics agree it had handled well.

Looking back on 2022, Habeck and his officials would be justified in a sense of achievement. Heat pump installations rose 25 per cent and might have gone further with more skilled workers to install them. Dutch, French and Belgian LNG workers had doubled the flow of gas from their countries into Germany. The government had not lost support, while gains many feared the AfD would make did not materialise. The country entered the winter with a record 64 per cent of its gas storage capacity full. Those who had argued that Germany could do without Russian gas turned out to be right.

Still ahead is the challenge of raising the share of Germany’s energy that is renewable from 47 to 80 per cent by 2030. The government believes this can be covered by an additional 57 gigawatts of onshore wind turbines, 22 gigawatts of offshore turbines and 150 gigawatts of photovoltaic capacity. To get there, Germany needs to quadruple its annual construction rate, according to Habeck, commissioning an average of five new turbines a day. Onshore wind expansion, once bogged down in the cumbersome bureaucracy of permitting that routinely took years to clear, has been freed by a series of legal reforms to speed up planning, licensing and buildout. Habeck has challenged state governments and industry representatives to give the construction of some nine gigawatts of backlogged turbines the green light.

Germany has finally come through the energy crisis; its stalled response to the climate crisis is now gathering speed.