I’m with a house reg, which just means he’s not a regular client of mine but of the brothel in general, passed between all of us and light-heartedly mimicked in the girls’ room, his slow sing-song speech driving some of the girls up the wall and lulling others into sleep. I find I am often on the brink of tears with him. Not because of the way he treats me—he is exceedingly gentle and unobtrusive—but because he lives a truly lonely life, the kind that makes me realise why straight people are so concerned with pairing off in their twenties to prepare for their old age. In his fifties but looking like he’s in his eighties, with one lone aunt overseas and his only socialising done in the break room of the accountancy firm where he works, he tells me the same story of his day trip to a coastal town every time he sees me. He only lasts a few minutes.

Afterwards, we lie together and he tells me about how he’s been sleeping in his car because the tenant above him makes too much noise at night and he is too scared to confront him and that his landlord hasn’t been answering his tremulous emails. I feel an intense pathos and know that I—along with the other girls—am probably the most attentive listener he’s had in years. He says it’s his birthday next week and that he’d like to book me for it and I try to show him how to contact the tenants’ union. Then he asks me about dating, and which websites he should find a girlfriend on. He mentions OnlyFans and I steer him away from that, suggesting Plenty of Fish instead. He tells me he has tried it and it is a “fake website.” I assume he means fake images, so I reach for my phone to teach him how to reverse Google image search, when he says: “I know it is a fake website because every woman I message says, ‘I do not want to go on a date with you, you are not my type.’” My heart sinks, because that confirms to me that he’s been messaging real women, and how do I tell him that in most women’s eyes he is undateable? If he were rich, he’d be dateable, no worries. He’s kind and not repulsive and easy to manage. But without the lure of lifestyle or property, he is completely undesirable. And, on top of that, dating is expensive. Its prohibitive cost and the overall politics of desirability are what lead many of my working-class male clients my way.

For example, a young migrant man who has come to Australia by himself and sends much of his money home to his family, who works on a construction site with other migrant men and whose English is minimal. He comes in to see me because one of his colleagues told him that I am “nice and welcoming if you’re nervous” (a recommendation that touches me more than I can say; it is easy enough to be a good fuck, but another thing entirely to craft an atmosphere that people can feel comfortable being exposed in, both emotionally and physically) and $130 is an amount he can afford. Dating in Australia is not feasible for him for a number of reasons, not least the fact that he must return to his home country in a few years—yet why should he be denied intimate touch in the interim?

I believe we all have a “right to touch,” as it’s a basic human need, and for many men socially and culturally the only way they receive that touch is through the space around sex. Not necessarily the sex itself—but the lying naked on a bed with someone, and the incidental touch surrounding it, such as the post-coital leg draped over a hip. (When I say “right to touch” I am not using it in the way that incels use “right to sex,” which is an entitlement they think they are owed—they despise the idea of having to pay for it as a service.) Plenty of affluent elderly women get their hair done once a week for a similar access to touch and intimacy. Like me, I’m sure plenty of hairdressers feel the murky reality of their working relationship with clients, where they may perform a paid touch but feel a real sympathy. There is a shared sanctity in both spaces, a spilling of secrets and an insight into private and personal lives.

In my nine years of doing this work I have seen an increasing demonisation of the clients of sex workers, even while I’ve seen increasing support for sex workers themselves. Much of the discussion around sex-worker rights focuses on the workers, how often marginalised people enter the industry out of financial necessity, and how criminalising that only further marginalises them, by forcing them into more dangerous scenarios and punishing them for their need. All this is of course of pre-eminent importance. And I think that the rights of sex workers shouldn’t rely on the value or respectability of the work itself—it is simply a human rights and labour rights issue. Sex workers should be able to speak about exploitation and abuse in the industry without that being used against us to argue for the eradication of the industry itself—in the same way migrant workers are speaking about working conditions on Australian farms without it leading to a cry to shut down agriculture.

However, I think the blanket demonising of clients does a disservice to both those who pay for sex and those who sell it, for a few reasons. Firstly, it sets up a binary without considering that there are plenty of people who switch between worker and client. This switch is accepted far more often in the queer community (especially among gay men who tend to work more informally, though I too have occasionally had other queer women sex workers book me).

Secondly, it reduces all clients to a stereotype, and assumes they are all cis men. And thirdly, it is a gateway to demonising the sex industry as a whole. The Nordic/Swedish model (also known by the misleading term “asymmetric decriminalisation”) criminalises the buying, but not the selling, of sex. It is championed as pro-women/anti-sex buyer, when in fact it further complicates and endangers the lives of people in the sex industry and anyone dependent on them (whether partner, parents or children). The model makes it harder to screen clients (as they are reluctant to give details when they could be arrested), forcing workers to work in more out of the way places alone (as a fellow worker can be charged with pimping if they work together), and making it virtually impossible to use their income to live stably (as anyone they give money to can be prosecuted for pimping, such as a landlord) amongst other things. And the hatred of clients is used to hate on sex workers; we are dirty by association. How can there be true respect for the labour that we do, when it is seen as despicable to buy? This is similar to the way the condemnation of drug dealers ignores that users and dealers are often one and the same, and that friendships, trust and care can exist in those transactions.

Of course, I understand why some sex workers hate clients. When you are doing this work through economic need, mental anguish and burnout, it is an extremely difficult job—especially when it feels like there is a blatant power imbalance between you and your clients or management. About five years into full-service sex work, I hated all clients because I hated the work and that I couldn’t take a break from it. I was largely doing escorting at the time and my clients were mostly rich white men who I felt held the money over me. I hated that they thought I was “lucky” for getting to do a job where I could potentially orgasm, when all I could think of was, wow, you’ve got a property portfolio and I have to suck your dick to have a stable rental. The interactions between us were reflective of the inequality of the world.

The last four years I have done largely suburban brothel work, in more migrant and working-class areas. I was becoming more financially stable and could afford to take a few days off if I felt burnt out, and I began to empathise more with my clients. I began to get to know them better too, to have regs who approached me more as an equal. A man who lives at home with his elderly parents and can’t date because all his time is devoted to caring for them, yet still manages to practise tying shibari-style knots on the legs of his bed, to use on me later. A homeless man who saves up his coins and comes in once a month, who gets a good shower and bed and fuck all in one. A refugee who spent years locked up in detention, had untold violence inflicted on him by our government and whose family is scattered across many countries. A pensioner whose two treats in life are getting a Thai takeaway once a week and seeing me once a fortnight. An intellectually disabled man who tells me I am “so beautiful—exactly like Robert De Niro with your mole,” who smiled when I couldn’t stop laughing as I sat astride his cock. These are all men who I enjoy spending time with, who I gain pleasure from “servicing.” And I use pleasure here not as a polite euphemism for orgasm, though there are clients I orgasm with. I mean I enjoy my time with them, find it affirming and reassuring in this often terrifying world that I can have genuine moments of connection with people, that we can give that to each other.

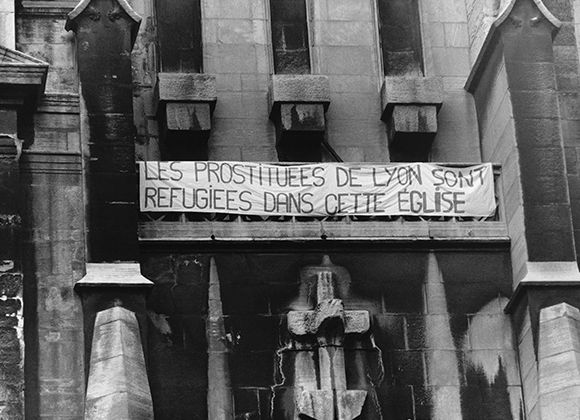

I watched the 1975 documentary The Prostitutes of Lyon Speak recently, which filmed sex workers who occupied the Saint-Nizier church in Lyon in June 1975 to protest violent treatment from police and the effects of criminalisation on prostitutes (an event that is marked every year by International Whores’ Day on 2nd June). I related to one of the women when she said: “The worker on minimum wage comes because he doesn’t have a woman or because he has problems with his wife, if they argued or if she cheated on him or very often because his wife left him… these men wish to justify themselves. With us, they want the tenderness and understanding they might not find in other humans since we are outcasts ourselves… Going up the social ladder, we encounter men who pay more money, asking to do more perverted things, dirty things… it’s an issue of class and culture.”

I don’t quote this to condemn rich men (after all, if you want a very specific service, book a professional!) but only to point out how class affects access to needs, just as race also feeds into desirability and dateability. People feel plenty of sympathy for white women who are single (so much sympathy that it borders at times, frustratingly, on pity) because they are perceived to need touch and tenderness and validation. But the same compassion is not extended to men who are also somehow disenfranchised.

When I used to hear people refer to sex work as rape, I would get upset on behalf of other workers who, like me, had their experiences collapsed into trauma, and whose actual assaults become invisible within that (it also hurts to hear yourself referred to as a “prostituted woman,” which makes you feel small and sick in a way that’s different to how any bad client can). Now I also get upset on behalf of my clients, who are not rapists by virtue of paying for sex, and some of whom I care about deeply. Sure, there are bad clients. They may be bad, for example, because they are knowingly and callously exploiting a power dynamic where they know the other person is unhappy, and are using that to get as much as they can for as little as they can; this is something the wealthy do to domestic labourers often. They are not bad because they are paying for sex specifically.

A relationship is also not inherently bad because it is transactional: we accept transactional relationships often in familial settings (my younger brother only calls me when he needs to borrow money). When it comes to sexual and romantic relationships, however, it is considered wrong for them to be transparently about the exchange of money. (But fine if it’s about the exchange of money with the pretence of romance and the protection of monogamy, such as with trophy wives.) Why is it more despicable for a poor man to pay to fuck me than for a football player to pick up young models at a club, in exchange for access to his wealth and fame?

I feel protective of clients when I read things dismissing them as “sex buyers,” as if they aren’t just normal people who are lonely or horny, as if they aren’t your brothers and fathers and friends and aunties and maybe even you one day. Some of the absolute indignation people express about seeing a sex worker comes from a superciliousness, a “well I would never pay for it” attitude (perhaps because you would never have to, perhaps you’re young and slim and deemed attractive). This is not to say my clients are only people who can’t date—there are plenty who don’t want to date, or don’t have the time to date, which is also perfectly valid. A recently divorced reg who doesn’t yet have the energy for the whole dinner-drinks-texts thing again. All the quick-and-easy young tradies who drop into the knock shop on their way home from work, wiped from a 12-hour workday and looking to relax in someone else’s adept hands. Even those clients I would say I have a friendship with, though I wouldn’t call them friends, because at the end of the day I can’t separate myself entirely from the fact I wouldn’t spend time with them for free, which is fine—they are still people I can laugh and come and enjoy my time with.

So I write this in defence of my clients, knowing that they may never defend me publicly but that’s no reason not to defend them. I understand why people—and especially sex workers who may have had bad experiences with clients—can be pro-sex worker/anti-client, but in the long run it’s not in our best interest. It is an unnuanced view that flattens clients, ignores very real very human reasons why people may seek contact in this way, and imagines us always as the ones on the bottom of the equation. (When a seven-month pregnant woman booked me so she could try lesbian sex before she gave birth and I had one of the most transcendental sexual experiences of my life, feeling privileged to be allowed in to such a significant time of her life, I certainly didn’t feel like the world was rigged in her favour. Would people decry her as a “sex buyer”?) I also want to address the painting of all straight men who access or are adjacent to the sex industry as either punters or pimps—the former being a word that denigrates and homogenises clients and the latter being a direct result of criminalisation, a clear example of a violent system spawning further violence. Having worked for almost a decade in a state with decriminalisation, I can say that pimps are virtually unheard of here.

The pandemic has strengthened my empathy, too, in that being touch-starved for long periods made me realise how acutely someone can need and seek it. Without the loyalty of some regs I would not have made it through financially, and I feel grateful to these men, and hate to think that Sweden would want to lock them up for seeing me (the United States, South Australia and various other places would want to lock me up for seeing them). To me, sex isn’t in a different category to all the other things we can monetise using our bodies. Unless paying for close-contact labour from any person is wrong, how can this be wrong?