I left to escape a crumbling American dream, but then found it hard to join the European one. Photo Prospect composite

As a young American living in Berlin, planning for the future is an exercise in optimism. My first visa was rejected three weeks after my 20th birthday; years later, valid visa in tow, I was rejected a second time while applying to renew it. It was fine, I assured myself as I left my appointment with a temporary permit, which at least granted me an extension of my stay and the opportunity to appeal the decision. With an American passport, my right to remain in Berlin had always felt like a privilege, not a guarantee. It wasn’t much of a surprise either, as Germany’s borders became have become a cross-party political battleground.

When I submitted my appeal in early 2015, Michael Fuchs of the Christian Democrats suggested elbowing Greece out of the EU; a few months later, Merkel announced that Germany would welcome one million refugees. Meanwhile, far-right party Alternative für Deutschland were planning their eventual ascent into the Bundestag in the 2017 federal elections. They volleyed about frail metaphors of colonisation: Europe is by, for, and with those whose names and blood reflected the land’s histories—those Roger Scruton called “indigenous Europeans.” The rest were invaders, pillaging Europe’s fertile soil. It’s a call to arms, often quite literally: in 2016, Franke Petry, the AfD leader at the time, told the Mannheim Morgen that German border security “must prevent illegal border crossings and even use firearms if necessary.”

The former empires that once ransacked nations around the globe now face a threat of colonialism in their homelands, they claimed. In a country with an ultra-nationalist party growing louder, even I, an American citizen who is very visibly not white, began to wonder: was I part of the so-called “invasion”?

The European dream

We move for many reasons. My parents moved to the States to chase the American dream; I moved, in turn, from Seattle to Berlin upon realising staying in America would leave me chasing a white whale destroyed by crumbling political stability and the shrapnel of late-capitalism. I wasn’t alone. Estimates suggest that there are around 16,000 American citizens scattered across Berlin, where we’re often folded into the same multikulti cache as visiting students and entrepreneurs, the pan-European twenty-somethings, and–of course–the Brits abroad.Around 18,000 British citizens have resettled in the German capital. There are many reasons why they move, and Britain’s crumbling politics has offered many more: the declining pound sterling, parliamentary musical chairs, and sinking coastlines, to name a few. And that’s not to mention the very real shortages in the daily trimmings, from toilet paper to fresh produce, that are feared should a no-deal Brexit take effect. Their lives are a testament to the EU’s belief in the freedom of movement across its borders. They can use local health care systems and public assistance; take jobs of their liking; leave their work without leaving their new homeland.

At first, there was land, then there were nations and borders, and now there is Europe, to which British citizens may soon be denied a right many assumed would be lifelong. In Berlin, however, the indivisible pan-European spirit lives on. In January, the local government invited British citizens to register for pre-emptive appointments to discuss their future in Germany should a no-deal Brexit take effect. Slowly but surely, my British friends and colleagues are being called to the Ausländerbehörde, known as the “foreigners’ registration office,” the bureaucratic hellhole where appointments are often booked out three months in advance. It is where I’d both been denied my visa and won my appeals.

Reports suggest that the British diaspora is being approved en masse: last month The Local found that of the 2,343 interviews with British citizens conducted thus far, 2,144 resulted in permanent residency permits. A bill submitted to the Bundestag last week proposed holding off the usual stringent visa requirements for British citizens hoping to stay in Germany. A yoga therapist noted that her interview at the Ausländebehörde was almost entirely in English, and described it the experience as one of “personal empowerment”; a freelancer described his meeting as “painless,” but frustrating: “It makes me angry because I don’t know anyone else who’s lost their citizenship before.”

Who belongs?

Hearing that the process is polished and refined for British citizens is a cause for celebration: Germany is known for its tedious bureaucratic pedantry, and the Ausländerbehörde is the worst of the worst. It’s a relief to know that my friends have not had to stand outside its gates in the snow at five in the morning waiting to book an appointment, as I did in 2017.But while I waited in the cold back then, I knew further down the road was a row of white tents where others were lining up. These were the tents for refugees from nations stuck in a legal purgatory who experience serious limitations on their ability to work, travel, and begin their new lives. They come from countries marked by political turmoil and the lasting effects of European colonialism and foreign military intervention.

As immigrants and expats, we’re often reminded that we can leave our new countries if we don’t like the local customs, and encouraged to do so when we can’t, don’t or won’t integrate. It is a point reiterated ad infinitum by locals when I’ve brought up the tolerance for casual racism common in Germany. At the same time, I wonder what it must be like for those who are still left out from the discussion entirely. I think of the descendants of Turkish Gästarbeiters (“guest workers”) who were brought over to help redevelop the economy in post-war west Germany. They were only expected to stay in the country temporarily and were treated as such. I wonder about people of Namibian descent in Germany, where streets are still named after the German colonisers who operated concentration camps in southwestern Africa; I wonder when they’ll have a seat at the table too.

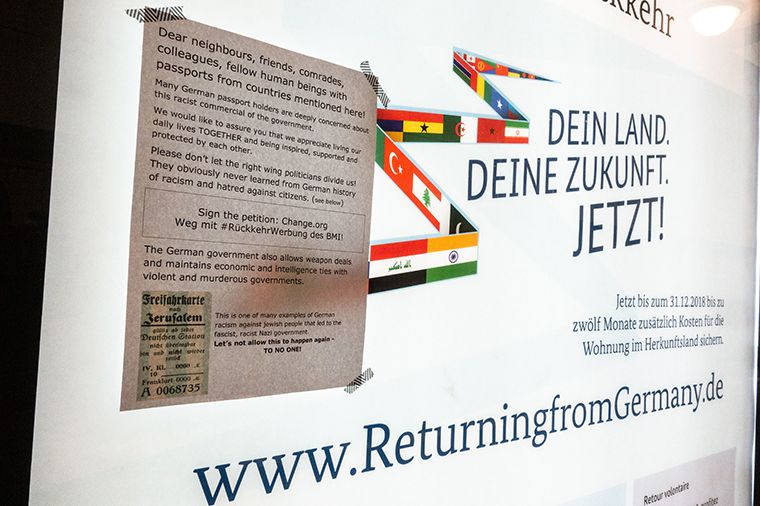

When we’re told to go home, it’s not just by our neighbours, colleagues or strangers in the street. Last Autumn, the Federal Ministry of Interior, Building and Community pushed an ad campaign in the predominantly Arab and Turkish corner of Berlin where I live. The campaign offered cash incentives for those who were willing to leave the country voluntarily: “Your country. Your future. Now!” the billboards read in German, with additional instructions in Arabic telling the reader to log onto a website called "ReturningfromGermany.de" for more information.

The unsubtle prejudices that mark our immigration systems aren’t just confined to Germany. It’s the same ideology behind Theresa May’s “Go Home!” vans, which rolled through postcodes with a higher concentration of ethnic minorities in 2013. In the UK, tabloids have spent the last two years fretting over the EU citizens who may have to return to the country of their passport when Brexit takes effect, but perhaps Berlin’s proactive measures towards Brits abroad will be met with a returned favour. Yet for the millions of us in the EU who were never sold the pan-European promise, it’s clear where we can and cannot call home.