The day our lives changed forever we were on the Dorset coast, on our first family holiday since Dad had turned 65 and retired. Cold waves hit warm skin, smooth green hills sloped gently into the gleaming water, my little niece scampered in the sand, the dogs dashed into the waves, and Dad was happy, as he always was when we were enjoying the countryside together.

My two brothers and I were brought up to love the outdoors. In our family albums the three of us peer through mist on top of mountains, cling to the side of cliffs, perch proudly on bikes, plunge oars into winding rivers. The adventures continued into our thirties. But that day, after swimming, Dad couldn’t catch his breath. His oxygen levels plummeted; Mum called an ambulance.

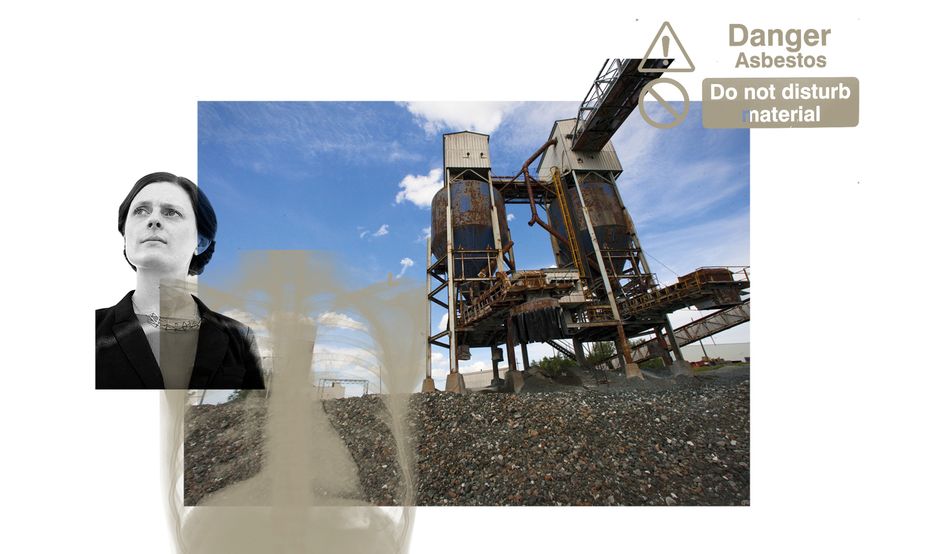

In the hospital he was asked over and over what he’d done for a living and if he’d worked with asbestos. There was not yet an official diagnosis, but there were rumblings of a disease called mesothelioma, a terminal cancer that usually affects the lining of the lung, sometimes the stomach or occasionally other organs. It is almost always caused by asbestos.

“But what would I do without you?” Mum’s question was sincere. They’d met on a Putney tennis court as teenagers and married in their early twenties. The next four decades were hectic with child-raising and work, but I remember how much laughter they shared. There was no laughter that day. Most mesothelioma patients are dead within a year of diagnosis, many within eight months.

We were baffled. The time between exposure to asbestos and mesothelioma symptoms varies widely, from the typical 30 to 40 years to as few as 10 or as many as 70. But historically that link has been easy to identify. The typical mesothelioma patient was a retired industrial worker with clear asbestos exposure. Dad had been an accountant.

I had only the haziest understanding of asbestos as some dangerous substance used in decades past. But as I cared for my father, I learned how it came to be ubiquitous in our infrastructure. How it was blended into cement, vinyl floor tiles and insulation; car brake linings and gaskets; household products from mattresses to dishtowels. The list could go on and on. And it did go on and on, for long after its dangers were known.

Asbestos is thought by many in the UK to be a problem of the past. Anti-asbestos campaigners fought corporate coverups and government inaction for decades, and eventually secured a total ban in the UK in 1999. The UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) says that the number of asbestos-related annual deaths—currently at least 5,000 including 2,500 from mesothelioma—will soon fall, as the impact of the ban finally materialises. In other words, the important fights have been fought and mistakes corrected. My father was a character in the epilogue of an old story.

But activists are still fighting a billion-dollar industry that is backed by a powerful and often ruthless lobby with operatives acting globally, including in London. Worldwide consumption of asbestos has declined from two million tonnes in 2000 to 1.3m tonnes today, but it remains big business. It is still produced in Russia, Kazakhstan, China and Brazil. Consumption is mostly in Asia, particularly China and India.

Asbestos remains in most UK schools and hospital trusts, and likely in more than 1.5m houses and flats—though the true number is unknown. Mesothelioma victims in the UK are increasingly likely to be teachers, nurses, musicians and accountants—like my dad—who are contracting the disease after working in crumbling, asbestos-filled buildings. Victims continue to confront illnesses that are impossible to cure, difficult to palliate and entirely preventable.

Asbestos is a fibrous mineral found in the earth’s crust on every continent. For millennia, it has been prized for its resistance to heat and corrosion. According to legend, Charlemagne, the first Holy Roman Emperor, amazed banquet guests by tossing an asbestos tablecloth onto the fire, which was then retrieved unharmed. In the Middle Ages, scammers are said to have sold fragments of asbestos as pieces of the cross on which Jesus Christ was crucified. Around the same time, scholars debated whether asbestos was made from the salamander, a creature able to withstand high temperatures, or if the salamander was made of asbestos. The word itself derives from the Ancient Greek for “unquenchable” or “indestructible”.

The modern asbestos industry began in the 1850s and grew with industrialisation. Steam engines, blast furnaces and mass production required the strength and heat-proof properties of asbestos. Even then, there was evidence of its harm. In 1898, factory inspectors in the UK identified the “evil effects” of asbestos, and said the danger to workers’ health was “easily demonstrated”. By 1918 many insurers would not offer life cover to asbestos workers.

In 1924, 33-year-old Nellie Kershaw, who had worked at a Rochdale asbestos factory spinning raw asbestos into yarn, was the first person whose death was officially attributed to asbestos. She died of asbestosis, a disease caused by prolonged exposure to the substance. The illness varies in severity, but at its worst causes extreme breathlessness and an incessant and bloody cough that allows no rest, day or night. It is often debilitating and sometimes fatal.

The prevalence of asbestosis among textile workers prompted a government inquiry. A 1928 report and a followup in 1933 said asbestos workers who toiled in dusty conditions were unlikely to survive 10 years on the job, and none who had worked there since leaving school would reach 30. In the UK, the report led to regulation on acceptable levels of dust, medical surveillance and compensation, but no plans were made to reduce asbestos consumption. “Chemicals and oils had been causing industrial cancers in European workers since the late 19th century,” write Geoffrey Tweedale and Jock McCulloch in their book Defending the Indefensible. “[I]ndustrial diseases and deaths were readily accepted and absorbed by a system that regarded them as an inevitable and necessary by-product of industrialization.”

Global consumption soared during the Second World War, when asbestos was used in armaments manufacture and shipbuilding. So essential was it to the war effort that the British government temporarily took over asbestos manufacturer Turner & Newall (T&N) to guarantee supply. After the war, asbestos became the mineral of victory and safety. It became a desirable material not just in manufacturing but in buildings and household products too. Asbestos became the mineral of the future.

As a historian of environmental contamination, Jessica van Horssen is not easily shocked. She knew, for example, that the American asbestos company Johns-Manville hid workers’ own health records from them. The company, which would file for chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1982, before reorganising a few years later, had a large mine in Quebec, Canada—the Jeffrey Mine, in a town which was then called Asbestos. To defend against reports that asbestos was making British factory workers sick, which threatened their business, they said these illnesses were caused not by the mineral itself but by the extreme dustiness of the factories or contaminants in the asbestos. Its own exceptionally pure form of asbestos and working conditions were safe, it claimed. For this argument to stand, its Jeffrey Mine workers had to appear healthy.

Internally, the company was in a panic and wanted to develop its own understanding of the dangers of asbestos without their workers or the public finding out. In the early 1930s, Johns-Manville had set up a clinic, which evolved into a hospital in the 1940s, ostensibly to care for workers. Company doctors did not tell their patients of any concerns, but reported instead to their bosses in New York. This was justified as kindness: “As long as the man is not disabled, it is felt that he should not be told of his condition so that he can live and work in peace and the Company can benefit by his many years of experience,” wrote a company doctor in an internal memo. “Should the man be told of his condition today there is a very definite possibility that he would become mentally and physically ill, simply through the knowledge that he has asbestosis.”

The company also funded the Saranac Laboratory, an occupational health research facility in upstate New York, on the condition that they would control the publication of any research findings. The director of Saranac, a scientist called Leroy Gardner, conducted experiments on mice so the company could understand what levels of asbestos dust might be safe. Instead, in 1943, he accidentally discovered that asbestos not only caused asbestosis, but lung cancer too. He suggested the experiment be repeated, but died three years later, and his findings were effectively buried. Scientific proof that asbestos caused cancer would not be published until 1955.

This was the background to Van Horssen’s discovery in 2008 that, between 1944 and 1958, Johns-Manville secretly removed the lungs of between 55 and 75 Canadian asbestos miners who had died in the company hospital. The company lawyer, Ivan Sabourin, smuggled the lungs in his car and drove across the border to the Saranac Laboratory. If there was a safe level of asbestos dust to be found, it was clear these workers had not experienced it, for embedded in their lungs were vast amounts of asbestos fibres. Johns-Manville buried the finding and told families the company did not conduct autopsies, precluding many compensation claims. “That shocked me,” Van Horssen told me. “It was profoundly cynical.”

The current theory is that inhaled asbestos fibres are neither expelled nor broken down by the body

In the late 1950s, epidemiologist Chris Wagner was researching asbestosis and lung cancer around the asbestos mines of South Africa when he discovered an epidemic of previously little-known tumours called mesotheliomas. He published his research in 1960, and presented it at a major conference on the biological effects of asbestos in New York in 1964.

Scientists still don’t know how asbestos causes mesothelioma, but the current theory is that inhaled asbestos fibres are neither expelled nor broken down by the body. Over time, they are thought to damage DNA, promote abnormal cell repair and alter chromosome structure. While asbestosis only develops with extended exposure to asbestos, mesothelioma can develop after far less. Asbestosis was an asbestos worker’s disease; mesothelioma was a wider threat.

At the conference, Molly Newhouse, a London-based epidemiologist, demonstrated mesotheliomas among people who lived near an asbestos factory; Irving Selikoff, a New York doctor, proved the link between insulation work and mesothelioma; Wilhelm Hueper, an American cancer expert, emphasised that groups previously considered safe—from repair men to lab technicians and office workers—were at risk.

All the assumptions about asbestos collapsed. Asbestos diseases were not a result of working conditions but the dangerous nature of asbestos itself. It was dubbed “killer dust” by the media. The horrific nature of the disease added to the panic. As one doctor put it, “[Mesothelioma] is perhaps the most terrible cancer known, in which the decline is the most spectacular, the most cruel.” Victims literally suffocated to death.

By the end of November my own father was suffocating. He coughed almost constantly, and a simple walk around the block for fresh air was a struggle. He monitored his oxygen levels every few hours. It was eerily reminiscent of his pre-illness practice of monitoring and recording his heartrate and blood pressure after his morning run with Amber, the family Alsatian. Now his statistics only declined.

Little progress had been made in mesothelioma treatments until just a few weeks before his diagnosis, when a breakthrough immunotherapy was made available on the NHS. Immunotherapy helps the immune system recognise and attack cancer cells. It tends to be better tolerated and response to it more enduring than with chemotherapy, which is a blunter instrument. It can work well, with some patients surviving years rather than months. But on average, it boosts survival by just one and half months, and for many it makes no difference.

The week before Christmas, I accompanied Dad to his pre-treatment blood tests. He was so desperately weak by then that the nurse let him rest in the blood test chair. It came as no great surprise when the specialist told him the treatment had failed. The cancer had grown fast and wrapped itself around his lung. Chemotherapy remained an option but, like the immunotherapy, was more likely than not to fail, and success would likely only mean a few more months. The doctor said declining treatment would be a reasonable choice. “No,” he said, gasping for air, “let’s attack it.” The doctor nodded. She recommended we get in touch with the hospice, nevertheless.

After the discovery around 1960 that mesothelioma was linked to asbestos, consumption still rose, peaking late in the following decade. The industry continued to insist that asbestos was not a risk beyond factory walls; governments believed it. “Half a century of world research has revealed absolutely no credible evidence of risk to the general public,” read a 1976 leaflet published by a British asbestos lobby group. Asbestos in buildings was “locked in” by concrete and the fibres would not be inhaled by anyone, it was said.

A cornerstone of the industry fightback was what McCulloch and Tweedale call the “chrysotile defence”, which played on the geological differences in the three most common types of asbestos: crocidolite, amosite and chrysotile, also called blue, brown and white asbestos respectively. It conceded that blue and brown asbestos, mined in South Africa, might be dangerous, but white asbestos, mostly mined in Canada, was not. As evidence they pointed to the fabricated lack of asbestos-related disease at the Jeffrey Mine.

The argument was promoted through a slick international network of lobby groups. In the UK there was the Asbestosis Research Council, funded by T&N, Cape Asbestos and British Belting & Asbestos; in the US there was the Asbestos International Association, set up by Johns-Manville and others; and in Canada there was the Quebec Asbestos Mining Association. More than 100 such associations were created.

Governments in the US and Europe fell for it. Demand for South African blue asbestos plummeted, while the white asbestos industry survived, and for some years, thrived. The British government implemented a voluntary ban on brown and blue asbestos from 1968 and a full ban in 1985, but allowed the import of white asbestos until 1999. McCulloch and Tweedale marvelled at the success of the cynical strategy, “since there was nothing in the pathbreaking research [in the 1960s] …to suggest that chrysotile [white asbestos] is benign.” The scientific consensus today is that white asbestos may be less dangerous than blue and brown, but all are category one carcinogens for which there is no known safe dose.

In 1995, updated figures showed the UK was heading for at least 200,000 deaths, not peaking until 2020

Nancy Tait, whose husband died of mesothelioma in 1968 after exposure to asbestos as a telephone engineer, did not believe the industry’s defence. Tait expected there would be many more like her husband who would die from exposure to asbestos in buildings. Armed with just a school education, she became a self-taught expert in asbestos diseases and convinced an east London hospital to help her profile their mesothelioma patients. Her results showed that all had been exposed to asbestos, but none had worked for the asbestos industry. They’d been plumbers, housewives and mechanics, a school building inspector and a teacher. Electron microscope analysis of the lungs of an office worker who died from mesothelioma showed the same type of asbestos fibre that had been sprayed onto her office ceiling. Wives died after breathing in asbestos fibres from the clothes of their dockworker husbands. A woman who laid her coat on her sleeping son during cold winter nights on her return from work at an asbestos factory in Leeds did not know she was killing him. He died in 1988, aged 43, from mesothelioma.

Tait also saw mesothelioma in people who had only been exposed to white asbestos. She was ahead of her time when she insisted: “The dangers of white asbestos are seriously underestimated in this country. Too often one hears from industry, local authorities, fire prevention officers, unions, general practitioners, contractors… ‘it is only white asbestos’.”

She and trade unionist Alan Dalton believed these deaths were foreshadowing a public health catastrophe. Dalton stressed the future danger from asbestos in Britain’s crumbling hospitals and housing estates. Tait argued for a nationwide register of asbestos that could be consulted by construction workers, who she believed were particularly at risk.

The industry derided Tait’s “uncompromising and extremist stance” and a government consultant criticised the value of her research. Industry continued to insist that asbestos outside factories was safe, and a 1985 report by HSE, the regulator for workplace safety, said that indirect asbestos exposure in buildings would amount to perhaps one death a year. The report would help us “continue to live with asbestos”, HSE concluded.

Fewer people worked in asbestos factories by the mid-1970s and so, if the government was right, mesothelioma deaths should have peaked by the 1990s. In 1995, updated figures that at last took account of risk outside industrial settings showed the UK was heading for at least 200,000 deaths, not peaking until 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic interrupted statistics, but analysts expect the next lot of data, which is to be released this summer, to show a decline. There are no projections on the rate of decline past 2030.

On the risk from asbestos in the infrastructure, including from white asbestos, Nancy Tait was right all along.

Three days before Christmas, Dad started chemotherapy. Miraculously, it did shrink the tumour. In January he helped me take down the Christmas tree and sweep up the pine needles. In February he went out for coffee with Mum, something they’d just started doing together before he got sick. After decades of being so busy, they’d finally had a bit of space to enjoy themselves in simple ways.

The improvement was short-lived. The infernal cough returned with a vengeance. Sometimes he coughed until he vomited. As I tidied up around him to prepare for the old friends and colleagues who would come to say goodbye, I realised he’d had his bag of cycling equipment tucked next to him all year. I asked if it was time to put it away. He nodded and I put it under the stairs. By early summer he was using a wheelchair, and soon after bedbound, a sack of paper-thin skin and jagged bones. His blue eyes bulged like he was being strangled by an invisible ghost.

It was a bright summer day when he was transported to the hospice and said goodbye to the home he’d lived in for 40 years. The room in the hospice was nice. It was on the ground floor, with big patio doors that we opened to let the breeze in. His eyes were closed most of the time. My brother visited from Germany with his family; my three-year-old niece whispered to him and drew him pictures.

A week later, he opened his eyes wide and asked my mum, “Do you mind if I die now?” Apparently, it is not uncommon for the dying to ask for permission. “We’ll miss you enormously,” Mum said. “But you’ve done such a good job looking after us and we can take it from here. It’s okay if you rest now.” The next day he fell into an unresponsive state, with the gap between his breaths becoming wider and wider. Mum and I held his cold hands. “He can tell you’re here,” the hospice nurse said. “He looks happier.”

She let us be alone, but poked her head round the door every so often, expecting him to have died. But he just kept breathing. Later, I would sob in her arms. I would walk softly through the patio doors, my vision distorted with tears, to call my brothers. But just then it felt like he would just keep breathing forever. He was so damn determined to live.

It seems fitting that when asbestos was finally banned in 1999, the legislation was passed during the sleepy month of August, when parliament was in recess. Nobody rushed to address the consequences of decades of negligence. Britain was left with hundreds of thousands of buildings containing asbestos, including most schools and hospitals. No guidance was given until 2002, when the control of asbestos at work regulations said asbestos should be left alone unless damaged. A quarter of a century later, this advice remains.

Campaigners called for better public communication on the dangers of asbestos, particularly in schools, but they were told by the Labour government of the time that they did not want to cause panic. More recently, campaigners have been calling for removal of asbestos, starting with schools and hospitals. The previous Conservative government rejected this on the basis that removal would release asbestos fibres and be more dangerous than leaving it in place. Campaigners say waiting for asbestos to fall into a state of disrepair before removal means waiting until asbestos becomes dangerous, by which time it is too late. The risk of leaving asbestos in place, is “grossly underestimated in this country,” says Liz Darlison, a nurse and CEO of Mesothelioma UK, a charity.

Schools must be prioritised for asbestos removal, says Charles Pickles, an asbestos consultant turned campaigner. As a consultant he would receive calls every day from school caretakers, often after a child had run into or kicked a ball at an asbestos wall. He expects there are many more cases that were never reported. Exposure to asbestos as a child is statistically more dangerous than as an adult. “My clients are getting younger,” asbestos lawyer and partner at Leigh Day Harminder Bains told British MPs last year. “I’ve got a 20-year-old who was exposed at school. He is going to die... You need to do more.”

Regular asbestos air monitoring in schools would be a start, activists say. But demands often land on deaf ears. “I constantly feel I’m up against the ballast of the state,” says Pickles. “Sometimes I want to just stand in the street and scream,” says Darlison, who has been campaigning for decades for the government to face up to the threat from asbestos in the UK.

Instead, Darlison and her nursing colleagues founded the Mesothelioma UK Research Centre at Sheffield University to gather their own data. Their own caseloads suggested that government figures dramatically underestimated the number of annual health and education worker deaths. The Sheffield data proved it. Office of National Statistics (ONS) data shows seven healthcare worker deaths each year; Mesothelioma UK’s data shows 65. ONS data shows 23 education professionals die each year; Mesothelioma UK says it’s 70.

The discrepancy is at least in part because the ONS only records the deaths of teachers in schools, and nurses and doctors in hospitals, overlooking many others who work in those buildings, such as porters, cooks, cleaners and teaching assistants. It also includes only the last occupation before death, omitting people who changed career. Finally, the official data does not record the occupations of people older than 74 whose deaths were caused by mesothelioma. In all, campaigners say, government data is not fit for purpose.

The data is even poorer beyond schools and hospitals. The HSE estimates that “at least 300,000 business premises, within a range of 210,000 and 410,000” likely contain asbestos, admitting that the numbers remain “highly uncertain”.

Activists want a national asbestos register, which should be centralised, digital, transparent and public. Pickles suggests an electronic database akin to the nationwide energy performance register, which gives buildings an energy efficiency rating and is easy to understand and publicly available. A register would also allow asbestos to be a central consideration in the upgrades to a crumbling public estate necessary to hit national climate and energy goals. The current regulations and transparency are dreadful, he says, compared with all other types of building compliance.

In 2017, Harminder Bains ran through the streets of London with a court injunction in her bag. She’d received a tipoff that a trove of historic internal documents from Cape were about to be destroyed. The company, which was taken over by French firm Altrad that year, had been one of the largest asbestos companies in the world, with mining interests in South Africa and factories in Britain. It produced asbestos boards until 1980. A group of insurance companies took Cape to court in 2017 to claw back some of the money they’d had to pay to victims of asbestos diseases over the decades.

Before judgment was given, the parties confidentially agreed to destroy the significant documents, so they would never come into the public domain. Bains believed they needed to be saved. She suspected that the documents probably contained evidence of a longstanding coverup: that Cape had known for decades the extent of the toxicity of their products, which included Asbestolux sheets, used widely for building insulation. Cape enlisted a large team of lawyers while Bains had only one colleague, worked pro-bono and balanced a busy caseload. But three years later, she won and finally saw the documents.

She tells me she was “sickened” at their contents. The documents revealed that, in 1969, Cape’s medical adviser accepted that mesothelioma could be caused by “short and possibly small” exposure and that “no type of asbestos proved innocent”. Yet for years the company continued to insist on their products’ safety.

Company data showed that workers handling asbestos boards would release far more fibres than the company admitted. For decades Cape refused to add a warning label, even encouraging Johns-Manville to do the same. “If there had been proper warnings,” a builder who used the materials said in court documents, “I would have taken this very seriously… I would have raised this with Architects and sought the use of other products.”

Revulsion is something Bains has had to get used to over her decades-long career in asbestos litigation. In 2016, she received a call warning her to freeze all contact with a man called Robert Moore, whom she’d been introduced to as an asbestos campaigner and documentary filmmaker. She’d spoken to Moore only in a professional context, but she knew he was close with activist Laurie Kazan-Allen, who had founded the British Asbestos Newsletter in 1990 and the International Ban Asbestos Secretariat in 1999. For four years, Moore had been a close friend to Kazan-Allen and her husband, even offering to shop for her when she had a heart attack.

When Bains was told that Moore was a spy, she laughed. But the tip was real. Moore had been enlisted by K2 Intelligence on behalf of clients linked to the Kazakh asbestos industry to spy on the international asbestos activist network, with a special focus on Kazan-Allen. She and five other claimants won their civil case against K2 intelligence in 2018, whom they sued for damages. The experience left her shaken, humiliated and panicked about the welfare of her international network of activists.

Death from mesothelioma is not considered a natural death, and like all other “violent and unnatural deaths”, an inquest is required. Inquests for mesothelioma are normally “read-only”, meaning there is no official dispute over the key issues. Attendance for bereaved families is optional. It usually only takes about half an hour and there is no jury.

I attended my dad’s inquest on behalf of my mum and brothers. The coroner read out medical reports and a pen portrait, and ruled that my father died from industrial disease mesothelioma, likely a consequence of his time as an apprentice accountant, where he was required to do manual tasks outside of his job description, such as sanding down walls and clearing out the basement. “Were he given safety equipment for this work, he likely would have worn it,” the coroner said, citing my father’s rule-abiding nature and dedication to his health. “He had every right to be furious.” The hearing was not as difficult as I had expected. Our day in court felt dignified and appropriate.

A coroner’s decision does not necessarily lead to a successful compensation claim. Corporations have historically shirked responsibility for asbestos exposure. In the US, for instance, asbestos companies spun off compensation liabilities into shell companies, which then declared bankruptcy. It is a strategy known as the “Texas Two Step”.

Pharmaceutical firm Johnson & Johnson is fighting more than 60,000 lawsuits brought by people who claim exposure to asbestos in talc-based Johnson’s Baby Powder products, which they say caused them to develop ovarian cancer or mesothelioma.

Talc is a mineral often found near asbestos in the ground. Internal documents show that the company found asbestos fibres in their talc at least as far back as 1971. The company is now trying to spin off its liability for talc settlements and jury awards to a new subsidiary company that will be declared bankrupt. Johnson & Johnson says this will help the speedy resolution of the situation. It denies that there has ever been asbestos in its products.

In 2023 it tried to sue Jacqueline Moline, the chair of occupational medicine at Northwell Health, a nonprofit US healthcare provider, for a scientific paper she published concluding that exposure to asbestos-contaminated talcum powder products can cause mesothelioma. The case was dismissed in July 2024.

I used to joke that I had “asbestos hands”, because I was able to grasp a scalding cup of tea without burning them. I don’t say that anymore. But I do believe that the saying is revealing about our cultural relationship with asbestos, which became inextricably linked with the idea of safety during the war. Perhaps, even after all the people it has killed, some trace of its association with safety remains, at least enough to dilute some of the horror of the situation we find ourselves in.

In his book Asbestos: The Last Modernist Object, Arthur Rose shows how the symbolic power of asbestos has evolved with overlapping and sometimes contradictory meanings. In the early 1900s, when it was seen as the material that would facilitate the future, it appeared in utopian fiction. In the 1920s, the modernists used the symbol of the asbestos curtain to demonstrate the artificiality of narrative; the curtain may fall, but the story never ends. In the postwar period, asbestos morphs into a symbol of mass production and the disappointing dreariness of modern life. In some ways, Rose tells me, after asbestos was banned, it “became something we could cognitively relegate to the Cold War era, along with all the other great scares of that time”.

But the asbestos story never really ended, either in the UK or the wider world. Canada continued mining chrysotile—white asbestos—until 2012; in 2004 and 2011 it prevented the UN’s Rotterdam Convention from adding chrysotile to its list of dangerous minerals. Meanwhile, Canada removed asbestos from its own parliament, for safety reasons.

The US did not ban white asbestos until 2024, and many fear what will happen to the ban under Trump, who in 2005 said that many people thought asbestos was “the greatest fire-proofing material ever made”, and in 2012 tweeted that the Twin Towers would have survived if the asbestos had not been removed. In fact, the Twin Towers did contain asbestos, and there has been an increase in asbestos-related cancers among first responders and residents near Ground Zero. The chrysotile defence is still used around the world. The UK will never get rid of all the six million tonnes it imported and used before the ban. Even when asbestos is removed, it is buried and must be continually monitored for leaks.

The fight goes on. It is often dangerous and always heartbreaking. In 2017, decades after the research trips that had taken him to asbestos mines in South Africa, Jock McCulloch, one of the authors of Defending the Indefensible, was diagnosed with mesothelioma, and died less than a year later. His message to fellow asbestos campaigners before he died was simply to keep working. “It is an important and ongoing struggle,” he said. “Because some gains have been made, that does not mean those gains will endure.”

Historian Jessica van Horssen was unable to trace the descendants of the dead miners whose lungs were stolen, and for whom she had hoped to salvage some dignity. Instead, she tries to do justice to their memory by standing up for the dignity of the working classes and advancing our understanding of toxic substances. Nancy Tait’s contribution was acknowledged with an MBE in 1996 and an honorary doctorate in 1999. She fought for asbestos victims until her death in 2009.

A year after Dad’s death, Mum finally collected his ashes. As I held them heavily in my arms, I thought about all the good times: the camping, the walks in the fresh air and the laughter. But I can’t help but wonder if there are tiny fibres of asbestos mixed with the ashes. Asbestos is, after all, indestructible.

Correction: The article originally stated that official data does not record the deaths from mesothelioma of people older than 74. In fact, official data does not record the occupations of people older than 74 whose deaths were caused by mesothelioma.