The last week of May 2020—one of the most horrific in American history—may also be remembered as the week in which the election of 2020 was decided.

It started calmly enough. On Monday 25th May, Memorial Day, the presumptive Democratic nominee for president Joseph Biden appeared at a veterans’ war memorial near his home in Delaware. Biden was with his wife Jill, and was carrying a wreath. Like millions of other Americans, he has been following “stay at home” orders and it was the first time he had been glimpsed in the flesh outside his immediate neighbourhood, where he walks and bikes, in more than two months.

And it was only a glimpse. The Bidens’ appearance was unannounced. Reporters immediately scrambled to the park, hoping for live interaction with a candidate who had mounted a remarkable comeback from seeming political death at the start of the year, with a sequence of primary victories in some 20 states in every region of the country: large states and small, on both coasts, in the north and south, and in the Midwestern heartland.

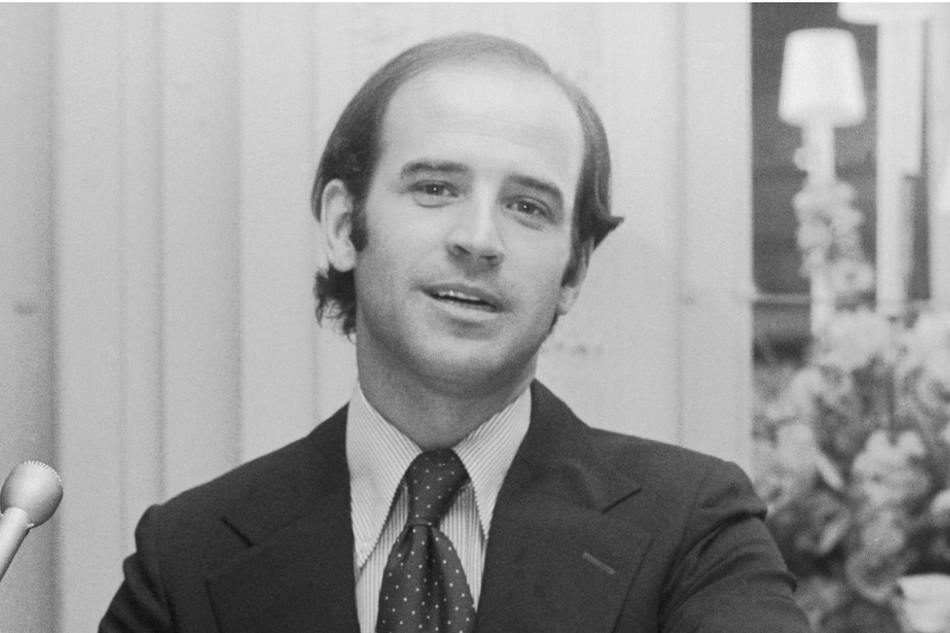

Throughout his long career—which stretches over 50 years, including two terms as Barack Obama’s vice-president, seven terms in the US Senate and two years as a county councilman before that—Biden has been famous, or rather notorious, for loose-lipped volubility. But not this time. After laying the wreath, he spoke only a few terse words. (“Never forget the sacrifices that these men and women made. Never, ever, forget.”) With his snowy-white hair, and dressed in a black suit with a black mask and black sunglasses, he looked like an aged hero in a Hollywood action film. Then he climbed back into his SUV and was driven home, there to resume the virtual campaign he has been waging via camera, screen and pre-recorded video.

[su_pullquote align="right"]“American exceptionalism, our supposed exemption from the furies of history, has ended with a vengeance”[/su_pullquote]

“Nearly every morning,” New York magazine reported in mid-May, “Biden spins through an early Peloton ride in the upstairs weight room, dresses (formally, no sweatpants), drinks his breakfast shake, and sits at the phone in his study awaiting the latest updates on the world’s misery.”This disciplined routine runs counter to Biden’s instincts and history. He is the most conventional of old-school American politicians—gabby, flesh-pressing—and the product of a distant time. Way back in 1972 in his first Senate campaign, energetic, cocksure and with a blinding smile, he challenged an established and much older Republican incumbent. The odds were steep but Biden never doubted he could do it, relying on his connection to voters. “He was sure he knew where the people stood,” Richard Ben Cramer wrote of the young Joe Biden in his classic study of the 1988 presidential campaign, What it Takes. “They were like him, he was like them… he’d be their voice… he’d stand up for them. Even if it meant picking a fight.”

Biden turned 30 after election day, barely making the constitution’s minimum age for the Senate. If he wins in November 2020 he will be the oldest man ever to be elected president and will take office at the age of 79, surpassing Trump, who turns 74 in July.

This battle of the geriatrics will unfold against entirely novel conditions as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, which—our dumb American luck—has come in an election year and upended everything.

For one thing, Biden’s sweep towards the nomination was interrupted mid-surge. He was trapped in the technical limbo of “presumptive” rather than confirmed nominee because the schedule of later primaries was suspended, including in the key states of California and New York (a judge has now ordered the latter to go forward). He was only able to clinch the delegate total he needed in early June when further primaries were held, with mail-in balloting. His party also had to postpone its national nominating convention from mid-July to mid-August—assuming it will be held at all. If it is, it will be nothing like the coronation of times past—nominee, running mate and party shown off to the nation —but in all probability will be spare, skeletal, perhaps cheerless, like the National Football League games we are told will be played in empty stadiums.

And after the nomination it could get even stranger—a “split-screen” campaign through the autumn, Biden and Trump debating in “feeds” from separate, secure locations. That’s assuming Trump doesn’t manage to avoid the debates somehow—he fears his challenger enough to have pressured the president of Ukraine to concoct an investigation of him, resulting in Trump’s own impeachment. Their vice-presidential candidates will also “meet” remotely, while surrogates rage at one another on Twitter and on rival cable TV networks.

Still worse is the growing sense that while the pandemic may be a meteor none could have foreseen, its arrival threw a searchlight on pathologies that have been festering beneath the surface for many years—gaping disparities in our healthcare system, inequalities in our social services, profound racial tensions and rotted fibres in our putatively strong economy.

Of course much of the globe is reeling from coronavirus, but the US has been hit far worse—far more infections and far more deaths—than any other country, any two other countries. With this comes the shocking feeling that “American exceptionalism,” our supposed exemption from the furies of history, has ended with a vengeance. God has stopped smiling on us.

Are there parallels? The jobless numbers of 40m in the space of 10 weeks—excluding uncounted workers in the gig economy—invite comparison with the Great Depression. The chair of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, has said unemployment could reach 25 per cent—Depression levels. And many of those jobs may not come back.

One difference is that this time, here as in other countries, the shutdown was induced by the government. Before then, the economy seemed strong; Trump was counting on it to get him a second term. But the US economy had also looked strong in the days leading up to the Depression. In fact, then as now, deep cracks were visible to those who troubled to look—unregulated stock trading, dangerously low farm prices, assembly-line manufacturing that produced more goods than the public could afford. So, too, the pre-pandemic 21st-century economy was structurally weak; built on arcane financial-sector transactions, inflated real estate, and the yawning chasm between the rich and the rest, atop a rickety foundation of deregulation, privatisation and the outsourcing of critical manufacturing and supplies.

All this has been brought home in the most palpable way. American hospitals have had to pay extortionate prices for ventilators; the paper masks most of us wear are imported from China. Giant deposits of wealth—for instance, exorbitant commercial real estate in cities like New York—could all but disappear in the next months and years as people “telework” or flee to the countryside. Industries once worth billions—professional sports, Hollywood films, research universities—are shuttered with no one able to say when they might re-open.

[su_pullquote align="right"]“Loyal Democrats hope that those voters whose voice Biden vowed to be in 1972 will somehow swing it in 2020”[/su_pullquote]

Meanwhile, the government’s response has been toxic denial. At the outset, Trump and his allies in the media depicted the virus as a hoax being spread by his detractors. This still sometimes seems to be the president’s view and much of his party’s as well, even as the death toll rises. State and municipal administrators (such as New York’s Democratic governor Andrew Cuomo) pleaded for assistance—money, equipment, respiratory masks—which Trump unaccountably refused to provide or to mobilise his government to manufacture. This truculence resulted in tens of thousands of deaths. Even after Trump’s much-delayed and grudging acknowledgment of the facts—which he still avoids mentioning in public—the administration and its allies in Congress failed to meet the most pressing challenges. We lag far behind other countries in testing, yet the states are being pressured to reopen beaches, barbershops—and massage parlours. And for all Trump’s vaunted promise to revive the stalled economy, he has taken only baby steps. While governments in Denmark, Germany, and the UK intervened to provide workers with a substantial portion of lost wages, a US administration beholden to the self-serving prejudices of wealthy campaign donors has made sure to enrich itself while letting the labour force struggle into destitution.A $2 trillion stimulus package was sold to the public as Trump’s 21st-century version of Roosevelt’s New Deal, but it actually replicates the blinkered and self-defeating business-first remedies of FDR’s hapless predecessor, Herbert Hoover. Beyond the tax cuts and rebate that dominated the arithmetic, it reeked of antique, poorhouse-era almsgiving. A transfusion of cash to “small businesses” dispensed through private banks has been worse, exactly the boondoggle for well-capitalised companies that Trump’s opponents warned about.

Hoover is remembered today as a cold-hearted incompetent. This is unfair. He was in reality a humane leader undone by his inflexible devotion to laissez-faire principles that history had discredited. Trump acknowledges no principle whatsoever, apart from the imperative—shared, it must be said, by his party and his perfervid base of supporters—of a second term.

This year’s Memorial Day ceremonies inevitably had the undertone of a newer message of mourning, not least because the holiday came just ahead of a second moment that Americans had been anticipating with trainwreck fascination. This was the announcement, on Wednesday 27th May, that the American death toll had reached 100,000 (the actual total is almost certainly much higher). This is more than the combined US deaths in every war since 1945—Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq; more deaths too, as Mehdi Hasan pointed out on The Intercept, than “ever died in a single year from HIV/Aids, drug overdoses, gun violence, or car crashes in the US… more than 33 times the number of people who died on 9/11.”

The pandemic toll has been especially high among the country’s minority populations, which include its 40m African Americans and 60m Latinos, who together make up almost a third of our population. These groups often work high-risk frontline healthcare jobs—as orderlies, nurses, emergency service workers—or in onsite workshops where infections spread most easily. They are disproportionately poor, and as such suffer the most from the porous medical safety net of a nation that declines to grant healthcare as a “right” and instead relies on pasted-together coverage linked to (now fast-vanishing) jobs. Many live and now die in solidly Republican “red” states—blacks in the Deep South, Latinos in Texas—which refuse to extend health coverage to the extent allowed for under Obamacare.

The stubborn race gap in American society leads naturally into the third, and perhaps the most crucial, event of the last week of May. On the night of Monday 25th, hours after Biden visited the veterans’ memorial, a white policeman in Minneapolis—one of the country’s prize cities—knelt on the neck of a handcuffed African-American, George Floyd, and would not let up, ignoring the man’s pleas (“I can’t breathe”) and those of onlookers. Instead the officer continued to press his knee against Floyd’s neck for almost nine full minutes and kept it there after he died. This killing was captured on video. The police officer, Derek Chauvin, and three others were fired. Chauvin was later arrested and charged with third-degree murder and manslaughter.

By then Minneapolis had erupted in riots—a police station was set ablaze—and sympathetic demonstrations by mostly young people broke out in cities across the country, more than a hundred in the space of a week. The protests became the first event to interrupt and displace the pandemic in the continuous TV and livestream news cycles that consume even more hours than usual now that so many Americans are in lockdown. The disturbances they watched—which included the live, on-air arrest of a CNN reporter who was covering the scenes—recalled for many the street battles that brought America to the brink of civil war in the late 1960s.

This is the dangerously divided America that Biden and the Democrats will inherit if they win in November—a victory that would, for it to be meaningful, have to come with a substantial, filibuster-proof majority in the Senate.

At this point there is no evidence this will happen. Polls point towards a fairly tight race between Biden and Trump. Some still give Trump the edge in important battleground states—the ones Obama won twice but Hillary Clinton failed to carry in 2016. But other analysis shows Biden doing better than the Democrats did last time with crucial demographic constituencies, in particular the burgeoning elderly vote. And Trump certainly scores poorly on handling the pandemic.

Yet for the time being it is Trump who still holds the advantage—not because he commands a majority. He never has and hasn’t needed to. Hillary Clinton got three million more votes in 2016, but he won anyway, thanks to the antique apportionment of the electoral college, designed in 1789—along with other measures overcounting voters in the slave-holding south—to ensure outsize influence for smaller, less-populated states.

Obama’s victory was seized on as evidence that the Democrats were riding a deep demographic tide, which could carry things their way for many cycles to come. But the opposite appears to be happening, because of how that changing population is distributed. The most diverse states are also the most populous; progressive voters may be increasingly more numerous, but are also crowded together with less of a say than over-represented, smaller, rural populations. California has 40m inhabitants and two senators. Wyoming has 550,000 people—and two senators. “By 2040, 70 per cent of Americans will live in 15 of our 50 states, and 50 per cent will live in just eight states,” writes Vox’s Ezra Klein in his well-argued new book, Why We’re Polarised.

That’s half the problem. The other half is so-called “affective polarisation,” the idea that tribal loyalty to one side or the other in our bitter and continual culture war saturates everything we feel and think. In such a climate wearing a face mask—or rather, not wearing one—constitutes a forceful political statement. The much-bruited “message” of the Memorial Day observances was that Joe and Jill Biden wore masks, while Donald and Melania Trump did not.

[su_pullquote align="right"]“The danger will come if the election follows a different path, whose trailblazer was Richard Nixon”[/su_pullquote]

Biden’s promise—the reason he won the nomination—is that he can heal this breach. The calculation, and the original premise of his candidacy, was a bit of retrospective calculation done by Hillary Clinton. She would be president today, she has written, “if just 40,000 people across Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania had changed their minds.” She meant the “white working-class” voters who supported Obama in 2008 and often again in 2012, but who switched over to Trump in 2016.This is the fateful strategy of refighting the last war, yet Democratic Party leaders—its elders and kingmakers, and mainstream journalists—firmly believe in it. Biden paid dearly for the perception, which he has done little to dispel, that he is out of touch with the new base of the Democratic Party—young, progressive, impassioned—and that he is rather the handpicked “electable” choice of its elites. And his weaknesses grew large, prohibitively so it seemed, when he was trounced by the genuinely radical promise of Bernie Sanders in early contests in Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada.

But then, the most dependable Democratic bloc, African-Americans, came through for Biden in South Carolina and set him on his path to victory. His nomination is owed to those voters. The mess and fury of Trump’s reign, plus nostalgia for the dignified Obama-Biden years, was a help. Black voters well remember Biden’s deference and loyalty to America’s first black president. They remember, too, the suffering in Biden’s life—the death of his first wife and their infant daughter in a car accident shortly after his victory in 1972; the loss of his son, Beau, to brain cancer in 2015. Biden’s story is one of overwhelming loss and nakedly-exposed grief. Important, too, has been his long political history as a working-class tribune. Loyal Democrats whose single overriding concern was taking the White House back from Trump concluded that he might be able to reach the parts of the country that Clinton couldn’t—and that those voters whose voice he was sure he could be in 1972 might swing it once again.

In that long-gone era it was a plausible argument. There were still many such Democrats, some of them Irish Catholics like Biden. As his website says, he was born in the “blue-collar city of Scranton in northeast Pennsylvania,” adding that Biden’s father “worked cleaning furnaces and as a used car salesman.” But among today’s ultra-diverse and often highly-educated Democratic activists, Biden is a rarity—to the right of the bulk of the metropolitan base. It didn’t help when Biden was snared in #MeToo assault allegations—albeit nothing like the allegations against Trump, and coming increasingly into question—but enough to sow doubt with younger voters. For such reasons, the strategist Stanley Greenberg, who helped devise Bill Clinton’s winning campaign in 1992, has urged Biden to make the progressive Elizabeth Warren his running mate. She is said to be high on his list of candidates, and has made it clear she wants the job. Biden has said his choice will be a woman in any case.

But such a bargain could hurt him with that magical 40,000, who voted for Trump last time and will now be suspicious of Biden’s courting of a Democratic left that disdains the very idea of Making America Great Again. And that suspicion could count for more than his talking like a blue-collar Democrat circa 1972, a vanished species, as Biden all too often seems to be. When he launched a campaign slogan of “No Malarkey” he was using an authentic word from his era. It just sounds false today when no one speaks that way or knows anyone else who does. Wavering working-class Trump voters will often be ageing, but not so aged as Biden himself. “Malarkey” will no more endear him to them than Hillary Clinton’s use of “okey dokey-artichokey” did.

In times of emergency, and this is one, American elections in the modern era have followed one of two paths. The route Biden has sensibly chosen is the one that works best for Democrats. It is modelled on the 1932 election, in which FDR blamed the Depression on Hoover and made it stick before he’d worked up a plan of his own beyond the ethos of “try something.” Such a campaign begins and ends with the economy. Biden is said to envision a vast post-pandemic economic programme “more ambitious than FDR’s.” Even before the crisis he had begun to adopt some of his party’s more progressive ideas—like Sanders’s “Medicare for All” and a higher minimum wage—and these seemed pitch-perfect when the pandemic came and exposed the vulnerability of the uninsured and showed how inadequate most people’s life’s savings are. This could be the opportunity for Biden to become once more the voice of “the people.”

The danger will come if the election follows the second path, whose trailblazer was Richard Nixon in 1968. In that assassination and riot-packed year, when radical young activists were also alienated by the Democratic party machine, Nixon honed a politics of polarisation, of racial discord and bitter cultural enmity. Trump did the same when he announced his candidacy in 2015 and—amid the new protests and uprisings—he appears to be doing so even more lewdly this time.

Nixon’s version was so successful that in his 1972 re-election, as Biden was elected as a Democratic Senator in Delaware, the Republican president carried the state with 60 per cent of the vote and won 48 others in one of the biggest landslides in history.

The week that began with Biden’s wreath laying, moved on to statistical confirmation of the grim exceptionalism of America’s coronavirus death toll, and ended with Trump being reprimanded by Twitter for inciting violence (the tweet read, “when the looting starts, the shooting starts)”—and then cowering in a bunker beneath the White House, while 45m Americans were under curfew. It is a week that moved the African-American political philosopher Cornel West to say to CNN that the nation was collectively “witnessing America as a failed social experiment.”

Within days, tear gas was used to clear a Washington DC crowd from a church near the White House so that the president could pose with a Bible, which as he held it for the cameras looked like a prop he’d been handed on the walk over. (“If he opened it instead of brandishing it, he could have learned something,” said Biden.) In a threatening conference call with governors and mayors, Trump told them if they did not “dominate” the streets with force, he would send in the US army—as Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy did some 60 years ago, only they did it to safeguard civil rights activists, not commit violence against them.

The question is who will pay for the failed experiment that West spoke about—Donald Trump, who was sworn into office promising an end to fictive “American carnage” and now presides over a real American mausoleum? Or Biden and the Democrats, who will likely be denounced by Trump’s campaign and its auxiliaries as sympathisers of the myriad “outlaws,” “criminals,” “Antifa terrorists” or, in a word more congenial to the president, “thugs”—no matter how many are citizens demonstrating peacefully to bring about changes in policing which a majority of the country agrees need to be made.

Trump has said before that he was looking to Nixon as his model. Nixon too talked about law and order, defended the police in their clashes with protestors and waged war on liberal elites, returning with hatred the contempt they showed towards him and his voters. And Nixon too faced impeachment proceedings.

Even before the new and raw racial conflagration on the streets, it was plain that the Covid-19 pandemic had changed American life by feasting on latent poisons that have erupted in the Trump years but were present long before. Trump himself is more symptom than cause. Do Joe Biden and the Democrats have “what it takes” to cleanse it? Does anyone in our post-pandemic age? The lessons of history are few, and they are not encouraging.