In March this year, Vivian Jenna Wilson, Elon Musk’s 20 year-old daughter, posted on Threads that her assigned sex at birth (male) was “a commodity that was bought and paid for”.

“When I was feminine as a child and then turned out to be transgender, I was going against the product that was sold,” she added—implying that when Musk and his then-wife, Justine, used in vitro fertilisation (IVF) to conceive Wilson and her twin brother, Griffin, they used sex selection to choose the sorts of babies (male) they wanted.

With 14 known children (the first of whom, Nevada Alexander, died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, or Sids, at 10 weeks old in 2002), Musk is perhaps the world’s most outspoken advocate of pronatalism, the belief that people should have large families to combat the existential global threat of declining fertility rates.

The US does need more babies. Almost every country does. In 2023, the economist Dean Spears warned that the global population will peak, in the best-case scenario, by 2085; the worst-case scenario has it in the 2060s. That will mean fewer young people to care for an ageing population; to pay into pensions; to advance technology and healthcare.

In 2022, after his 11th child was born, Musk tweeted: “A collapsing birth rate is the biggest danger civilisation faces by far.” He is so enthusiastic about his growing family that he has, reportedly, bought two mansions in Austin, Texas to house his children and some of their mothers. Meanwhile, he frames levels of migration to the US as a threat.

Musk isn’t the only Donald Trump acolyte who is keen on pronatalism. JD Vance used his first speech as vice president to declare that he wanted “more babies in the United States of America”. And the Heritage Foundation, the Washington thinktank whose doorstep-sized manifesto, Project 2025, is thought to be the framework for much of Trump’s decision making, is explicitly pronatalist.

At the same time, Trump, like Musk, has declared himself a fan of IVF. Having referred to himself as “the father of IVF” on the campaign trail (rather ignoring the contributions of Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards, the actual fathers of IVF), in February this year he signed an executive order aimed at “lowering costs and reducing barriers” to parents who want to access the technology.

Before this next part, I should clarify: both my children were conceived through IVF—I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that the technology is one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of the 20th century. Certainly, it’s the closest I have ever come to a miracle.

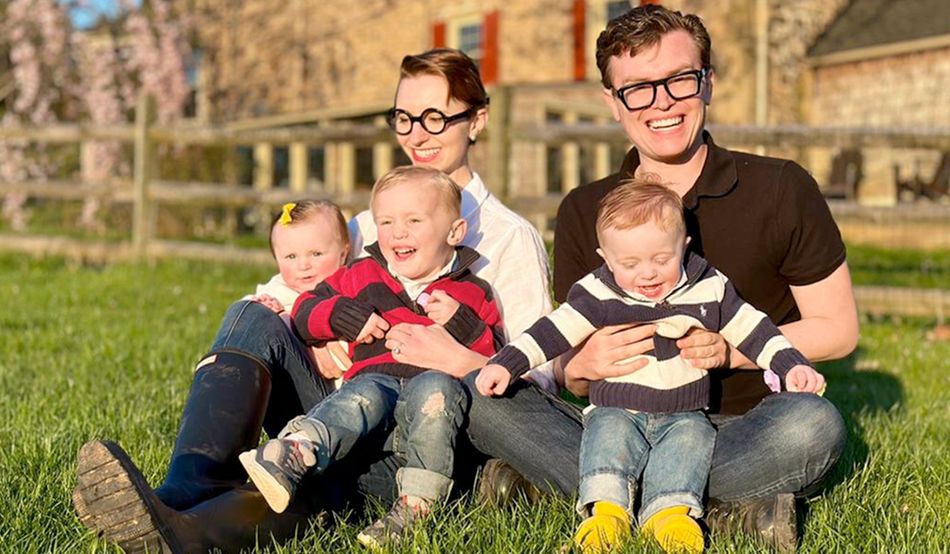

But there’s no escaping the fact that pronatalism and IVF are often mentioned in the same breath. By Trump himself (he signed his executive order because “we want more babies, to put it very nicely”), and by Musk, who has used the technology to produce, by my count, eight of his 14 children. And by Malcolm and Simone Collins, the pro-natalist (and pro-Trump) media power couple best known for giving their children peculiar names such as Torsten Savage and Industry Americus, and slapping his toddler in front of a shocked journalist. The Collinses have even said they screen their embryos for IQ.

Pronatalism is an ideology aimed at solving a looming global crisis, and IVF is a form of medicine, designed to combat a very private grief. Trump’s decision to use one to deliver the other is unsettling. But for as long as IVF has existed, there has been discomfort around it.

In 1974, James Watson—of Watson, Crick and Franklin, the scientists who discovered DNA—told a Congressional committee that a successful IVF pregnancy would lead to “all sorts of bad scenarios”. He added: “All hell will break loose, politically and morally, all over the world.” What, exactly, those “bad scenarios” would be are consigned to history, but others in the anti-IVF camp tended to invoke God, or at least Pope Pius XII, who in 1954 complained—according to a report in the New York Times—about those who “take the Lord’s work into their own hands”.

Still, the first IVF baby, Louise Joy Brown, was born in 1978 (all hell did not break loose, unless you count what happens when one of my kids touches the other’s toys). Since then, more than 10m babies have been created using the technology.

Spears argues that, as the size of the human race increased over the past 200 years, it made “profound advances”: antibiotics, the lightbulb, “video calls with Grandma”. As the population decreases, so too will progress: “In a world with fewer people in it, the loss of so much human potential may threaten humanity’s continued path toward better lives.”

Trump claims it’s this—the need for more babies—that is driving his desire for more accessible IVF. The language of the executive order itself says differently. The order requires that Trump’s team provides ideas to reduce the cost of accessing the technology within 90 days (a deadline of 19th May)—but it also makes a clarification. Those ideas, it says, should be aimed at helping “loving and longing mothers and fathers” to have children.

Given Trump’s alliance with the Christian right, and his administration’s views on LGBTQ+ people, these words exclude hundreds of thousands of potential families. Kimberly Mutcherson, a professor at Rutgers Law School who focuses on reproductive justice, bioethics and family and health law, puts it bluntly: “I am a black queer woman in the United States. The folks who are so concerned about not having enough babies in this country are not concerned that I am not having enough babies.”

You can see why Trump and his team like IVF. It won’t just help them make more babies—it also offers control over the sorts of babies that will be created. That control is what Musk presumably wanted when he selected his daughter Wilson’s embryo; it’s what the Collinses appear to want when they screen their embryos’ IQs (although the efficacy of the technology behind that is heavily disputed); it’s what the Heritage Foundation wants when it repeatedly promotes marriage between “one man and one unrelated woman”.

“There are people who say, ‘Yes, we need more people in the world—but we need more of certain types of people in the world.’ And IVF allows you to exercise that control,” says Mutcherson.

It’s easy—and entirely appropriate—to draw parallels with eugenics, particularly given pronatalism’s storied history with the practice. (Nazi Germany, for example, encouraged “racially pure” women to bear as many children as possible.) If the US did introduce rules governing what sorts of children can be born through IVF, however, it wouldn’t be unusual. Dozens of other countries do this already.

In the UK, rules around a woman’s age, body mass index and even the length of time she has spent with her partner govern whether she can access NHS-funded IVF. In Italy, only heterosexual couples are allowed to do IVF. I myself am a eugenicist, it turns out: when I did IVF, I used genetic testing to screen my embryos for a genetic condition my husband carries. In essence, I used technology to select the baby I didn’t want to have—and I did it on the NHS. “That is a definitionally accurate form of eugenics, for sure,” John Appleby, a lecturer in medical ethics at Lancaster University, tells me.

IVF was conceived (forgive me) as a solution to a healthcare problem. By limiting the types of people who can access it, IVF becomes a “mechanism to fulfil a political agenda or ideology,” says Stephanie Jones, the founder of the Michigan Fertility Alliance and a fertility and family-building advocate. For Trump, there is a tension between these things. Because although the likes of Vance and Musk favour IVF, and polling by the Pew Research Center has found that 70 per cent of Americans believe it is a “good thing”, one of Trump’s most loyal supporter bases—the pro-life movement—are not necessarily fans.

In February last year, a ruling by Alabama’s supreme court effectively outlawed frozen embryo transfers. Pro-lifers celebrated. Freezing embryos is a common practice in IVF: instead of releasing one egg, as women do during normal ovulation, drugs are used to make a patient’s ovaries release multiple eggs (sometimes dozens) in one go, allowing doctors to create multiple embryos. These embryos are usually cultured for five days. Any five-day old embryos—known as blastocysts—that survive at the end of this process are either transferred into the patient’s uterus, or frozen.

From egg collection to blastocyst stage, there’s a huge attrition rate. I’m a good example of this. In the cycle of IVF I did, we collected 21 eggs and made 14 embryos. By day three, 11 were still alive; six survived to day five. One was found to be a carrier of my husband’s genetic condition; one transfer didn’t work; the next two did. I now have two live children and two frozen embryos.

What happened to US abortion rights offers clues as to what might happen to IVF

Pro-life campaigners, though, believe that life begins at conception. By their logic, frozen embryos are, effectively, abandoned children. After Trump signed his order, Lila Rose, the president of the pro-life group Live Action, who has previously offered him plenty of praise, posted angrily on X that “IVF is not pro-life”.

How does Trump resolve the tension between his pronatalist acolytes and pro-life voter base? What’s likely, says Mutcherson, is “a reconciliation” between these camps. She envisages a scenario in which, for example, the federal government could introduce a ban on frozen embryo cycles, forcing doctors to collect just one egg in every cycle (a practice now marketed by pro-lifers as “ethical IVF”). Or, it could enforce a rule by which would-be parents are mandated by law to use all embryos created in a cycle, or unused embryos must be passed on to another couple, known as “embryo adoption”. These solutions would suit the pronatalists as much as it would the anti-IVF camp.

Trump may want “more babies”, but he has so far not signed any executive orders making it easier for most Americans to have or raise babies. The US’s maternal mortality rate is the highest in the developed world, and it ranks lowest for parental leave and highest for childcare costs in the OECD.

Since Trump’s executive order, when I speak to fertility experts or campaigners, I have started to ask a seemingly outlandish question. Is there a scenario, I ask, in which IVF becomes a tool by which the administration can force a pronatalist agenda? So that if, for example, you haven’t had children by a certain age, you can be made to freeze your eggs?

Not everyone I ask thinks it’s that far-fetched. Nikki Zite, for example, is an obstetrician-gynaecologist in Knoxville, Tennessee—a state with strict anti-abortion laws—and the vice chair of education and advocacy at the University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine (though she makes clear that her “comments are my own and do not represent those of my institutions”). She says: “I have stopped thinking any scenario in personal reproductive healthcare is too dystopian to potentially happen. We are living in a time when people are losing their ability to decide when and how to start their families.”

What happened to US abortion rights offers us clues as to what might happen to IVF. Abortion and IVF are two sides of the same coin, after all. When IVF goes wrong, which it does in more than one in five IVF pregnancies, the procedures and medications used to ensure it goes wrong safely are identical to those used in abortion. The erosion of rights around abortion happened slowly, and then all at once, with the overturning of Roe v Wade in 2022. Most likely, says Jones, the founder of the Michigan Fertility Alliance, the same thing will happen to women’s rights around IVF. Karla Torres, senior counsel at the Center for Reproductive Rights, tells me that US policymakers who are against abortion “will not stop at banning abortion or undermining IVF in their effort to control people’s reproductive choices”.

IVF, like most technology, isn’t bad in itself. But once it becomes a tool of the pronatalist agenda, IVF will cease to offer families who yearn for children that precious, private joy for its own sake. Instead, it will become a mechanism to apply pressure on women: to stay home, to nurture, to procreate.