Fewer candidates are standing in this election than at any election since 1992—a development which could have important consequences for the overall result. After all, the splintering of the rightwing vote towards the referendum party and the early incarnation of Ukip had a bearing on the scale of John Major’s landslide defeat in 1997 and minor parties, though they win few seats themselves, have often had a bearing in close contests between the main players ever since.

So why are there fewer candidates this time? It is due not just to a smaller number of independent or minor party candidates, but also to a smaller number of candidates from UKIP and the Greens. Between them, these two parties are putting up 345 fewer candidates than they did in the last general election.

There are heroic and prudential explanations of both parties’ decisions to compete in some constituencies and not others. On the heroic interpretation, the Greens and UKIP have stood down in order to further a more important cause: a progressive alliance capable of stopping the Conservatives in the case of the Green party, and a pro-Brexit alliance in the case of UKIP.

On the prudential explanation, both parties have decided not to stand candidates in areas in which they would likely have done very poorly, and lost their deposit.

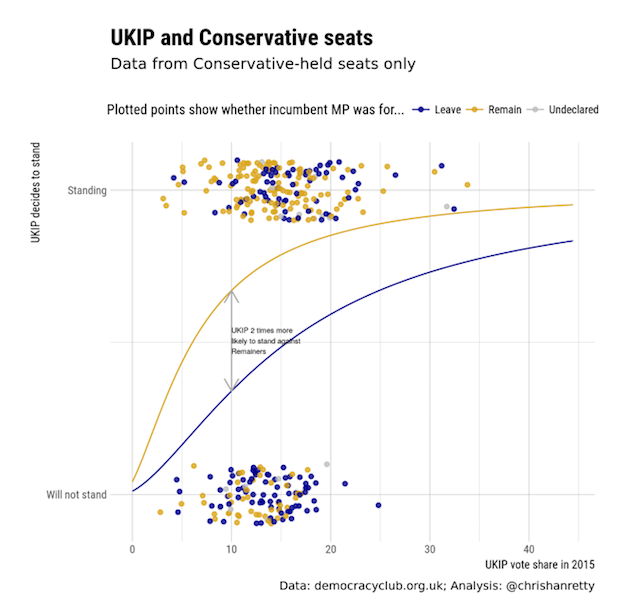

Which of these explanations comes closer to the truth? Let’s concentrate on the case of Ukip, which has garnered many more votes and swung many more seats than the Greens in recent times. It turns out, that this party responded equally to both our factors. Figure 1 shows Ukip’s previous strength in each constituency (on the horizontal axis), and whether or not the party is standing a candidate (on the vertical axis). Separate trend lines are plotted depending on whether the incumbent MP supported Remain in the referendum campaign.

Although UKIP is much more likely to stand in areas where it was stronger in 2015, the effect of having a Remainer incumbent is significant. Consider the case of a seat where it polled a fairly typical 10 per cent last time (nationwide, Ukip got 12.6 per cent in 2015), the party is now twice as likely to stand against a Remainer as it is to stand against a Leaver.

This isn’t an artefact of Labour MPs being more likely to support Remain. The same pattern holds when we focus just on Conservative MPs, as shown in Figure 2.

UKIP’s past performance matters slightly more in explaining candidacy decisions, but it’s a close-run thing. The figures plot general trends, and obviously there will be exceptions where UKIP has stood candidates against vociferous Leavers and vice versa. But it does indicate that, at least on the candidate “supply side,” this could be a Brexit-tinged election. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the contest will push us towards a more hardline Brexit parliament.

For a start, Ukip’s determination to take on Remainer MPs, could actually be good news for Labour. Sure, because more Labour MPs are Remainers, more will face a Ukip challenge, but the effect is going to be to split the right-wing Eurosceptic vote. If UKIP votes would otherwise go to the Conservatives, then the continuing presence of Ukip candidates in Labour seats reduces the chances of the Conservatives winning more seats in the north and midlands. The thirteen seat Tory bonus, which my initial rough analysis of the candidate numbers suggested, may be cut to just five or six in the light of this more refined information about where Ukip is stepping aside.

The consequences for the balance of “harder” or “softer” Brexit forces within the Conservative Party are unclear. If the Conservatives do win a large number of seats from Labour, then many of the new Tories will have won without any Ukip help in the form of candidates stepping aside. If many Conservative PPCs are happy to “go along to get along” on Brexit for reasons of their career, then the new parliamentary cohort may feel as though they owe nothing to Ukip, and everything to the prime minister. As the details firm up that could encourage more flexibility than the hardliners would want to see.

So in both senses then—party balance in the Commons, and the Brexit balance within the Tories—it is at least possible that Ukip’s “heroism” could actually work against the hardline that the party would want to see.