At the G7 summit in Biarritz in August 2019, the mood was distinctly one of a troubled family getting together to stage an intervention. Caught unawares on a video feed that was soon cut off, Angela Merkel sighed: “We can’t give the impression we are working against him.” An embarrassed Boris Johnson muttered agreement. “We will call him,” decided Emmanuel Macron.

One thousand days after taking power, this is how Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro is still regarded by the global community: another of the many threats they no longer believe they have a solution to. Even before he came to power, the deep chauvinist currents he stirred were a threat to minorities and the workings of democracy within his own country. But in power, borders cannot contain the chaos he has unleashed. He cheers ranchers’ attacks on the Amazon rainforest—the figurative lungs of the world—and endangers human lungs everywhere on the planet, through his wilful mismanagement of the border-sprawling coronavirus.

This puts Brazil, traditionally proud of being “everyone’s best friend” on the international stage, in a new and unfamiliar role. Now that Donald Trump, whom Bolsonaro devoted all his energy to courting, has left office, Brazil finds itself in the bad books of the entire world. The journalist Thomas Traumann, a former spokesman for the ousted ex-president Dilma Rousseff, has quipped that the last person to be so universally loathed by world leaders was Osama bin Laden.

But at home, Bolsonaro’s followers care no more for the opinions of statesmen or diplomats than they do for democracy or the rule of law. They take their cues from the president. Rallying the faithful on São Paulo’s Paulista Avenue, one of the busiest streets in the country, Bolsonaro told his enraptured audience that there were only three futures for him: “Being arrested, killed, or victory—and they won’t arrest me. Only God will remove me.”

Closer in tone to a Louis XIV or Charles I than Latin American authoritarians, this sort of parlance reflects a new desperation about the prospect of his prevailing under the rules. Ahead of the 2022 presidential elections, Bolsonaro’s approval ratings are shot. His main adversary is the former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who was convicted of money laundering and corruption in 2017. Lula was released early from his jail sentence of nine and a half years (by a judge, Sergio Moro, who would later become Bolsonaro’s minister of justice and public security) and has amassed such a commanding poll lead that he could win outright in the first round of voting: abject humiliation for a sitting president.

The possibility of defeat torments Bolsonaro, for whom macho pride and political success have always been inseparable. He would find it almost literally emasculating to lose, and—while plainly incapable of running the basics competently, or of managing Congress or the Senate, or turning the economy around—he can at least rail pre-emptively against democratic defeat at every opportunity. Bolsonaro and his country are now hostage and captor. This coming year will show—with memories of the last days of Trump in mind—where the resulting brinkmanship leads.

Born in 1955 in Glicério, São Paulo state, to a lower middle-class family of Italian and German immigrants, Jair Bolsonaro is almost a perfect product of Brazilian recent history. Bolsonaro’s character was formed by the military dictatorship that ruled between 1964 and 1984—and under which he grew up. Today, when he summons crowds to fill the boardwalks of Copacabana and Ipanema beach to beg for military intervention, he invokes the ghost of a demand made by a very similar demographic—upper-class, white-identifying and Christian—in 1964, when the military moved against the elected, reformist and left-leaning president João Goulart.

Sometimes it hardly seems to matter to Bolsonaro’s style of politics that he is, in fact, in power. Like a Hollywood reboot of a classic horror film, he draws inspiration from the original coup, and attracts fans by playing on the strength of nostalgia for the iconic original: slogans are repeated, symbols re-appropriated (everything from the shirt of the national football team to the “Love it or Leave it” anti-dissident slogans) and adapted to suit the modern audience’s expectations.

One specific moment in the dictatorship’s history formatively shaped the young Jair. In 1971, the deserter-turned-revolutionary Carlos Lamarca hid himself in the woods near the town of Eldorado, where the Bolsonaro family eventually settled. A few days later, the full force of the dictatorship descended on the otherwise unremarkable spot, with men searching every corner for evidence of Lamarca and willing to napalm the trees to smoke him out.

The adolescent Bolsonaro had none of the rebel sympathies that would be characteristic of most political comings of age. “I helped, discreetly as I was only 15, in the hunt for Lamarca in Eldorado,” he sometimes boasts. Historians are doubtful—the details don’t quite add up—but an invented origin story is, if anything, more telling.

Apocryphal or not, there is one deep truth in the president’s account of his part in the hunt for Lamarca: it is a story of personal revelation, a young man finding his vocation, namely a calling for the politics of brute force. This is a crucial point, because it is easy to misunderstand the aggression of his campaigning style, the vicious consequences of his attacks on the rights of indigenous populations in the Amazon, passion for looser gun regulations, and taste for violent police repression as incidental, the sort of tactics that cynical rulers around the world might resort to if it tightens their grip on power. The difference with Bolsonaro is that brutal force isn’t the means but the end: the violence is the point.

Lamarca escaped, only to later meet his death at the dictatorship’s hands. In a neat historical irony, young Jair would more or less follow in his footsteps, joining the Agulhas Negras military academy that Lamarca had graduated from. Though an unimpressive pupil, Bolsonaro thrived at sports, and found a comradeship among his fellow students. “There is,” he claimed in 1999 while he was—believe it or not—celebrating an election victory in Venezuela of a then-little-known colonel called Hugo Chavez, “actually nothing as close to communism as military life.”

From a man of the hard right that claim sounds surprising, but then Bolsonaro has never travelled with much ideological baggage, and has always had great feeling for the army. He was amply capable of solidarity with fellow officers, even though he never rose through the ranks. As an elected official he has been publicly dolorous about the end of Brazil’s dictatorship, but back then the young captain had pressing economic anxieties about the transition to life under civilian rule. He became known for causing a stir by complaining about wages in 1986 to Veja magazine, which then the following year got hold of the details of his plan to plant a bomb in the military base bathrooms as a protest. Bolsonaro was promptly discharged, which, whatever its disadvantages, made for an exit far more honourable than desertion.

His exploits won him a support base in the reactionary constituencies of Rio de Janeiro. Soon enough in 1988, in this newly created democracy, the former soldier was elected to Rio city council. The official story of the Bolsonaro firm (as told in an aggrandising biography by his son Flávio) does not present his discharge as idealism, but as the evasion of dark forces: supposedly, running for election “happened to be the only option he had at the moment to avoid persecution” by his military superiors. From there, it was a short step to being elected to Congress in the 1990 elections. A 27-year career there was sustained via a series of very small populist and conservative parties, which he approached as vehicles for advancement that could be boarded or disembarked from as convenient. (Even as he sits in power today, the president no longer has any party affiliation.)

But from the off he was a nationalist conservative by instinct: anti-gay, anti-abortion, anti-race equality laws and anti-environmental protections. His two divorces have never been a bar to his reactionary social policies: in power, he might not have felt able to go as far as the Taliban (who recently converted the Ministry of Women into a new Ministry of Vice and Virtue), but nods in the same patriarchal direction by renaming the Ministry of Human Rights the Ministry of Women, Family and Human Rights.

He has invariably displayed open contempt for Brazilian democracy—famously declaring that late-1990s president Fernando Henrique Cardoso ought to be shot—but has nonetheless quietly built a political dynasty. By 2018, three of his four sons had gone into politics and the family faced allegations (which have been denied) of connections to Rio death squads.

It was comedy that first introduced Bolsonaro to the mass of Brazilians. Topical satire show Custe o que custar (or Whatever it Takes, known in Brazil as CQC) could no more be expected to pass over Jair Bolsonaro than Have I Got News for You could have resisted booking Boris Johnson. From being just one of many curiosities in Congress, in the centre-left dominated Brazil of the 2000s, his standing as a fluent throwback to an earlier era steadily made him a household name. His statements reliably shocked and appalled—exactly as CQC intended. “My sons will never fall in love with a black woman or be homosexuals. They were well raised,” the congressman informed viewers.

Many a country has recently fallen for the charms of a noted TV performer. But Bolsonaro was not a wordsmith in the manner of Johnson, still less a dashing film star, nor even a captivating bogeyman enthusiastically firing people atop a golden tower. Instead, he was a curious relic: the symbol of a not-so-distant past, a regime that worshipped military power and chased dissenters into the woods with napalm.

Only in the mid-2010s did the joke prove to be grimly serious. “Bolsonaro was smarter than I was,” CQC’s presenter, Monica Iozzi, reflected mournfully in 2020. “Instead of denouncing such words, I was actually giving them room to grow.” The catalyst for the transformation of ear-catching loudmouth into potential leader was a national mood of deepening dissatisfaction with the ruling Workers’ Party. Though the party had improved the living conditions of many poor families, it had become engulfed in a cloud of corruption scandals, as well as a range of bitter (and sometimes internal) disputes which descended into a vortex of nastiness.

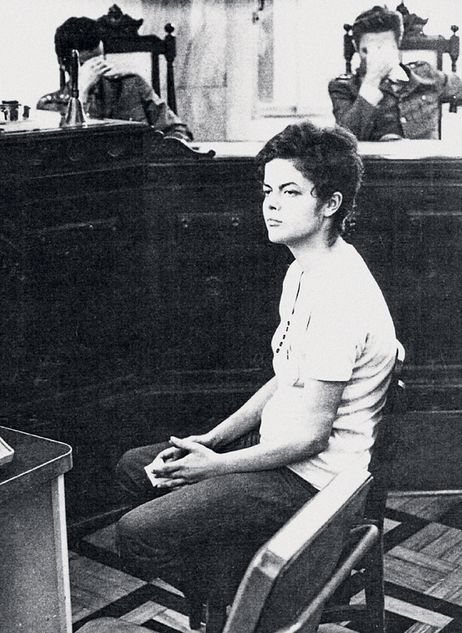

By the time president Dilma Rousseff had won her second mandate in 2014, the political world simmered under the heat emanating from the massive investigation known as Operation Car Wash (Operação Lava Jato). While all political sides were implicated in the endemic corruption revealed, it created an opening for an outsider who could at least claim to stand as a “drain the swamp” candidate. Moreover, the country was creaking under the strain of Rousseff’s surrender to austerity which had, after a lag for emergency stimulus, followed the financial crisis. The logic of retrenchment made all choices painful, and few leaders acquitted themselves well in its wake: suddenly Rousseff appeared hardened and clumsy where her mentor, Lula, had been flexible and sure-footed.

Rousseff, like the rebel Lamarca long before her, came to be an enemy against whom Bolsonaro would define himself not just politically, but personally. A former revolutionary who hated the dictatorship, a left-winger, and, most damning of all, a woman of unrelenting toughness, she might have been designed in a lab to represent everything Bolsonaro loathed and feared. In reality, she was cautious and moderate, but in the eyes of a resurgent far-right Rousseff was perverting the nation’s children against God, country and capitalism. Over the two years between Dilma’s downfall and Bolsonaro’s rise, Bolsonaro’s political guru (and a former astrologist) Olavo de Carvalho began to prophesy about the evils of her secret agenda: abortion would become the norm. Infants would be forcibly initiated into homosexuality. Religion would be banned.

Bolsonaro galvanised all these forces as only he could. In his speech voting for Rousseff’s impeachment, he praised Colonel Carlos Brilhante Ustra, the notorious head of the dictatorship’s torture unit which had brutalised Rousseff during her arrest as an anti-regime guerrilla in the 1970s: he showered praise on him as “the terror of Dilma Rousseff.” The invocation of Ustra electrified proceedings in a sinister manner, like the summoning of a demon in a black-and-white movie: watching it back, one almost expects screeching violins.

Referencing Ustra, rather than any of the generals who actually held the presidency during the dictatorship, could not have been more pointed. Brazilian presidents in those years liked to keep a high-minded distance from the murder and destruction that they regarded as a distasteful necessity: sometimes one orders the disappearance of young men and women because one must. Ustra, by contrast, was no pragmatist; like Bolsonaro, violence was his vocation.

“As with Boris Johnson on Have I Got News for You, TV satire made his name”

Despite the fame achieved through such cartoon villainy, when Bolsonaro announced his candidacy in 2018 the consensus was that he was doomed to be a first-round failure. As a candidate he was often unprepared to a degree that would have embarrassed a man of less unshakable force—he responded to every question about economics with “I’ll ask Paulo Guedes” (one of the neoliberal “Chicago Boys” who studied under Milton Friedman, who Bolsonaro made minister of finance). He talked passionately only about punishing criminals, arresting opponents, shutting down feminists, silencing queer activists and, in one way or another, reasserting dominance over traditionally oppressed peoples such as indigenous tribes and the Afro-Brazilian quilombolas (descendants of escaped slaves).

Like the supposed wise heads in the US who for so long insisted that an “establishment lane” Republican would see off Trump in 2016, Brazil’s pundits rolled their eyes and reassured everyone that the political machine “will start running and crush him.” But turning the old cogs didn’t work the same magic when so much of the campaign took place via WhatsApp groups, fake news websites and Twitter. The campaign was further energised by an attempt on Bolsonaro’s life made by a disgruntled and mentally unwell member of the public. The paranoid Bolsonarista slogan that those “behind it all” were desperate to stop their man gained new currency. And amid a tanking economy and rising violent crime, the broader mood of the country was anger: someone “had to pay” for what has been “done” to us.

In his hour of victory, he reheated a well-worn campaign slogan: “God above everything, Brazil above everyone.” But it was well understood—not least by him—that his elevation reflected the national desire for vengeance, and a promise that there would be blood.

In 2019, less than a year into Bolsonaro’s government, the bright skies of São Paulo were suddenly covered in a thick black smog, rolling in like an apocalyptic vision. The sky remained dark all day, and wildfires continued to rage out of control across the country.

The government had expressly allowed for this unprecedented environmental devastation. Bolsonaro was elected partly by a coalition of farmers and miners in the north of the country. He saw the Amazon as unfinished business, admiring the chaotic historic images of the vast and notorious Serra Pelada mine and the logging operations, legal or otherwise, that took place across Brazilian history but intensified during the dictatorship. In the mythos of the military government, the forest was a wild frontier: its people and their ways of life were outside of civilisation and opposed to the strategic interests of the nation.

The Bolsonaro government fiercely fought for its right to cut regulations and environmental protections whenever it could. When the president’s supporters took action by themselves, starting fires to clear the forest, his government dragged its feet in responding, treated environmentalists vindictively and, especially after scientific whistleblowers came forward, slowly defunded and shut down regulatory agencies.

Paranoia is fundamental to the worldview of Bolsonaro, as is natural with a mind that sees the world primarily as a site for conflict. Comparisons with the 45th president of the United States can be overdone, ignoring how Bolsonaro, unlike Trump, descends directly from the lineage of a military dictatorship. But in the paranoid style of their politics, their association with purveyors of that style (the Bolsonaro family are often seen with prominent Trumpians such as Steve Bannon) and most particularly in the persecution complex that haunts them personally, the two leaders really are bound together. Both men are (or affect to be) afflicted by a terrible fear of conspiracy. Both feel that one’s only reliable allies are blood relatives, and both fear that every institution is out to get them.

In diversity, democracy, even science, the Bolsonaristas see only enemies, and enemies to eradicate. The Bolsonaro movement taps into smouldering national anxieties—not least around race, in a society where the legacy of slavery and colonisation has been a taboo subject until very recently—and combines this with generic 21st-century forms of disinformation: QAnon-style internet horrors and flat-earther dominated group chats. Further indignation is stoked around religion and sexuality; Brazil often alternates between very permissive, live-and-let-live liberalism and incredibly conservative, “family values” rhetoric: thriving LGBT scenes exist alongside angry, fire and brimstone evangelical churches, locked in combat on the same streets.

It is hard to spot much consistent ideology beyond the basic bigotry on the fake news feeds of those in the movement: it is not unusual for the president to start saying the opposite of what he had previously insisted on as fact. But there are strong emotional threads, such as the pervasive belief that the modern world hates the righteous, and that only unwavering loyalty to one man can put things right again.

The diagnosis of paranoia is not, incidentally, armchair psychology or guesswork: it’s more or less been heard from the mouth of Bolsonaro himself. In a leaked video of a meeting with his cabinet, the president foams at the mouth about changing supposedly suspect federal police staff: “I won’t wait for my family or my friends to get screwed!” he exclaims. Later, he adds: “I want the people to be armed. An armed people can never be enslaved.”

“Most Brazilians do not ask whether Bolsonaro will try for a coup, but how”

But what has protection by a “strongman” done for the safety of Brazilians? On the day of that outburst, over 1,000 more citizens died in a pandemic that Bolsonaro has greatly aggravated. “Life goes on,” he bellowed to a journalist early on who asked about imposing lockdown measures. “We can’t become a country of sissies!” When he contracted Covid-19 himself, he set the most damaging possible example by discussing it with journalists while unmasked. The upshot is that Brazil’s relatively youthful society (it has a median age of just 33) now has the highest death rate per million of any large country on Earth, with 600,000 lives lost so far.

Before the arrival of coronavirus, Bolsonaro’s air of violence seemed like something that would only really affect “mouthy leftists” or “out of touch” minorities. Its arrival converted his indifference to physical suffering and death into lived reality for many Brazilians. There is now an active scorn for the dead, which fits neatly Umberto Eco’s theory of fascism: death by illness, gasping for breath in a hospital bed where oxygen supplies have often been allowed to run short, is somehow seen as a fitting end for the old and weak. But finally the Senate’s Covid inquiry has allowed a little light in, offering a grim round-up of the government’s actions. Over the past six months it has provided a steady stream of reminders of the callousness and corruption of Bolsonaro’s regime; government officials found ample “opportunities for business” lurking in the pandemic. In late October, the inquiry culminated in the dramatic recommendation by its committee that the president should face criminal prosecution on a slew of charges—including charlatanism, misuse of public funds and crimes against humanity. But so long as Bolsonaro maintains his grip on the levers of power it’s unlikely he will stand trial.

The absolute refusal to accept that the virus was dangerous; the peddling of ineffective medications such as ivermectin as miracle cures; failing to respond to Pfizer’s emails on three separate occasions. Each of these should on its own be a scandal to sink a government. And this is before we get to the genuine horror story about endorsing what amounts to human experimentation: it was discovered that a healthcare provider was running trials on its patients of a Bolsonaro-backed “early treatment” Covid kit without their informed consent. This was—this is—the Bolsonaro era: the laughably absurd and the impossibly cruel walking shoulder to shoulder.

“To hell with our scruples!” said Jarbas Passarinho, one of the dictatorship’s many colonels, in 1968. The outburst is emblematic of the hardening of the regime’s grip on the country. Half a century on, if Bolsonaro has an ethos, Passarinho’s utterance captures it.

It was always hard to believe, given the US’s solid democratic tradition, that Trump could pull off the insurrection he attempted by trying to bully his vice president and others into undermining the electoral process, and egging on the motley crew of protesters at Capitol Hill in January.

But Brazil is a young democracy: those aged 50 and over came of age under dictatorship. Bolsonaro, unlike Trump, lives and breathes in the shadow of military dictatorships past. He has taken an interest in the army while in power. The results have often been chaotic—his firing of the armed force’s ministerial overlord, General Fernando Azevedo e Silva in March prompted the simultaneous resignation of the heads of the army, navy and air force—but the resulting shake-up did his allies no harm.

In looking towards next year’s election, the question most Brazilians ask is not whether Bolsonaro will try for a coup, but how. What will it be? An incendiary even if abortive conversation stopped in its tracks by an even-headed aide, as has happened before? A Trumpian attack on democracy’s mechanics? He’s certainly paved the ground for that: much as Trump himself was stoking baseless fears about postal votes for many months ahead of last November’s election, so too Bolsonaro now questions—and flirts with refusing to accept the returns from—the same voting machines that elected him last time. But maybe it will be something different. Perhaps a rebellion of hardcore followers, escalating from a rally, which might—with luck—be quickly subdued? Or could we instead see, following the 1964 precedent, an outright attempt to summon military power and pit it against civilian authority?

The ultimate prize for Bolsonaro lies in his understanding that Brazilian democracy, once desecrated, will not be made whole again so easily. It has, after all, had to grow up in scar tissue—sometimes literally so. “In a way, it was worse to be young under torture,” Rousseff said, describing her time as a prisoner of the dictatorship. “Because we changed forever. We have to live with it for the rest of our lives.”