Two weeks after Alaa Sadeq Faraj disappeared in 2007, another man answered his mobile phone. “It was an Iraqi man. He didn’t tell us that they had killed him. He just said, ‘Go to the morgue’,” recounts Alaa’s brother, 51-year-old Mohammed Sadeq Faraj. “We went to the morgue to check, and we didn’t find his body.”

Alaa was 34 years old on 15th September 2007, the day he went missing while on shift as a government security guard north of Baghdad. His family believe that he was killed by members of a Shia Islamist militia that, like many other armed factions at the time, was conducting kidnappings across central and southern Iraq.

Mohammed believes that it was Alaa’s kidnappers who used his phone, and that his body was never taken to a morgue but dumped in nearby farmland, never to be seen again. “For one or two years, we kept looking for him. We tried everything. We asked everyone we knew, but nothing turned up,” Mohammed says during an interview at the Baghdad home where he raised Alaa’s three children as his own.

Six years after Alaa disappeared, with no proof of life available, the family confirmed his death in the Iraqi courts. They showed me the paperwork that enabled his widow and children to each receive a monthly stipend of around $160 from Iraq’s “Martyrs’ Foundation”, a state-run body that supports relatives of those killed, wounded and missing after decades of conflict.

The Faraj family’s story is harrowingly typical of the trauma that still lives in millions of Iraqi homes. Kidnappings and killings were rife during the sectarian conflict that gripped Iraq after the 2003 US-led invasion to topple former dictator Saddam Hussein. It is normal for multiple family members to be dead or missing. It is normal for Iraqi millennials to recount childhood memories of corpse-strewn streets, of moving out of their homes because al-Qaeda showed up, of narrowly avoiding explosions.

Following the invasion, millions of Iraqis fled the country. More than 185,000 civilians died from violence between 2003 and February 2017, according to the NGO Iraq Body Count. There are no concrete figures on the missing, but the International Commission on Missing Persons says that up to a million people have disappeared over decades of violence both before and after 2003.

Twenty years after Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath party fell, Iraq operates—on paper—as a federal democratic republic with an autonomous Kurdish-majority region in the north.

Car bombs no longer rip through the streets of the capital on a daily basis. Snipers do not crouch atop buildings. Many fewer people are killed or kidnapped because of their sectarian or ethnic identity. US troops no longer oversee an ugly network of concrete checkpoints that once dismembered urban spaces. Islamic State, which swept through Iraq and Syria in 2014, no longer controls swathes of territory. There are moments of joy: the southern city of Basra recently hosted the Arabian Gulf football tournament—and the Iraqi team won.

But Iraq operates at a fraction of its potential. It still carries the burden of multiple traumas—including disappearances like Alaa’s—amid ongoing cycles of violence and impoverishment. Incompetence, corruption and dysfunction also mean that successive Iraqi governments have failed to build trustworthy institutions, according to former ministers and officials themselves, as well as analysts and political activists.

“Unfortunately, the strategic political mindset in Iraq has not reached the stage needed to build a state,” said Jawad al-Bolani, who served as Iraq’s interior minister between 2006 and 2010 and is now an MP. “Each state institution—the ministries and agencies—has problems as big as Iraq’s overall.”

The state simultaneously provides everything and nothing. Every year it puts thousands of people on the public payroll in unproductive jobs-for-life and spends billions of dollars subsidising fuel, the electricity network and basic foodstuffs. It provides benefit payments to victims of violence stretching back to the 1980s war with Iran.

Monthly spending on civil servants’ salaries, pensions and social welfare is roughly 7.3 trillion dinars (around $5bn), according to Mudher Saleh, an economic adviser to the Iraqi prime minister. That eats up at least half of what Iraq makes every month in crude oil sales, the state’s only substantive form of income, leaving little for service upgrades.

As a result, infrastructure is crumbling. The subsidised electricity network is so decrepit that in many places it only provides 12 hours of power a day. Homeowners and businesses resort to generators to make up the shortfall, their diesel fumes smudging skylines countrywide.

In the Opec group of oil-producing nations, Iraq is the second largest producer after Saudi Arabia, but much of the subsidised fuel is imported because authorities have not built enough refineries to process domestic crude.

Iraq’s leaders have not made the process of recovering from years of conflict any easier

While 4.5m people are employed in the public sector—and another 2.5m are on the retirement payroll—youth unemployment is high, at 35 per cent, according to the International Labour Organisation. The private sector is almost non-existent, thanks to a complicated set of vested interests and weak legislation. The number of government jobs acts more like a “warranty institution” or a “life insurance company” than actual social security legislation does, says Saleh.

With the state having dominated so many aspects of people’s lives for decades, there is an aversion to and even suspicion of private sector jobs, which come with fewer guarantees and longer hours than government work. “It’s like, you sit behind a desk, and the bigger the desk, the more important you are,” says Musab Alkateeb, who has led various private western firms’ Iraqi operations. People view private sector work as “demeaning” or equate it with “debauchery of some kind”, he adds.

Iraq’s leaders have not made the process of recovering from years of conflict or building a stronger private sector any easier. In vast government institutions, hierarchical management and corrupt practices reign. Employees and private sector workers who enter this maze describe frequent disputes between government departments that slow down decision-making and officials who prefer to work in silos.

“The vast majority of senior officials use their positions in their institutions to enrich themselves, their families and grow their patronage networks,” says a former Iraqi government official, on condition of anonymity. “Iraq is not led by its best and brightest or even cleanest. It is governed by the mediocre and greedy.”

Iraq comes 157th out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s latest corruption index, and reports of officials of all ranks taking kickbacks on government contracts are common. Last year, authorities acknowledged that high-level bureaucrats had stolen $2.5bn from state-owned banks. The money has not yet been fully recovered.

There is little incentive for most officials to modernise or give up corrupt practices—even when those practices stop Iraq working in ways that might help ordinary people live better lives. “Public sector officials are well paid and have jobs for life, so their motivation is to maintain the status quo and avoid reforms,” says Sajad Jiyad, a Baghdad-based political analyst.

A major feature of the Iraqi state in 2023 is a lack of digitisation. In labyrinthine ministry buildings, stacks of papers presented to ministers for signing in gold files symbolise public sector inertia. This breeds opportunities for corruption, as the paper-based systems make it easier to hide illicit payments. Again, there is no incentive to reform because many officials fear relinquishing power.

Old-fashioned systems also make it hard for Iraqi officials to communicate with foreign firms looking to invest in the country, handicapping efforts to bring in the sort of jobs and wealth that would reduce public sector bloat. “Very few people there [in the ministry] have emails—the communication is just paper -based,” says Hassan al-Janabi, a former minister of water resources. “I think I was the first minister who brought in PowerPoint for my senior managers, and they were struggling. They didn’t know how to use it.”

There is also an atmosphere of paranoia and habit of top-down governance, which both stem from Iraq’s history of Ottoman and British occupation, Saddam’s dictatorship and the power-grabs that followed his removal. “The government’s reflexes after 2003 are very much based on an autocratic system whereby it’s, ‘We are in charge, you don’t get to tell us what to do—we tell you what to do.’ There’s no exchange,” says Alkateeb.

“Under Saddam and post-2003, [even] water issues have been considered as a state secret, up to this very moment,” says al-Janabi, who describes Iraq as “al-dawla al-aqima”—the sterile state—because of its dysfunction and unproductiveness.

Iraq today is a very young country: around 40 per cent of its 42.2m people are under 15 years of age, according to the Planning Ministry. Its population is growing fast, too, by 2.5 per cent a year, akin to many sub-Saharan African countries and far above the World Bank’s 1.3 per cent average for the Middle East and north Africa.

The youth bulge means that many Iraqis have no direct knowledge of what it was like to live under Saddam Hussein. They hear of his brutality from older family and friends, but they are not satisfied with their current leaders, either.

While elections take place and anyone can set up a civil society group or political party, many Iraqis feel that the power-sharing system at the core of the country’s politics hinders rather than helps them. The arrangement is broadly known as al-muhasasa—a quota system, in which politicians divvy up positions within the state among themselves, strengthening their patronage networks and enabling graft in the form of kickbacks and bribes.

“Altogether, and particularly in comparison to the Middle East, I think Iraq still has democratic institutions that can be either further developed—or they can fall apart,” says Marsin Alshamary, a research fellow with the Harvard Kennedy School.

Other characteristics of democracy are constantly threatened, too. Across the country, journalists and activists who criticise powerful political players often go missing, or are detained or killed.

Things are particularly brutal for Iraq’s women. So-called “honour” killings take place frequently. In some areas, women are visibly absent from public places. Girls are often not allowed out by their parents, while female labour force participation is just 11 per cent.

“As women, the biggest danger we face is that we don’t have the right to even demand our personal rights—to choose what we learn or study, or to travel,” says Maryam Samir Ali, a journalist and women’s rights activist. “It’s my right to choose my husband, the right person, whom I want to share my life with; it’s my right to live somewhere I like, in safety. But, honestly, we are deprived of all these things.”

While freedom is fragile, some basic indicators of quality of life have improved. The number of children dying under the age of five has nearly halved, from 45 in 1,000 live births in 2000 to 25 in 2020. Sanctions on Saddam’s regime long isolated Iraq from the world, and their removal enabled access to travel, foreign goods and the internet. But that’s little comfort to the millions of Iraqis who live on a pittance and cannot afford those things now anyway.

The country’s poorest province is Muthanna, a four-hour drive south of Baghdad. Most areas here have poverty rates of over 40 per cent, where poverty is defined as having to live on less than 105,000 dinars (around $70) a month, according to a World Bank study.

Al Hilal is one of Muthanna’s poorest areas—nearly three-quarters of its population lives in poverty. When I visit, Enhaira Raheyef Shannan points to the cracks in the ceiling of the shack where she lives. She is tiny inside the folds of her black abaya, her rasping cough a painful interruption to every sentence.

There is no air conditioning to ease the 50°C heat of an Iraqi summer, and no escape from the damp of winter rain. “When it rains, I feel like a duck,” she exclaims, with the sort of resigned humour so common among Iraqis. “I stand outside in the rain because I’m scared of the roof falling in on me.”

Her son, Saad Aouni Abed, lives next door in a similar breeze-block hut with his daughter and wife. Their home has a dirt floor and bits of plastic covering the bare windows. Saad brings in around 100,000 dinars a month from casual labour jobs on nearby farms—not enough to support his family. Enhaira clutches a wizened handful of foraged leaves covered in soil—it will make for a free meal. “Security is better these days, but in terms of cost of living, it’s really hard,” says Saad. “I borrow money to pay for food.”

Girls are often not allowed out by their parents, while just 11 per cent of women are employed

In northern Iraq’s Kurdistan region, whose autonomy was recognised in the 2005 constitution, instability and unemployment are driving people to leave. The town of Qaladze sits among gracious mountains, but hope is seldom found here. It was razed by Saddam Hussein— the wider area was one of the first to rebel against him, in a 1991 uprising—and while the town was rebuilt, today people cannot find jobs. They feel let down by their current leaders.

Many say that the two political families that dominate the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), the Barzanis and the Talabanis, have enriched their coteries at the expense of the man on the street. “We revolted against Saddam because we wished for a prosperous, democratic and civilised Kurdistan, but it didn’t turn out like that,” says Abu Bakr Bayez, Qaladze’s mayor. “Why do you think people are leaving? They wouldn’t unless they felt they had to.”

In the past two years, 7,000 young people emigrated from the Qaladze area alone, Bayez says. Many take dangerous smugglers’ routes to Europe. Some go missing on the way, adding to the thousands of Iraqi souls already lost to war.

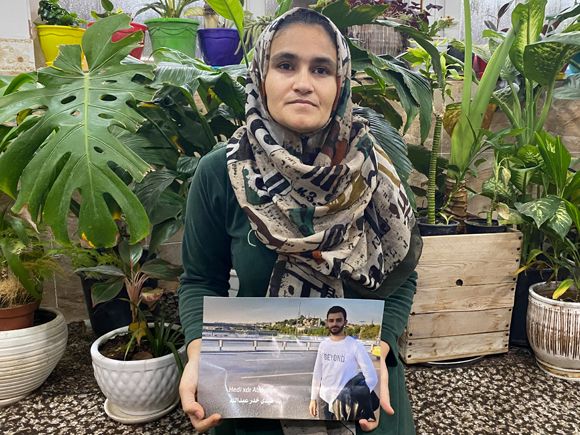

One of them was Hedi Khdir Abdalla, 22, who vanished after the boat he was travelling in sank off Crete in July 2021. He had been aiming to get to the UK, where friends had promised they would work together in a barber’s salon. “He left because he didn’t have work here: our parents are sick, and he was trying to get a job to help them,” says Hedi’s sister, 32-year-old Saresh Khdir. The only reminders the family has of Hedi are photos and a peace lily that he potted before he left—one of many joyful plants in a home filled with sorrow.

What can the world learn from Iraq and the failures of the US-led invasion? Perhaps that there are limits to superpowers’ abilities to nation-build. “Personally, that’s my first and foremost lesson—this question of, just what is the ability of an outside power to impose a new regime on a country like Iraq?” says Douglas Lute, who was George Bush’s deputy national security adviser on Iraq and Afghanistan. “I think the Iraq experience should give us pause—or better, perhaps, humility—in our ability to impose an answer from the outside.”

In 2023, many Iraqis’ lives are characterised by what is missing: the loved ones they have lost, like Alaa and Hedi; the lack of opportunity offered them by a dysfunctional government; the money wasted on kickbacks; and the hours of productivity lost to power cuts. The country’s young population still has so many reasons to want to live fuller lives.

“They want to feel that they are human beings,” says Maryam, the women’s rights activist. “They don’t want to feel like they are constantly a slave to things—a slave to their bosses, to their families, to their surroundings, society, and its traditions and norms. It’s our most basic right and we feel as though we cannot breathe.”

Additional reporting: Stella Martany in Qaladze and Ahmed al-Haddad in Baghdad