It was a dozen years into the war when I visited Camp Shorabak, an Afghan military base attached, like a kind of lean-to shack, to the perimeter fence of the American and British bases in northern Helmand. It was autumn 2013 and I was on a Nato-organised trip that had just visited the town of Lashkar Gah, from which the British Provincial Reconstruction Team was preparing to withdraw (or “lift off,” in their rather sickening official phrase). There, assurances of the success in securing Lashkar Gah were accompanied by a categorical refusal to allow us one foot outside the British wire.

At Camp Shorabak, we were taken to see Nato’s mission to train Afghan soldiers in the use of the new and alien US weaponry that Congress had compelled them to adopt under the influence of the US military-industrial complex. The Afghan officers, unarmed, sat on the ground. The British instructor, with a pistol at his side, stood at the whiteboard, entirely reliant on an unarmed Afghan translator. In each doorway stood a Georgian soldier in full body armour, holding an automatic rifle poised with the safety catch off, the Caucasian nation displaying its eagerness to join Nato through its readiness to shoot our Afghan allies on the spot if they made a move to attack their teacher. If I didn’t know already that the Afghan campaign was doomed, I knew it then.

Graft vs grit

The explanation of the Afghan disaster comes in three parts: the Taliban victory; the government defeat; and the US withdrawal. From the point of view of Britain and Nato, however, what is really important is what the Afghan campaign says about us and our place in the world.

Start with the Taliban victory. As a matter of decency, we must—however distasteful their ideas and brutal their practices can be—acknowledge the extraordinary courage, grit and self-sacrifice of the Taliban in the service of their own cause. We in Britain should have learnt something about the Taliban leadership from our old experience of persistent Irish nationalist militancy. Recall how Yeats summed up its spirit in Easter, 1916:

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream

The “stone” in the case of Afghanistan has been the diehard loyalty of the rural Pashtun Afghans to their own religious and cultural traditions.

For far too long, far too many western officials and journalists convinced themselves of the absurd line that the Taliban was simply a creation of Pakistan without deep roots in Afghanistan, and that their ideology was alien to Afghan tradition—a tissue of lies mixed with small fragments of truth that rendered Taliban resilience and mass support incomprehensible. The most amazing thing about this western propaganda fantasy was that only a dozen years before 9/11, the very same Afghans (or their fathers), from the very same areas, fighting for the very same reasons (nationalism, religion and revenge) had been the darlings of the west, when they were resisting the Soviets and their Afghan communist allies in the 1980s.

If I have long had a sense of knowing the Taliban, it is chiefly because in 1988 and 1989, as a young Times journalist, I made a number of journeys with the Afghan mujahideen. The only significant difference between them and the subsequent Taliban that I can see is that, compared to the mujahideen, the Taliban evolved a vastly more united and disciplined organisation and much better leadership.

As to the rapid collapse of the Afghan state, this might seem more surprising. After all, the communist state left behind by the Soviets when they withdrew in March 1989 lasted for another three years, and only crumbled after the USSR itself collapsed and Soviet aid came to an end. “Our” Afghan state, in unflattering contrast, fell in a fortnight.

But when in December 1979 the Soviet Union came to the aid of its endangered communist allies in Afghanistan, Moscow inherited the old Afghan royal state and army—severely battered and prone to defection, but still performing their old core task of fighting Islamist and tribal rebels. (In a similar way more recently, when the Russians and Iranians successfully intervened in Syria, they came to the assistance of a recognisable existing state.)

This is a big difference with the US after 9/11, which did not concern itself with inheriting any real Afghan state structures at all. The armed groups that had provided the ground forces of the US invasion came from the Northern Alliance, a grouping of ethnic militias and warlords that were hated by many for their previous brutality, oppression, looting and internecine warfare, and often made themselves more hated through their subsequent behaviour. The US had to spend several years reducing their role.

The Americans then made things worse by stubbornly refusing for several years to employ former “communist” officers from the 1980s, squandering their expertise until it was too late—part of a general refusal to accept that there could be any parallels with the Soviet experience, or lessons to be learned from it.

Western aid to Afghanistan, when it did not simply go into the pockets of western contractors, consultants and NGOs, fed an explosion of Afghan corruption. Admittedly, just because this money was stolen it doesn’t follow that it was wasted. Some of it was used by the government to create a patronage network based in Kabul that attached local warlords and chieftains to the Afghan state.

However, by drawing such leaders away from their base, this patronage also undermined their hold on their local followers. The result in recent weeks has been the failure of local ethnic militias to fight hard against the Taliban—totally unlike the pattern of the 1990s. Their commanders were too busy living the high life in Kabul or Dubai on some mix of stolen western aid and heroin money.

The question of closeness (or distance) between commanders and their followers is crucial to the fighting spirit of irregular and semi-regular units, whether on the side of the government or of the rebels. I realised this in 1989 in Islamabad, Pakistan, when I visited “General” Abdul Rahim Wardak, the “military commander” of Pir Syed Ahmed Gailani’s National Islamic Front—who was also living off western aid. Officially, western officials loved this royalist force led by members of the old aristocracy for its “moderation,” compared to the radical Islamist groups. Unofficially, members of the front were known to every journalist, official and spy in Peshawar as “the Gucci guerrillas.”

When I met Wardak he was indeed wearing a beautifully tailored western suit, with a heavy gold watch; but he had not forgotten his military role—there was a camouflage band around his gold pen. The contrast with the tough, impoverished, pious peasant fighters with whom I had travelled in Afghanistan was surreal. Many years later, in 2004, I heard that Wardak had been made Afghanistan’s defence minister—another of those moments when I felt that the west’s efforts were likely to fail.

“Why on earth would any Afghan soldier die for some general’s chance to sit in a Louis XIV-style chair?”

I was vividly reminded of Wardak this summer when I saw BBC footage of the Afghan state’s collapse, showing Taliban fighters posing triumphantly on the gilded chairs and luxurious carpets in one of the palaces belonging to former vice president Abdul Rashid Dostum. Dostum has now fled abroad, but once upon a time he was a notoriously tough and ruthless commander of an Uzbek militia against the Taliban. Now, he had obviously been softened to the point of liquefaction by the corrupting effects of western aid.

There are many questions to be asked about the Afghan state’s collapse, but the plainest as well as the most important is: why on earth would any Afghan soldier want to die for General Dostum’s Louis XIV-style chairs? We will have to see whether Taliban commanders lose what has been their greatest asset, their closeness to the men they lead, by in their own turn becoming corrupted by the chance to sit in such chairs.

Exceptional errors

As to the American withdrawal, that was always going to happen, because every American administration said so, from the very start. Yes, some American generals and security officials liked the idea of keeping permanent bases in Afghanistan to threaten the Iranians, Russians and Chinese. But there was never any chance of the US maintaining a generations-long state-building effort backed by an American army. As long as the Taliban held out and the Afghan state failed to develop, then sooner or later the withdrawal of US power—and the collapse of the strange Afghan state whose whole shape was determined by it—was on the cards.

Perhaps at the very start there was a chance of creating a tenuously viable and consensual Afghan state, if the US had been willing to negotiate and compromise with sections of the Taliban. As described in a brilliant book by a former British officer, Captain Mike Martin (An Intimate War: An Oral History of the Helmand Conflict), this possibility was wrecked at a local level by the ambitions, hatreds and fears of the Pashtun warlords whom we had brought back to power and wealth in eastern and southern Afghanistan.

Naturally unwilling to share their regained power and wealth with former Taliban commanders, our allies made it their business to tell the American special forces that these men were still working for the Taliban. In truth, with its regime apparently defeated for good and its assets and networks displaced, they were often anxious to join the government: I heard this with my own ears as early as the start of 2002, when I visited eastern Afghanistan. And yet the ears of the Americans were open only to the poison that their allies found it advantageous to pour in them: the US army dutifully killed or arrested most of the local leaders in question, bitterly alienating their clans and personal followings.

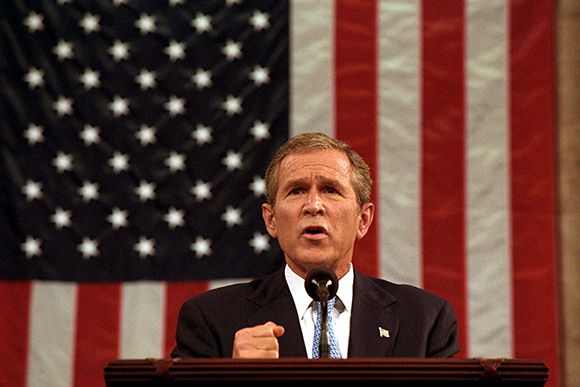

This dreadful error was enabled by another, more fundamental one, set out in president George Bush’s declaration of the global war on terror and deeply rooted in American “exceptionalist” nationalism: the framing of the struggle as one of good against evil, in which “you’re either with us or against us.” No approach was less appropriate to the fluid political allegiances and enduring kinship arrangements of Afghanistan. But it warped the thinking: when I and others in Washington called for talks with the Taliban—for years, until it was too late—we were shouted down with cries of “the Taliban are evil” and “America doesn’t talk to terrorists.”

An alliance of appearances

As far as Britain and the non-American members of Nato are concerned, all of this is in a sense irrelevant. Victory or defeat in Afghanistan did not depend on us, and in any case we were not there—whatever our leaders might sometimes have told us, and maybe even themselves—because of Afghanistan. We were there to please the United States, though for reasons that differed significantly between Britain and the Europeans.

Nonetheless, we owe it to our dead and wounded soldiers and their families to conduct a post-mortem into the reasons for their sacrifice; if a disaster on the scale of Afghanistan does not lead to honest self-examination, then it will expose our political system as abjectly incapable.

As far as most of Nato’s European members who contributed troops to Afghanistan were concerned, this was a theatrical exercise designed to keep the US committed to the defence of Europe. In the case of the Poles and the people of the Baltics, the great spur here was fear of Russia. In the case of the French, it was largely because they can only maintain their sphere of influence in Africa with American help. In the case of others like the Germans, it was because they knew that they were not capable of summoning up the fighting spirit or the military spending to maintain peace in the Balkans and deter Serbian or Turkish aggression there. The memory of Europe’s 1990s failure in Bosnia runs deep.

Across much of the continent, running deeper still are the memories of various disgraces, surrenders, absences (or in the Polish case, doomed last stands) during the Second World War, after which the Americans had eventually ridden to the rescue. The most important thing—perhaps the only important thing—was to keep them engaged. A German official of my acquaintance admitted this candidly. “So as far as Afghanistan is concerned, Germany’s plan is to do the absolute minimum required to keep America committed to European security?” I asked him. “Yes,” was his reply.

For all the real effort they made in Afghanistan, then, most Nato countries involved might as well have performed national dances at US presidential inaugurations to display their allegiance and amuse their imperial protectors. Of course, the Americans can see through this perfectly well. In the biting words of an American officer in Afghanistan about his European allies (he made an exception for British courage, though not British competence), “they pretend to fight, and we pretend to listen to them.” It was thus entirely logical that the Biden administration’s decision to withdraw from Afghanistan was taken without informing Nato, let alone consulting it.

As to Britain, as documented in new books from Philip Stephens (Britain Alone: The Path from Suez to Brexit) and Simon Akam (Changing of the Guard: The British Army Since 9/11), the decision to deploy the British army to Helmand in 2006 involved a real commitment, and a real readiness to fight. It was, however, also taken for reasons that had nothing to do with Afghanistan. The background reason is that Britain’s continuing pretensions to global great power status now wholly depend on the US, with the paradoxical result that in geopolitical matters the British “global power” generally behaves like an American serf. The foreground reason was that Britain needed to regain credit in Washington after the embarrassing failure of the British army in Basra in Iraq (which I have to say was not really their fault, given the mess in which Bush and Tony Blair had landed them).

“The British effort was essentially to put on a performance of military commitment for an American audience”

As described by Akam, there are a number of quite specific reasons for the strange combination of courage and carelessness with which the British army as an institution conducted the Helmand campaign—apart from the fact that self-sacrificing amateurism appears to be an integral part of the British military tradition, something my own Second World War-era relatives used to remark on bitterly.

But it cannot have helped that the chief motive for the British effort was essentially to put on a performance for an American audience: recall how in 2002 Blair confirmed to the BBC that he agreed with Vietnam-era US Defense Secreary Robert McNamara’s view that Britain needed to pay a “blood price” for its relationship with America. (I might partially accept that argument, if Blair and his like had risked their own lives in Helmand.) He added: “they need to know, when the shooting starts, are you prepared to be there?” The great thing was to be seen to be part of the action.

In a sense, therefore, it was as irrelevant to ask a British intelligence officer to learn Pashto as it would be to ask an actress playing Juliet to learn Italian. And if you can’t ask an Afghan soldier to die for some chairs, how do you ask a British soldier to die for a play?

Closer-to-home truths

The result of the Afghan experience will probably be to finish off for the foreseeable future any British—let alone European—willingness to engage in counter-insurgency or state-building operations. And this may contribute to a disaster for Europe that dwarfs Afghanistan; because there are crumbling states closer to home whose downfall could affect Europe much more directly.

I have a feeling that, looking back, historians of the future may see the biggest Nato failure of recent years as lying not in Afghanistan, but in the failure of Nato’s British and European members to live up to their promises to give real help to the French and Americans in supporting crumbling states in western Africa. The British have contributed a dozen planes and a couple of hundred men. Most of Nato’s European members have contributed nothing but hot air.

If states like Nigeria with its population of some 200m people (and set to double by 2050) collapse into chaos due to a mixture of Islamist rebellion, ethnic conflict, corruption, population growth, water shortages and climate change, the result will be a flow of migrants to Europe on a different scale to current Mediterranean crossings. We have seen in Germany and other European countries in recent years how the backlash against migration has been central to the rise of chauvinist parties. By exploiting the kind of numbers that may come from west Africa in future, such parties could potentially destroy liberal democracy in Europe.

Trying to prop up countries in Africa with military support as well as aid is critical to European security in a way that Afghanistan never was. But any chance of success depends on Britain and Europe learning the lessons of Afghanistan: the need for a truly long-term commitment, and a real willingness to suffer losses, and all based on true local knowledge and an understanding of local realities, not western fantasies of building liberal democracy.

These are the sorts of cases that President Biden’s secretary of defense, General Lloyd Austin, alluded to when he suggested (in a diplomatically veiled way) that Britain might help Nato best by concentrating on security threats closer to home, rather than sending an aircraft carrier without aircraft to the South China Sea. (That, of course, is yet another instance of us conducting international relations as an exercise in keeping up appearances.) The greatest tragedy of all for the British dead in Afghanistan may therefore be that they not only died in a play, but went to the wrong

theatre.