In the Czech Republic they are known as “Stones of the Disappeared” (Kameny zmizelých). When my mother Hedy died in Finchley in 2018, I wanted to connect her back to her Czech origins. She was born in Brno into a comfortable middle-class life. Her father Albert and grandfather Jakob were dentists. In the Spring of 1942, along with most of her family she was forcibly transported to the Terezin ghetto. Three years later when the ghetto was liberated by the Russians on 8th May (VE day), out of the wider family who had been deported, most had been killed. From the individual transport to the ghetto, 56 of the 1,001 deportees survived to witness the liberation. The remaining 945 were murdered, together with over 77,000 Czech Jews who did not survive the Holocaust.

Brno was known as the “Manchester of the Czech Republic” with its thriving textile industry. The capital of Moravia, it was a prosperous industrial town and until 1939 home to a substantial Jewish community. Today about 300 Jews remain and the legacy of the former Jewish life is hard to uncover. The city itself, like much of Czechoslovakia, survived the war virtually intact, as there was minimal fighting and little bombing. There are still the typical central European gabled houses, wide cobbled boulevards, charming squares and Baroque facades from past centuries.

On a hillside overlooking Brno sits the Villa Tugendhat—an outstanding example of modernist design created by Mies van der Rohe and commissioned by a well-heeled Jewish family in the 1920s, for their newly-married daughter Greta, wife of Fritz Tugendhat. Today, after much post-Communist renovation, the house is a widely-visited world heritage site. Simon Mawer made the villa the protagonist of his award-winning novel The Glass Room. Many, but not all, of the Tugendhats fled from Brno before the war. Their descendants became prominent names in British politics and law.

The Jewish origins of Villa Tugendhat are almost invisible in the publicity material. And similarly the fate of Brno’s Jews. The only city memorial to them lies in a shabby park, away from the centre. It features a large black slab with water running down into a surrounding small pool. There are no signs or markings on the slab. The only clue is faded Hebrew lettering, disfigured by algae, under the water at the base of the block. Apparently the proportions of the block are Pi—3.14—to indicate the infinite misery endured by the Jews in that time—pretty obscure for anyone seeking to find out about this lost community.

My mother grew up in a large apartment on the first floor of a mansion block—spacious enough for live-in help. The building still stands today on Jostova, one of the central cobbled streets running through the city. Wooden trams sweep past in the middle of the wide boulevard. Her father’s dental surgery was on the ground floor, today replaced by offices. Close inspection of the stonework reveals where the surgery’s plaque was hung—the colour is faded and there are four small holes in the wall from the fixings. That was the only reminder that the family had been there. Albert and before that his father Jakob who had worked here had both died in the camps with no graves or memorials.

I had seen the small brass stolpersteine (stumbling stones) commemorating former Jewish residents in the pavements of Berlin and other European cities. They had intrigued me and once I delivered a JDov (Jewish TED) talk at King’s Place in London on their significance. After some false starts, I tracked down a local contact. Boris Selinger, a Brno resident with Jewish origins, was instrumental in organising the stones—choosing the inscriptions, confirming the locations and obtaining city council permissions.

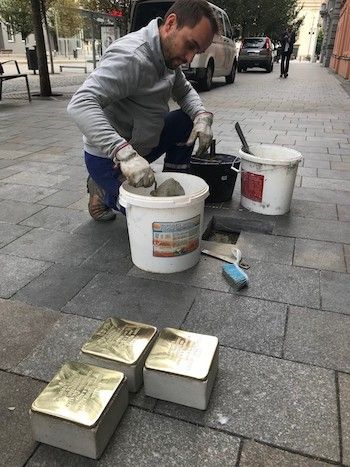

Early on a Sunday morning in September 2018, we rendezvoused in the Jostova boulevard with Boris and a local stone mason who had fashioned the three small plaques. He drilled holes into the pavement and then inserted the memorial stones into the ground for my mother and her parents; fixing them with cement, wiping away the residue and polishing the brass surface. We then said Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead. Boris and the mason left to install more stones—this time coincidentally for relatives of Fritz Tugendhat (his aunt and cousin) who were also deported to Terezin and later murdered in Majdanek.

The whole experience was slightly surreal, arriving on a Ryanair flight and feeling suddenly a weight of memory and sadness. Here on this elegant boulevard the German troops had marched in March 1939 when they invaded Bohemia and Moravia, and I imagined the family watching from the windows as the trap closed in on them.

In the desperate days before and after they had tried multiple ways of escaping. During the 1938 Sudeten crisis they went to stay with relatives in Bulgaria—Albert’s sister Marianne had moved her family there from Brno. Albert himself, veteran of the 1914 war (a cadet in the Austro-Hungarian forces), was called up to the reserves in response to the Nazi threat, but Hedy with her mother went to stay in Sofia and she attended a local Czech school. Assured by Neville Chamberlin’s promise of “Peace in Our Time” they returned to Brno after the Munich deal was signed.

In 1939 my mother had a place on one of Nicholas Winton’s Prague Kindertransports to the UK, but in the end as an over-protected 10-year-old only child, her parents could not face letting her go into the unknown. Later there was a prospect of going to Palestine, again through Albert’s enterprising sister Marianne, who had secured permits from Bulgaria and taken her own children on the Orient Express via Istanbul and Damascus south to the new promised land. But these permits were costly and whilst most of Albert’s funds were invested in the dental practice, it needed his father Jakob’s agreement to release sufficient money. Jakob thought Palestine was a ridiculous idea and pronounced that there was no need to run away as he had no personal quarrel with Hitler. Hedy’s mother Emmy used her considerable charm to plead with him to provide the funds, but to no avail. The family had other connections in the UK, and when the invasion was imminent in March 1939 they had already sent a consignment of luggage and household goods to London. They bought tickets and went to Prague intending to board a flight, but the airfields were already closed. They returned to Brno as the rumour was that empty properties would be immediately requisitioned by the invading forces.

To begin with, not that much changed and Albert was probably secretly relieved to have abandoned the escape plan. He was a poor linguist and knew that life as a foreign refugee would be a struggle. But in due course they were made to wear the yellow star. Hedy had to leave her state school for a Jewish school and slowly the exclusion from mainstream society began—no longer able to ice skate, visit the cinema, ride a bike, sit on certain park benches or visit shops outside specified times for Jews. And then the order came to shut down the Jewish school. Eventually they were thrown out of their flat and forced to occupy one room within a shabby communal house shared with other families. From there the deportations began as friends and family disappeared week by week. Life in Terezin and beyond has been documented elsewhere and my mother rarely mentioned it, although she did record an interview with Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation.

In the months after our trip to Brno, when I was grieving for my mother’s recent death, I felt comforted to know that she and her parents’ names were being seen by the hundreds of pedestrians wandering along Jostova boulevard. Walking the streets of the city I had felt a real sense of place. It was easy to imagine the life of the Jewish bourgeoisie in the early 20th century—German speaking, a rich cultural environment, multiple communal organisations, philanthropic societies and activities. Under Kaiser Franz-Joseph this part of central Europe was one of the most enlightened and tolerant places towards Jews. I understood my forbears past experience as a genteel, comfortable existence within a family that felt well integrated with the surrounding community. Indeed so integrated that one of my mother’s uncles, also deported to Terezin and later murdered in Treblinka, was even called Adolf.

A year later I returned to Brno to attend, again with the help of Boris, another stone-laying ceremony. This time we were remembering three more of the disappeared; Jakob, my great-grandfather who as an elderly diabetic survived only a few weeks in Terezin. Helena, Albert’s younger sister, was 38 when she was killed—she had recently married Ernst Schallinger. Ernst had previous experience of incarceration. He enlisted with the imperial Austrian army in 1914 and was later taken prisoner of war by the Russians.

As the Nazi threat loomed, Helena and Ernst sought to escape to Palestine and had obtained the permits and sent luggage on ahead. But they were anxious about arriving in a strange country with no livelihood, so their project was to acquire a bread-making machine—which they had heard was a useful trade in Tel-Aviv. They were organising this purchase and delivery when the Germans invaded—suddenly it was impossible to leave. Helena and Ernst were transported to Terezin in early 1942. In June 1942 they were deported on again, to their death. Of the hundreds of onward transports listed to the death camps from Terezin, that particular one with 2,033 people (none of whom survived) appears as “destination unknown.” One archive indicated that it might have been destined for Sobibor but this remains unclear. The luggage they had sent to Palestine sat unopened for years—in the hope that they might one day reappear to claim it.

We had few pictures of or details about Helena and Ernst—just the memories from her sister Marianne who had died in Tel-Aviv in the 1980s. There was no one left to remember them so my Israeli cousin and I tracked down Jakob’s address—around the corner from the Jostova boulevard on the aptly-named Jakobsplatz. It was a gabled three-story property, opposite the onion-domed church of St Jakob, now occupied by smart offices and flats. Once again on a quiet Sunday morning we watched as the mason chiselled into the pavement and then carefully laid three stones commemorating Jakob, Helena and Ernst. As he finished polishing the brass, the bells of St Jakob rang out. Again we said Kaddish and wondered what the employees working there would think, when they arrived on Monday morning and traversed the shiny stones telling this sad story of disappeared neighbours.