Over the past decade, the United States has been devastated by fentanyl—a synthetic opioid said to be 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine. The synthetic opioid crisis, in which fentanyl is central, has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and, at one time, killed one person in America every five minutes.

It might seem like a purely American problem, but policymakers have warned that synthetic opioids may be coming to Europe. Speaking at the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs in March, US secretary of state Antony Blinken said the US had been a “canary in the coal mine” when it came to fentanyl. “It hit us hard, it hit us first, but unfortunately not last,” he said. “And we can see its ravages taking hold in other countries.”

Josh Torrance, a drug researcher at the University of Bristol, also sees trouble ahead. “I’m sitting here in my office and I’m scared about the UK opioid supply,” he says. The UK has a serious and growing problem with drug-related deaths. In 2022, drugs contributed to the deaths of 5,000 people in England and Wales—the highest figure since records began in 1993—and just under half of those were confirmed to have involved an opiate.

What’s more, Scotland has the highest drug death rate in Europe. Some 80 per cent of the 1,051 drug-related deaths in 2022 (the latest year for which figures are available) involved an opiate. In the first nine months of 2023, there were at least 25 deaths related to the class of synthetic opioids called nitazenes, which are often found in street heroin and black market sedatives.

In the summer of 2023, seven people who died after taking drugs in the West Midlands—two living in a homeless hostel and five in houses of multiple occupancy—were found to have consumed nitazenes. In December 2020, a teenage boy from Cheshire took a pill he had bought on the dark web and died of an overdose. He thought he had purchased oxycodone—a highly addictive, prescription-only semi-synthetic opioid that is used to treat pain—but the pill contained nitazenes. Overall, more than 100 recent drug-related deaths in the UK have been officially linked to nitazenes—and it’s a figure that is set to rise further.

Nitazenes, rather than fentanyl, appear to be Europe’s opioid of choice. They are thought to be at least as strong as fentanyl, but some are much stronger—and the margin of error between a dose that will get you high and one that will kill you is much slimmer. This is the root of Torrance’s fear: if someone unknowingly buys a bag of heroin that has been mixed with nitazenes, the chance of overdose increases massively. In April, a BBC investigation found that nitazenes had been advertised on social media platforms, despite them being illegal.

Nitazenes are thought to be at least as strong as fentanyl, but some are much stronger

Experts attribute the appearance of nitazenes in the UK to the Taliban’s crackdown on poppy farming in Afghanistan, which supplied about 95 per cent of Europe’s heroin. The sophistication of Europe’s heroin-trafficking networks, as well as excess stores of opium in Afghanistan and along trafficking routes, means that the UK has not yet experienced a total heroin drought. But the latest figures for drug seizures in England and Wales suggest that supplies are falling.

In the year ending March 2023, UK police and Border Force seized 33 per cent less heroin than in the year before, despite Border Force making the highest number of drug seizures on record. Later last year, British law enforcement made its largest ever haul of synthetic opioids, seizing around 150,000 tablets containing nitazenes from a factory in east London set up to manufacture the drugs.

The risk is that if the people who sell drugs are worried about dwindling stocks or rising costs, they may begin to adulterate their product with cheaper, stronger substances, such as nitazenes. For now, this has only been happening on a localised level, with post-mortem toxicology results identifying clusters of nitazene-related deaths in Birmingham, Scotland, Norfolk and Northern Ireland. The majority of the heroin flowing through the UK is, indeed, still heroin. But if opium farming in Afghanistan is not resumed—and there are no signs it will be soon—the influx of synthetics into the UK’s opioid supply will be less of a trickle and more of a torrent.

Yet synthetic opioids will not have the same consequences in the UK as they did in the US. America’s opioid crisis is the result of a very specific set of circumstances. Harry Shapiro, director of information service DrugWise and a researcher with over 35 years in the field, says that the difference in the two countries’ healthcare systems means it’s “almost impossible for it to be replicated in the UK”.

Shapiro explains that, in the US, the over-prescription of opioids to treat pain—real or not—from both well-meaning physicians and “rogue doctors” operating out of “pill mills” has led to a surge in opioid dependence and addiction. When people could no longer afford to pay hundreds of dollars for their prescriptions, they turned to the black market, purchasing street heroin and fake pain pills supplied by the Mexican drug cartels. In order to keep up with demand, cartels began to import fentanyl and its precursors from China. They then mixed fentanyl with heroin and pills in order to make their supplies last longer. Researchers at the University of California believe that the US opioid crisis is now in its “fourth wave”, with fentanyl permeating the US drug supply, showing up in cocaine and other stimulants and affecting those who were not previously addicted to opioids.

Currently, it is not thought that nitazenes will begin to adulterate other types of substances in the UK, such as MDMA and ketamine. Even though opioid prescriptions are rising in the UK, the more than 300,000 people who use opioids problematically are much less likely to be on pain medication (through prescription or the black market) and are more likely to be long-term injecting heroin users. Even if the heroin supply were to become more contaminated by synthetic opioids—a situation that experts say is likely but not guaranteed—a much smaller subset of the UK population would be impacted than is by the opioid crisis in the US.

In the UK, the people most at risk are injecting heroin—particularly those who are homeless and experience multiple disadvantage or chronic poor health—or are “opioid-naive” (those with no tolerance to opioids) and using black market sedatives called benzodiazepines, either dependently or recreationally. But, as experts rightly note, the issue does not need to reach anywhere near the extent of the US crisis to be a cause for concern—and the sooner that policymakers are able to act, the better.

If synthetic opioids do arrive in larger numbers, it will probably take authorities a while to notice. The majority of data comes from drug seizures and coroner reports. But, says expert Caroline Copeland, “Not every death is investigated by a coroner, not every death that is investigated by a coroner has full post-mortem toxicology—and not every toxicology [report] is fully comprehensive for every compound under the sun.” Copeland runs the National Programme on Substance Use Mortality, which collects data reported voluntarily by around 90 per cent of coroner’s offices around England, Wales and Northern Ireland. “While this gives us an idea of the general trend, it’s difficult to get 100 per cent numbers,” she adds. Not to mention most results are only reported at the conclusion of an inquest. Across the country, it takes an average of seven months for an inquest to be concluded and it can take as long as two years. Given the delay, it’s impossible to know just how far-reaching the problem may already be.

However, there could be other ways, beyond data on drug busts and fatal overdoses, to fill in the picture.

Between July and October 2023, Mark Pucci, a consultant in clinical toxicology working in Birmingham and Sandwell, collected data from people presenting with non-fatal overdoses and other drug-related issues at local hospitals. At least 19 patients were shown to have consumed nitazenes, indicating they are more prevalent in the drug supply than overdose figures alone suggest. However, there is no centralised system in the UK to monitor non-fatal overdoses at present.

Health experts have criticised the government for acting too slowly

The government is now developing an early warning system that will include “state-of-the-art monitoring for the presence of synthetic drugs by analysing wastewater, or recording spikes in overdoses in specific locations”. But health experts have criticised the government for acting too slowly, particularly in regards to non-fatal overdoses. “Tracking non-fatal overdoses requires focus, dedication and money,” says Judith Yates, a retired GP who also collates data on drug deaths in Birmingham. “We’re very lucky in Birmingham to have two very good toxicology labs, and the toxicologists themselves are very open to it, but they don’t have the funding.”

Yates, who also collates data from the Welsh government-funded online drug testing service Wedinos (the Welsh Emerging Drugs and Identification of Novel Substances), believes that real-time data about what is actually in the drug supply is vital to halting a synthetic opioid crisis. Her analysis of Wedinos data found 145 instances of nitazenes since 2021, 73 of which appeared in 2023, and a further 44 between January and April this year.

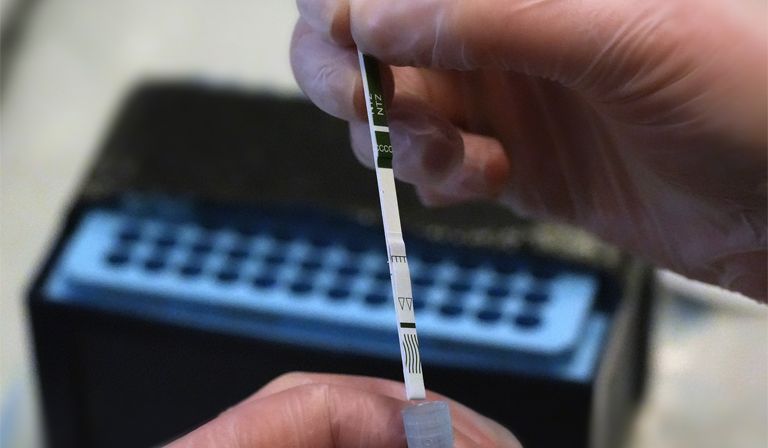

Earlier this year, the UK’s first ever regular, in-person drug checking service opened in Bristol city centre, run by harm-reduction charity The Loop. Here, people who use drugs dependently are able to legally have their drugs tested, with results given back during a non-judgemental consultation within an hour of submitting them. Data is also shared with health agencies and law enforcement to help gather more robust information about the drug supply in the local area. People who use drugs are then able to make an informed decision about whether or not they will consume what they have bought. They can also get access to naloxone, a life-saving drug that reverses opioid overdoses, as well as other harm-reduction services.

While Wedinos and The Loop’s service are invaluable, they require people who use drugs not only to know about them, but to be willing to give up some of their drugs. And many more such services are needed up and down the country to have a national impact.

Beyond improving data collection, the government has taken the much-welcomed step to widen access to naloxone. It also recently made the decision to label 14 nitazenes as class A drugs under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, as part of its commitment to “tackling the supply of illicit drugs through relentless policing action”.

In theory, says Shapiro, the class A label will allow law enforcement to focus its attention on these drugs. However, as is often the case with synthetic substances, the government could end up in a game of “whack-a-mole”, because chemical compounds can be tweaked ever so slightly to evade the law. We witnessed this with mephedrone and synthetic cannabinoids in the 2010s. “It’s a political process that you have to go through,” Shapiro says. “Whether it makes a difference to the supply and use of these drugs is doubtful.”

Since the Misuse of Drugs Act was introduced half a century ago, successive governments have tended to respond to any issue regarding drugs with criminalisation, but evidence suggests that it does little to protect those actually at risk of drug-related harms—namely the people who use them. Drug busts drive up overdoses in surrounding areas, and can increase drug-related crime and violence. André Gomes, who works with Release, an organisation that specialises in analysing UK drug policy, says that drug policy is being “held hostage” by this criminal perspective, and that taking a public health approach to the issue is the best way to reduce harm. “We are already topping the league as one of the deadliest countries in Europe for people who use drugs and we’re starting to see more and more signs that there are other dangerous adulterants entering the drug market,” he says. “This looks, smells and walks like a public health emergency… Health funds need to be unlocked, and that means directing money away from the criminal system and towards treatment services and health interventions, and not criminalising people who use drugs and are looking for help.”

Not only do funds need to be unlocked, they also need to be directed to those who need them most. As Max Daly, former global drugs editor at Vice and co-author of Narcomania: How Britain Got Hooked on Drugs explains, myths—for example that fentanyl is being found in cannabis and ecstasy, or that police officers are collapsing simply by coming into contact with fentanyl—can be dangerous. “All this does is divert already scant resources to everyone, when, in reality, there are particular groups of people who are way more at risk of overdose, and you need to direct most of your harm reduction and resources towards helping them,” says Daly.

But unlike the Covid-19 pandemic, this health crisis is not a completely novel problem. There is evidence of what does and doesn’t work to save lives during an opioid or overdose epidemic. “We have the global tools to know what to do,” Gomes continues. “We’re just being incredibly stubborn about it.”

More radical approaches to drug policy may help, such as the introduction of harm -reduction-based policies alongside a fully funded, fit-for-purpose drug treatment sector. The main concern with nitazenes is that people will overdose, not that they have an addiction, which suggests policies should be geared less towards recovery and more towards saving lives.

The UK’s drug treatment services are malnourished as a result of both budget cuts and approaches that are focused on recovery, and so deprioritise things such as heroin-assisted therapy (HAT), an evidence-based solution that works especially well for those who use drugs chaotically. “Britain used to have the gold standard of drug treatment—it was known as the British Model—and that was when doctors were able to prescribe and administer medical-grade heroin, also known as diamorphine, to people who needed it,” explains Chris Rintoul, head of harm reduction at charity Cranstoun. A pilot for HAT, which ran in Middlesbrough from 2019 to 2022, was found to significantly reduce not just crime, but service users’ reliance on potentially adulterated street heroin; it was later closed due to a lack of funding. Not everybody needs HAT, but giving certain people what they actually need in order to keep them engaged with treatment works in many cases.

The Misuse of Drugs Act made prescribing heroin much more difficult, and marked the end of the “golden era” for harm reduction. Now, most people in treatment are offered opioid substitution treatment—usually a daily dose of methadone or a monthly injection of buprenorphine. Both of these treatments work really well, when applied effectively. But many services are not able to offer same-day prescriptions, which require a rapid drug test, because they get held up by bureaucracy and a lack of funding. When engaging people with drug treatment, it’s important to strike while the iron is hot; 24 hours can make a huge difference.

Another issue, Rintoul notes, is the lack of understanding about drug use from drug and alcohol treatment service workers themselves, who may not realise that many people who inject drugs, especially those at the sharp end of this crisis, do so at least partly because they have had extremely traumatic lives. PTSD and opioid-use disorder are known to be comorbid, and those with PTSD are more likely to overdose and engage in criminal activity. “If you speak to people who use drugs about recovery, motivations for change, prescriptions, etcetera, they aren’t going to want anything to do with it,” he says.

If preventing overdose is the goal, says Shapiro, there are also few better solutions than overdose prevention centres (OPCs); facilities where people who inject drugs are able to do so under the supervision of medical professionals, with clean equipment and life--saving naloxone on hand. There are around 200 OPCs globally and, so far, there have been no recorded deaths in any of them. “Under the circumstances, I think it does behove the government to do all it reasonably can to save lives,” says Shapiro. “We have policing and border control, but accepting the fact that a heck of a lot of stuff gets through despite all of that, I think the government has a moral obligation to allow these kinds of facilities to open up—properly managed, where they’re needed, for a targeted group of people who inject drugs.”

The UK’s first OPC is opening in Glasgow this summer, after an unsanctioned OPC operated by harm reduction worker Peter Mcleod (née Krykant) was able to prevent nine overdoses in nine months. This has only been possible because Westminster decided to turn a blind eye to Holyrood’s decision to allow them, rather than backing OPCs as policy. Critics worry that such policies encourage drug use (although Shapiro says this is “nonsense”). In fact, OPCs have been found to decrease drug litter in public spaces and are instrumental in facilitating drug treatment, including opioid substitution, and, in some cases, helping people to stop injecting altogether.

None of these treatments or services are a magic bullet, Rintoul notes. When drug treatment policies are viewed as one-size-fits-all, there are always unintended consequences for some people. The most important thing in addressing this problem is to have what Torrance calls a “wraparound service”, whereby people who use services like drug checking and OPCs are also able to access different types of treatment options—in addition to naloxone.

With more and more people dying from drug-related harms every single year, it’s clear that the government is not winning the war on drugs. With this new, even more dangerous battle against synthetic opioids on the horizon, a change of strategy is not just advisable, but essential.