In June, as Black Lives Matter protests were breaking out across America in response to the murder of George Floyd, the Pentagon agreed for the first time to consider renaming 10 military forts named in honour of Confederate generals. Donald Trump—New Yorker though he may be—greeted the news with outrage, declaring his absolute determination that these government buildings should continue to be named after generals who had led a war against that government, and fought to keep black Americans enslaved.

Most of these forts were first established as training camps during the First World War, under the administration of Woodrow Wilson, the first Southern president to take office since the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. In the decades following the conflict, America had to find a way to reunify after the bitterness of the fighting—and one of the things most white Americans at the time could agree on was white supremacism.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, nearly 500 monuments to Confederate white supremacy were erected across the country—many in the North—between 1885 and 1915. Over half of these were built in just seven years, between 1905 and 1912. This was the period during which Confederate mythologies of the Lost Cause of the noble Southern states and leaders gained purchase not just below the Mason-Dixon line, but across the United States.

Fort Gordon in Georgia, for example, was named for General John Brown Gordon, one of Robert E Lee’s most trusted generals. Gordon, who had a statue erected in his honour in the grounds of Georgia’s state capitol in 1907, was according to his biographer a “Grand Dragon” of the original Ku Klux Klan. Until his death in 1904, Gordon adamantly defended plantation slavery as “morally, socially, and politically right,” as did most of the white population in the former Confederate states. During “Redemption,” the period that followed the abandonment of the radical 12-year experiment known as Reconstruction, the South was “redeemed” from the project of interracial government and put back into the sole control of white Protestant men. The federal government soon honoured those who had sought to destroy it with civic landmarks across the country. The installation of the monuments reminded African Americans that their rights meant less to the nation’s leaders than did the dead white supremacists who lost a treasonous war to keep them in bondage.

The Floyd killing soon also sparked protests against racial injustice in the UK. One of these protests, in Bristol, brought down a statue of the British slave-trader Edward Colston (1636-1721), who had donated some of the profits from his lucrative dealing to civic philanthropy in London and Bristol. Colston was an official of the Royal African Company, reputed to have sold as many as 100,000 west Africans into slavery in the West Indies and the Americas.

It was almost 200 years later, in 1895, when Britons were first seeing their claims to imperial dominance challenged, and labour unrest was building at home, that Bristol business leaders decided to raise a statue to the “wise and virtuous” Colston. In the US, the analogous efforts at shoring up existing power structures led to the establishment of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1894, followed in 1896 by the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Both groups worked tirelessly to raise monuments to white supremacists, Klansmen, and slaveholders all over the American South.

The two projects’ simultaneity on opposite sides of the Atlantic was not a coincidence. They reflected an affiliated endeavour to promote ostensibly “Anglo-Saxon” values and leadership, one of remarkable longevity. One of the memorials that protestors have sought to remove this year is the bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest, a slave-trader, Confederate general and first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, which sits in the Tennessee State Capitol. (Initially blocked by legislators in June, it is subject to further wrangling.) It was completed as late as 1978. These monuments do not symbolise “national” history or heritage: they symbolise the structures of white governance and power derived from the transatlantic slave trade.

Over the course of three centuries, more than 12.5m Africans were forcibly displaced across the Atlantic, as humans were exchanged for goods—textiles, tobacco, alcohol and guns—and then sold on as enslaved labour to produce more of the raw materials for trade, especially the sugar cane of the West Indies, and the cotton and tobacco of the American South. Although some argue that Britain led the way in “abolishing slavery,” history is never that simple. Many 19th-century British leaders resisted abolition, and long after Britain had outlawed the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, it persisted in other British-held territories until 1833. Even after that, Britain continued to profit in a host of ways from the practice.

“Whether it is Trump tweeting about forts he’d never heard of or Johnson warning against the removal of statues, they are confusing history with mythology”

Take the textile industry, which accounted for the livelihoods of almost 20 per cent of Britain’s population and for 40 per cent of its exports in the early decades of the 19th century. Seventy-five per cent of its raw cotton was grown in the American South and harvested by slaves, keeping costs down. That’s before discussing the conspicuous role of sugar cane in the 19th-century British economy. It was also out of the profits created by the slave trade that other—enduring—transatlantic industries grew, including transportation (shipping and railroads), as well as insurers, brokers and financiers who profited as middlemen.

Around this trade system, there also circulated shared ideologies and stories that developed to make sense of, and justify, the imperial race-based marketplace. The two nations’ political cultures had distinct identities, of course, and sharply differentiated histories, but they were divergent branches of some deeply shared roots. Sometimes the alliances were conscious and deliberate, as when Cecil Rhodes created his scholarships to undo what he saw as the pernicious effects of American independence, in an effort to reunite “Anglo-Saxons” in shared white supremacism. Others were much less so, as when British audiences gathered to watch The Black and White Minstrel Show from 1958 to 1978. It’s impossible to know how many involved in producing or consuming the programme understood the work they were doing in furthering its fundamental message—that black people are sub-human figures of ridicule—or strengthening its transatlantic purchase. But that didn’t stop this message from being absorbed.

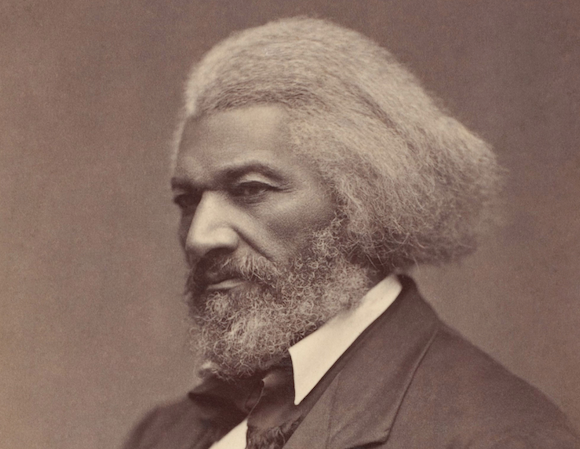

There are important stories to be told, involving more complex transatlantic exchanges than the crude swapping of stories to reinforce white supremacism. Take the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who travelled throughout the US and Britain in the 19th century arguing against the pernicious effects of slavery and white supremacism. He began life in bondage in Baltimore under the name Frederick Bailey, before escaping to New York and deciding, like many former slaves, to rename himself to claim a free identity. A friend suggested he take the hero’s name—Douglas—from an immensely popular 1810 poem, The Lady of the Lake by Sir Walter Scott. He liked the sound of “the Black Douglass,” he later said, for its associations with “the free hills of old Scotland,” which had seen many a “fierce and bloody conflict between liberty and slavery.” And so Frederick Douglass stepped into history.

It is telling that Douglass had not even read Walter Scott before being shaped by his work. Scott’s influence was so pervasive in 19th-century Britain and America as to have become ambient, part of a cultural atmosphere that Anglo-America still breathes to this day. The Lady of the Lake, a tale of Scottish clan leaders struggling for power against King James V, instantly inspired a London play of the same name, which transferred swiftly to America; by 1815 it had been performed in Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Baltimore and Washington DC. When Scottish folk hero Rhoderick Dhu appears, his clan sings a -martial anthem, “Hail to the Chief who in triumph advances!” and the song travelled around the country. At an 1815 celebration of the Peace of Ghent, ending the Anglo-American War of 1812 (a shared culture did not guarantee a smooth path from colonialism to independence), “Hail to the Chief” was played for the first time in honour of the American president. A tradition was born.

As well as inspiring a cult of the Highland clan, in poems like Sir Tristrem in 1804, Marmion in 1808, and The Bridal of Triermain in 1813, Scott also prompted an Arthurian revival. Three years later, Malory’s Morte d’Arthur was published for the first time since 1634; Tennyson would soon follow with “The Lady of Shalott,” his own Morte d’Arthur, and the Idylls of the King, and the Pre-Raphaelites would start painting, reinforcing the Arthurian craze.

Then there was Ivanhoe. Set in 12th-century England, Ivanhoe is a historical romance about a Saxon knight whose personal loyalty to the Norman King Richard the Lionheart proves a catalyst for conflict. Scott explained that his novel was inspired by “the existence of two races in the same country,” by which he meant the “vanquished” Saxons (marked by “the free spirit infused by their ancient institutions and laws”) and the victorious Normans (“the flower of chivalry”). The book’s 1819 publication, complete with obligatory allusions to King Arthur and the Round Table, was part of a wider medievalist revival that began with the vogue for Gothic, and soon led to a historically incoherent mélange of British archaisms, with chivalric knights, ladies fair, jousts, wizards, Saxons, Normans, squires, friars, cavaliers, troubadours, King Arthur, Highlanders, and the occasional Don Quixote all jostling in the cultural imagination. Out of the same impulse came the reimagining of the obscure fourth-century Greek Christian martyr St George, who was already England’s patron saint, as a medieval knight and a national ideal of masculinity.

We can see medievalism’s effect in the US in the appropriation of the word “minstrel” to describe itinerant white American performers in blackface. But even as these entertainers in the American South were singing about “Jim Crow,” a minstrel character who would eventually bestow his name upon segregationist laws, minstrelsy was travelling back to British music halls, where it lost most of its American baggage but retained the racism, becoming a popular fixture. The minstrel figure, like statues of white slavers, worked in the UK as a defence mechanism—bolstering a sense of white nationalism through the long decades when Britain’s imperial hegemony was first newly rivalled, and then began to decline.

Scott’s stories of different “races” jostling within one nation also supported the emerging theories of biological racial difference. Scott himself was not writing in defence of white supremacism per se, but rather drawing on archaic mythologies to navigate conflicting ideas about national identity. His popularity stemmed from his stories’ ambivalent balance between nostalgia for heroic traditions and faith in progress, mapped onto tales of sectarian conflict. Ivanhoe, for example, was inspired by English historian Sharon Turner’s popular History of the Anglo-Saxons, published between 1799 and 1805, which depicted the English as direct descendants of medieval Saxons.

“When British audiences gathered to watch The Black and White Minstrel Show, how many understood they were furthering its message—that black people are sub-human figures of ridicule?”

That interest in the Saxons itself can be traced further back to the ideological debates in the 17th and 18th centuries over constitutional monarchism, which claimed from the distant past of Saxon England an “ancient constitution” of heritable liberty that was crushed in 1066 by the conquering “Norman yoke.” These legends travelled to the Americas with English colonists in the 17th century, and when the time for America’s own insurrection came, the myth of Saxon liberty offered a ready justification. The revolutionary generation in America saw themselves as legitimate heirs to the political traditions of free-born Saxons.

Thomas Jefferson was one of America’s foremost Saxonists. Although he stopped halfway through Ivanhoe (“the dullest and dryest reading” he had ever experienced), he traced the right of independence back to “our Saxon ancestors,” proposing that Hengist and Horsa, the mythical founders of Saxon England, “from whom we claim the honor of being descended,” should be engrained on the Great Seal of the United States. Jefferson fetishised the Anglo-Saxon language, saying it was “of peculiar value” to study as Americans would “imbibe” with it “their free principles of government.” In other words, Americans’ legal right to reject the authority of King George turned on their supposedly Saxon heritage. They tended not to dwell too much on the fact that the king was also, quite literally, “the Elector of Saxony”—this kind of mystic nationalism always liberates itself from the tyranny of facts.

These assertions of natural, heritable rights soon mutated into assertions of natural, heritable superiority. Those benefiting from those burgeoning modern forms of slavery, colonialism and imperialism felt increasingly impelled to justify their dominance. Over the course of the 19th century, scientific, historical, political and religious arguments were produced to explain the “natural” supremacy of Anglo-Saxons, laying the foundations for British imperialism, as well as American exceptionalism including in its expansionist form of manifest destiny. The argument began to mutate, no longer claiming rights on the basis of a shared tradition, but rather on tribal bloodlines. Thus in 1836 a Vermont newspaper told its readers: “To our precious Saxon blood, we are indebted, it seems, for our laws, our liberty, our intelligence and our civilization: not to the ‘wisdom of our ancestors,’... [but] to our blood; that is to our family descent.” The argument flatly repudiates that rights are derived from political tradition, claiming instead, quite explicitly, that they are a matter of biological entitlement.

The “natural” freedom of Anglo-Saxons in the American North also defended, quite easily, chattel slavery in the American South. A Virginia newspaper argued in the same year: “It is peculiar to the character of this Anglo-Saxon race of men to which we belong, that it has never been contented to live in the same country with any other distinct race, upon terms of equality; it has, invariably, when placed in that situation, proceeded to exterminate or enslave the other race in some form or other, or, failing in that, to abandon the country.” In other words, don’t blame us for slavery and genocide, we’re just Anglo-Saxon.

What first the historical and then the biological theories did was to invent the category of the “modern Anglo-Saxon.” White Americans did not, initially, identify themselves as Anglo-Saxons at all; the idea of the “White Anglo-Saxon Protestant” or WASP had no purchase. Of course “white Protestants” were everywhere—and always in charge—but the idea that Anglo-Saxonism, as a racial identity, had anything to do with it had to first emerge and then evolve to justify the existing realities of power.

White supremacy was always the implicit premise of Anglo-Saxonism, and the tide of history soon allowed its advocates to make this increasingly explicit. Britons like Thomas Carlyle and then Francis Galton and Cecil Rhodes argued that the success of Anglo-Saxon imperialism proved their inherent superiority and rights to empire; white Americans looked at enslaved or subjugated black people or decimated native tribes and concluded they deserved their devastation.

The power of these ideas extended beyond the “colour line.” They began to gain purchase just as large waves of new immigrants from western Europe arrived in the US in the mid-19th century, giving rise to a new movement called “nativism,” which argued that the bloodlines of this new immigrant stock, including the Irish and (notwithstanding the geography of Saxony) the Germans, were inferior to the glorious Anglo-Saxon heritage of the “native” English settlers. There was also racial violence against Mexicans: from the mid-19th century on, nearly 600 of them died at the hands of American lynch mobs. (Trump has this summer spun out imaginary scenarios in which “a very tough hombre is breaking into the window of a young woman whose husband is away”; a “tough hombre” is none-too-subtle code for a Mexican.) These immigrants, too, would deserve what happened to them.

Sir Walter Scott’s romances fell into the fertile soil of this broad set of ideas about tribal identity. Again and again, Scott returns to the theme of divided loyalties: his heroes have to navigate the equally valid claims of competing factions, while being buffeted by large historical events, and—somehow—not just survive, but emerge with a viable sense of identity. His writings became a national mania in a United States still trying to decide who it was and find a usable past. American towns changed their names to Ivanhoe and Waverley, while a vogue for jousting tournaments, which had started on English aristocratic estates, took America by storm—with knights-errant, gentle ladies and wandering troubadours. As late as 1870, Brooklyn’s Prospect Park hosted a “Grand Tournament” of “doughty Knights.”

But it was the antebellum South that was most captivated by Scott’s mythologies: gentlemen mounted on armoured horses to tilt, joust and show off their fake heraldry. There were fashions for velvet tunics, ornate caps, and affected titles such as the “Knight of the Golden Lance,” while the fetishisation of aristocratic notions of “gentility” took hold. In 1854, a newspaper in Richmond, Virginia praised a tournament of “jousting in honor of their ladies and performing many a deed of derring-do” for bringing “civilised, refined and chivalrous” ideals to the “barbarous regions of West Virginia.”

This was something more than playacting, however. These tropes became an active part of how the Confederate South defined itself against the North: the inherent violence of its system was romanticised into a noble chivalric way of life. Ivanhoe’s “two races,” coexisting in an uneasy truce, chimed with Americans who felt that the divide between North and South was growing unbridgeable. In absorbing Scott and other medievalist mythologies, Americans began to trace an Anglo-Saxon history back through the English Civil War, so that New England settlers in the North became Puritan-Saxons and Southerners became Cavalier-Normans. Indeed, white Southerners before the Civil War described themselves as Anglo-Norman more often than as Anglo-Saxon.

The South’s pastoral nostalgia was set in conscious opposition to the industrialised modernity of the North. And the aggressive feudalism of the pageants recast black slaves as loyal serfs, bound by devotion to the land and the family they served. At the same time, it reinforced the cult of Southern white womanhood, their purity defended by gallant plantation aristocrats. An ascendant Southern nationalism absorbed this self-serving mythical genealogy and defended race-based slavery as a venerable tradition, with the plantation as merely its latest incarnation.

The cult of medievalism also locked the South into a defiant backwardness. Scott was so central to its identity that Mark Twain, who grew up in the slave state of Missouri during the 1840s, later railed against what he called “the Sir Walter disease.” The author had, Twain insisted, done “more real and lasting harm, perhaps, than any other individual that ever wrote.” In fact, “Sir Walter had so large a hand in making Southern character, as it existed before the war, that he is in great measure responsible for the war.”

Scott’s stories were equally responsible for shaping the region’s bitter response to defeat. In The Lady of the Lake Rhoderick Dhu lights a cross to signal an uprising against the king, as Scott invokes an ancient Scottish custom for gathering the clans, known as the Crean Tarigh, or Fiery Cross. The image of a clansman burning a fiery cross as a call to arms against a tyrannical sovereign authority was revived in 1866, just after the Civil War ended, by a ragtag white supremacist group in Tennessee.

“The simultaneity on opposite sides of the Atlantic was not a coincidence but an affiliated endeavour to promote ‘Anglo-Saxon’ values”

As the Confederate South continued to seethe against the “War of Northern Aggression,” and the (de jure, if not always de facto) emancipation of the slaves, the old romantic idea of a local “white knight” defending the Southern way of life, and especially white Southern womanhood, took a vicious turn as paramilitary groups with quasi-medieval names like the Knights of the White Camellia sprang up. The Ku Klux Klan—“an institution of chivalry,” its founders declared—derived its name from the Greek for circle (kuklos) and Sir Walter Scott’s clans. The “clan” was formed of “knights” and “wizards” rather than the more obvious chieftains or warriors, and burned fiery crosses in acts of vigilante violence it preferred to regard as rebellion against a tyrannical federal government. Its occultism was partly an intimidation tactic; the first Klan also designated various members “Ghouls,” “Hydras,” “Cyclops” and so on. But the “Knights of the Ku Klux Klan” were also an outgrowth from decades of the Sir Walter Disease. Beyond the imagery, Scott endowed the postbellum South with its animating myth of the Lost Cause, and the nobility of remaining loyal to a defeated ideal, and Ivanhoe became its code. (In To Kill a Mockingbird, set in Alabama during the 1930s, Jem Finch destroys the flowers of racist old Mrs Dubose and his punishment is to have to read Ivanhoe aloud to her.)

The first Klan was only a scattering of murderous groups that lasted about five years, and was seen off by federal forces in the early 1870s. But its mythology endured. In 1905, Thomas Dixon, Jr published The Clansman, a wildly popular genesis myth for the first Klan that draws on Scott: his Southerners have the “blood of Scottish kings” flowing through their veins, and invoke “the old Scottish rite of the Fiery Cross” to “send a thrill of inspiration to every clansman in the hills.” In reality, the only thing medieval about the historical Klan was its brutal violence, but Dixon’s novels were hugely successful in reinforcing the white South’s fantasies of nobility—and in so doing helped spread an idealised version of white masculinity across America.

The Clansman, in turn, inspired The Birth of a Nation, DW Griffith’s hugely successful cinematic paean to the Lost Cause in 1915. (Griffith was the son of a Confederate colonel.) Griffith said he hoped the film would “create a feeling of abhorrence in white people, especially white women, against colored men.” That it did. Six months after its release, a young Jewish man named Leo Frank, who had been convicted, probably wrongfully, of murdering 13-year-old Mary Phagan, was taken from an Atlanta jail and lynched. That Thanksgiving, 16 men gathered on the summit of nearby Stone Mountain, lit a fiery cross, and declared the Klan reborn.

The second Klan started small, but intense national media coverage gave this fringe band of vigilantes publicity they could never have afforded. Klan membership skyrocketed, as did discussion around the “white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant” identity it purported to defend. Soon the Klan achieved its greatest influence—not in the old South, but in the nativist heartland of the Midwest, where Anglo-Saxonism also exerted a tremendous pull. In 1923 an Indiana newspaper argued in highly typical terms that Klansmen were “not going to stand by and see the country overrun by a set of people from foreign countries,” or to have “their children inter-marry with those of other races than the Anglo-Saxon race, which has gone down in history as the most progressive and the most civilised of all races.” The Klan, the article added, would ensure “that soon a flag would float from every school-house and a Bible would be on every school desk,” because the Klan, he said, stood for “America first”—the very slogan that, in the 21st century, Trump would make his own. A mythical identity had willed itself into existence, one that continues to shape American—and world—history to this day.

The nostalgic feudalism of Lost Cause mythologies permeates the 1939 film Gone with the Wind. The film—based on Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel, which was itself partly inspired by her love of the writings of Thomas Dixon, Jr—opens with a paean to a “land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South. Here in this pretty world, Gallantry took its last bow. Here was the last ever to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and of Slave.” This spring, HBO temporarily removed the film from its catalogue, intending to return it once it had been framed with historical context. A tiresomely predictable outcry against censorship followed.

All of these mythologies, whether they produced a minstrel show, a statue, or murderous groups like the Ku Klux Klan, were productions of nostalgia, not history. Nostalgia is driven not by knowledge of the past, but by desires in the present, and therefore is always anachronistic, an act of cultural projection.

Today, as people around the world insist that we look afresh at our tangled histories, a handful of white male leaders respond by doubling down on the old stories. But whether it is Trump tweeting about forts he’d never heard of until they were about to be renamed or Boris Johnson warning that the removal of statues of white supremacists would be telling a “lie about our history,” they are confusing history with mythology.

The removal of these statues is an attempt to advance closer to the truth, in part by moving beyond monolithic symbols that choose glorification over the difficult work of history. If communicating our history were really the motive of those who raised statues, they wouldn’t have chosen such an uncommunicative form of ancestor worship. One might even call it primitive.