On the evening of 31st January 2020, thousands gathered in Parliament Square to noisily celebrate the moment when the UK finally—after almost three years—left the EU. Two days earlier, on the other side of the Channel, MEPs had gathered in the European Parliament chamber to bid farewell to the UK with a rendition of “Auld Lang Syne,” before pressing on with its usual legislative scrutiny the next day.

The nature of the UK’s relationship with the EU was always bizarre. On one side, a politicised and fraught debate. On the other, the mundane, institutional business of EU membership.

Over the last few years, the UK focus has been overwhelmingly on its own side. But it is, in fact, in Brussels where the first and most sweeping changes have come. Since 1st February, for the first time since the early 1970s, there has been no British government representation in the EU institutions.

The UK no longer has a commissioner. Its officials and ministers no longer attend working groups or meetings in the council. The UK no longer has judges on the European Court of Justice. And the UK’s MEPs have also upped sticks.

Yet there is still a sizeable British presence in Brussels (and elsewhere in the EU) that has hardly been discussed: the well over 1,000 Brits who still work as EU civil servants. The UK’s exit has had a more profound impact on them than perhaps anyone else.

I have spoken to a number in recent weeks—from the commission, parliament, External Action Service and other institutions and agencies—to get a sense of what life is like now the UK has left. While many are grateful to the EU institutions for allowing them, where they have, to stay on, there remains deep anxiety about the future, concerns over how their nationality will affect their career prospects and, in some cases, a gnawing sense of already becoming outsiders.

The EU employs around 60,000 staff in total, roughly equivalent to the UK Ministry of Defence. Around half of these are in the European Commission, which is slightly smaller than the UK Home Office.

According to the latest data, there are around 700 Brits working in the commission, some 240 in the parliament and 50 or so in the council. There are a further 150 in other institutions such as the European Court of Justice (56) and the External Action Service (40), among others. There are also Brits working in EU agencies, although up-to-date figures are not readily available.

In the commission, Britons continue to play a sizeable role in many departments. They represent more than 5 per cent of staff in the Internal Audit Service and the Directorate-General for Climate Action. They are also particularly important for the EU’s language services, making up over 4 per cent of staff in the translation and interpretation departments.

The EU civil service is a complicated business. The rules on employment are set out in the 200-page EU staff regulation text; there multiple, overlapping grades; and there are a range of contracts, each with different implications for British employees.

The basic problem for Britons is that officials can only be appointed in the EU if they are nationals of a member state. Where does that leave existing British staff?

By a strict reading of the rules, officials can be asked to resign if they lose their EU citizenship. However, the commission has been generous in saying that this provision will not be used with British officials, ie those permanently employed as members of the EU civil service, essentially securing their jobs. The other institutions have tended to follow the commission’s lead.

For British staff on fixed or temporary contracts, it is very different. The EU’s Conditions of Employment state that such contracts should be ended where employees lose their EU citizenship. Again, the commission has sought to be generous, requesting that institutions apply derogations to UK citizens. Nevertheless, the employee will usually have to have a specialist skill required by their institution and such decisions are made on a case-by-case basis.

The European External Action Service (EEAS), the EU’s diplomatic corps, for instance, has temporarily extended British contract staff until September 2020. What happens after then is unclear. British staff I spoke to in the parliament had been granted derogations and this appeared to be standard practice in that institution.

But they will find it more difficult to transfer between the institutions in future. Their derogations apply only to their current institution. And not only will their horizontal movement be limited, but their vertical movement up the institutional hierarchy may also be restricted. Posts arising may in theory be open to Britons, but justification will have to be made as to why they would be chosen over EU citizens.

One British staff member in the parliament told me that they had already been discouraged from seeking a promotion. Giving the job to a British citizen would be politically impossible. Especially for more senior roles, domestic political support is often crucial. Needless to say, that is now absent for British staff, although many say they received little support from the UK government even before Brexit. Regardless of what the formal written rules may be, many Britons may be stymied in advancing their careers for this reason.

In principle, nationality ought to be neither here nor there. The code of conduct in the commission says staff shall act in “the Community interest” and that they “shall never be guided by personal or national interest.” Plus, the EU staff regulation forbids any discrimination on this, or any other, basis. “You leave your flag at the door,” as one official in the EEAS told me.

In many cases, however, the reality is less idealistic. Nationality does, and will, have an impact, especially on British staff.

One answer has been to change nationality. In the EU institutions, British citizens’ lives are made infinitely easier and their livelihoods more secure with EU nationality. As one employee in the parliament said to me, “Pretty much every Brit I know has either changed their nationality or is considering it.” One official in the EEAS said that they had even considered changing their British surname to pre-empt any discrimination.

For dual nationality Britons, they can simply switch. The EU system records employees according to their “first” nationality, a subjective choice made by staff and which can be easily altered. It is therefore nigh on impossible to know how many originally British staff remain in the EU institutions, as a substantial number have simply disappeared into the system under other nationalities.

This has been complicated by the commission changing how Brits were counted. Those who switched nationality after the UK triggered Article 50 are still counted in the data as British, whereas we have no reliable way of knowing how many changed nationality prior to that.

There were good political reasons for this change. There are broad guidelines (so-called “guiding rates”) about what share of officials each member state should have in the commission. This is calculated largely on population size. Germany, for instance, has a guiding rate of 13.8 per cent of all staff while Malta has one of 0.6 per cent. The council uses similar guidelines, as do other institutions. The commission was concerned that some Brits would change nationality and take up other member states’ quotas.

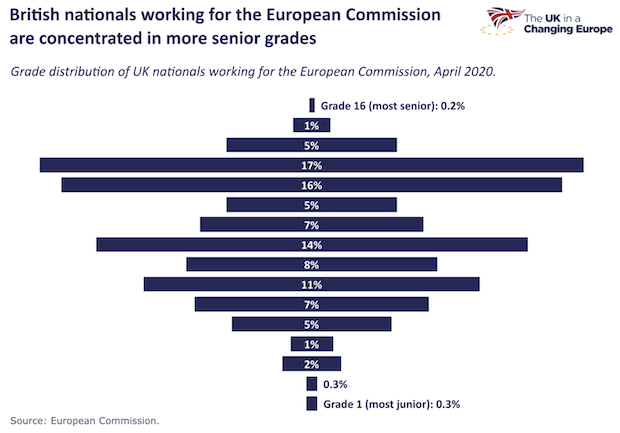

While not religiously applied, these guidelines are most strictly enforced in higher level, senior management positions, given these are the most influential roles. That becomes a problem if you have lots of Britons switching nationalities, as they are disproportionately concentrated at the top of the commission, as the chart below shows. This concentration also reflects a bottleneck in the system, with fewer roles at director and director-general level.

British citizens have also had a number of difficulties with national authorities since the Brexit vote. For instance, language certificates needed to gain citizenship in the Netherlands were not recognised, despite being awarded by the commission. There was also inconsistent application of citizenship requirements between different local authorities in Belgium, with a number of court cases taken against them by EU officials.

By virtue of having worked in Brussels for years, many Britons are eligible to apply for Belgian citizenship. When Britons moved to Brussels, they were issued with a “Special Identity Card,” giving them residence rights while working for the EU. However, this is issued by the Foreign Ministry, not local governments, and holders of these cards are told explicitly not to register with local authorities. Yet it is local authorities who make initial decisions as to whether the prerequisites have been met to apply for Belgian citizenship.

It is worth recalling that 12 EU countries do not allow dual nationality. For Brits whose only option to retain EU citizenship is via one of these countries, they face a stark choice: give up their British passport or, potentially, jeopardise their careers.

You might wonder what role, if any, the UK government plays in all this, given these after all are British citizens. A UK government spokesperson told me, “UK Government officials in Brussels are on offer to provide support to British citizens working for EU institutions, and engage the EU to ensure they are treated in line with their staffing regulations.”

But there is a notable contrast between the persistent and public reassurances sought by the EU regarding its citizens in the UK and the, to put it politely, more passive approach taken by the UK. Staff I spoke to had had very little engagement from the UK government. There is an impression that, perhaps for political reasons, the UK government is embarrassed by its citizens in the institutions, given most—though not all—supported remaining in the EU.

But the big questions are really for the EU itself. There are administrative and political restrictions that mean British citizens will from now on be at an undeniable disadvantage. You could say that flows automatically from the UK leaving, but the message from the institutions is that, especially for officials, little has changed. Yet, as an employee in the parliament put it, “You want to be considered equal and it’s really not the case. We are not equal.”