What does it mean to be a Conservative? For Lord Salisbury, it was about standing firm against the “army of so-called reform.” For Disraeli, in some moods at least, it was about healing the rift between England’s two nations. And for Tony Hancock, it was an acceptable patriotic alternative to giving blood.

The lack of any agreed answer hasn’t stopped the tribe that bears the Conservative name from being, in England at least, the natural party of government; it has been a source of great adaptability and advantage. But today, as Andrew Gamble sets out, the whole European centre-right is under new pressure from resurgent nationalist populism to define itself much more sharply. And in the UK, with the clock ticking down towards Brexit, these dilemmas are particularly urgent. The Tories stand on the cusp of making decisions that will not only be fateful for the country’s place in the world, but will also define what—and who—the Conservatives stand for today.

With her “backstops,” “implementation phases” and panicked last-minute compromises, Theresa May has kicked cans down the road wherever possible precisely because she senses that any decision that gives the Tories more definition will be dangerously divisive. And she may well be right to fear the unforgivingly bright light that Brexit is casting on the party’s ideas and priorities. For the doctrinal haze that sits at the heart of Conservatism has served it well.

The long list of values that have, at one time or another, been associated with Conservative thought—including freedom, authority, community, individualism, tub-thumping militarism and world-weary pragmatism—is varied to the point of self-contradiction in theory. No wonder that its intellectuals have pleaded that Conservatism is not “a doctrine, but a disposition” (Michael Oakeshott) or “not so much a philosophy, as an attitude” (Quintin Hogg).

As for the practice, the application of all this is positively dizzying. Traditional community? It counted for little when Thatcher was consigning old industries and ways of life to the scrapheap. Militarism? The party lurched from Edwardian jingo to interwar appeasement—before it supplied Britain’s greatest belligerent in 1940. Liberty? The party suspended habeas corpus in the 19th century, but then supplied the lawyers who drafted the European Convention on Human Rights in the 20th—only to regret this achievement by the 21st.

If politics was confined to debating societies, all this sliding about would spell a Conservative rout. Liberals, socialists and assorted other rationalists have often imagined that their day is coming because they judge that they’re winning the ideological argument. Yet more often than not, the Conservatives have cleaned up, precisely because of their willingness to jettison inconvenient ideological baggage.

Some may see Brexit as a profoundly un-Conservative thing to do—it tears up relationships and institutions rooted in 40 years of experience, and sacrifices established advantages for an unknowable future. When it comes to the fate of the party as opposed to the nation, however, this doesn’t necessarily matter.

Indeed, the Conservatives are today, if anything, narrowly ahead in the polls. If there is any centre-right party in Europe that you would expect, on the strength of its record, to find a way through the challenges of resurgent nationalism and Brexit, then it would be the Tories.

But whereas the Conservatives have often regrouped and survived crises that should have torn them asunder, on rare occasions, a schism has proved more fundamental, and a party that exists to wield power has ended up out of office for a very long time. As May looks ahead to more crunch votes and possible painful concessions on Brexit, the question I’ve been putting to the most thoughtful Tory politicians I know is whether or not Britain’s departure from the European Union will provoke nothing more than another in the long line of Conservative reinventions, or whether it could prove to be one of those rare crises that really does sink the Conservatives.

History lessons

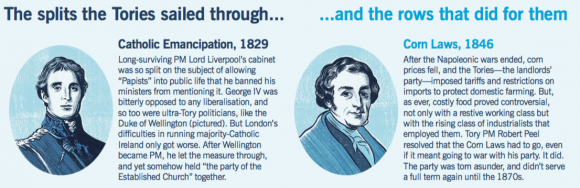

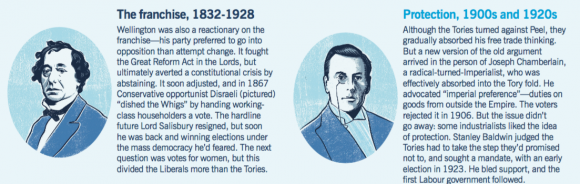

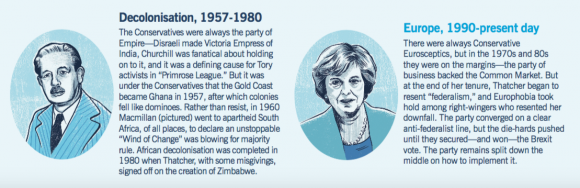

The past is always alive in a party of tradition: the ninth Duke of Wellington, an active Remainer in the Lords, has invoked the first Duke’s tricky judgment calls in discussing how much the upper house can reasonably hope to hold out for as it seeks to soften Brexit. And, amid the argument about a “meaningful vote” on the deal with Europe, in which parliament is trying to claw back a measure of control from the executive, another Tory peer with even more venerable lineage said his ancestor had tried something similar while working with Cromwell, and ended up losing his head. So what can we deduce from the history books about when the Conservatives have—or more rarely have not—been able to come through a crisis intact? The Conservatives have virtually always been able, in the end, to deal with disputes about abstract values, even seemingly-foundational ones. In the 19th century the Tories were, before anything else, the party of the Established Church. Wellington saw it as integral to the fabric of the nation, and was fiercely opposed to Catholic Emancipation. But when he realised there was no practicable alternative means to safeguard the Union with Ireland, the Iron Duke bent and let it through. Where is the parallel today? Think of the right-wing talk about diversity threatening the British way of life. That was probably always more of a Ukip narrative than a Conservative one, but it was certainly there on the party’s fringe. Now that immigration is declining, however, none of the Tories I spoke to believe that it poses an existential threat. There will be wrangling over free movement, then compromises—and then something else to do. Another core Conservative value used to be aristocracy, which is why Wellington’s Tories refused to countenance reforming the franchise in the early 1830s, preferring to go into opposition, where they continued to dig in against the Great Reform Bill for as long as they dared. But in the end, after much parliamentary attrition and an election defeat, they folded by abstaining in the Lords. Something similar happened 80 years later when, after fiercely resisting the People’s Budget, the Conservative-dominated Lords eventually acquiesced in its own weakening through the Parliament Act. The Tory Party, then, has often been cantankerous, but—as Geoffrey Wheatcroft wrote in these pages in June 2017—its redeeming virtue has always been “knowing when to stop.” So maybe, in the Brexit context, it will revert to that traditional wisdom. In other moods and circumstances, the Conservatives have been ready to embrace practical change—as when Disraeli extended the vote to working-class householders in the boroughs in 1867. Once again, in theory, this should have spelt ruin. The Conservative frontbench lost its more dogged (or principled) reactionaries, such as the future Lord Salisbury who resigned. But having no chance of reversing the tide for democracy, and with nowhere else to go, he soon came back on board. All this ancient history might suggest that ending up with—say—a soft Brexit will produce nothing more than a passing sulk from high-falutin’ Europhobes like Jacob Rees-Mogg. But might Brexit be different because it is about the “direction of the nation”? Surely there can be no compromise over that for a patriotic party? History suggests exactly the opposite: think of decolonisation. It was so painful for establishment forces in France that it produced not the fall of a mere political party, but the collapse of a constitutional order, the Fourth Republic. In Britain, by contrast, the same Conservative Party that had crowned Victoria as Empress of India proved up to leading the process, with Harold Macmillan’s Wind of Change. Another even more fateful schism came in the 1930s: appeasement versus rearmament. The nation’s fate turned on the outcome, but the party proved perfectly able to adjust from the complacency of Baldwin and Chamberlain to the bombast of Churchill without falling to pieces. Indeed, some supporters of Munich, such as Rab Butler, went on to play starring post-war roles.Losing interests

At this point, Brexiteers might be concluding that the Conservatives can go for as hard an exit as they like, and count on the Europhiles such as Ken Clarke and Anna Soubry to suck up the new realities. But adaptable as they are, it is wrong to presume that the Tories can make up after any row. Rare disputes really have torn them apart. These have tended to be rows in which the real issue is not abstractions—about ideas, or even the nation—but raw questions of interest. The archetypal case is the Corn Laws, which the Tories had originally imposed to protect landowners from imported grain. Robert Peel scrapped them because he could see that social and economic progress would not be served by artificially costly food. Two-thirds of his largely-landowning MPs disagreed, and voted against him: he prevailed only with opposition support. It took a generation for the party to piece itself together again.

The Tory story on Europe

So where does Brexit sit in the light of this backstory of rows, regular regroups and occasional serious splits? Europe is not, of course, a new dividing line. It is easy to forget now, but for much of the time, it was handled without serious difficulty. Eden was fiercely against “going in,” but his successor Macmillan was staunchly pro. The divisions were still there when Heath took Britain in and Thatcher pushed the single market. But in the 1970s and 80s, the “anti-marketeers” were oddballs like Enoch Powell and Teddy Taylor, an unusual blend of an animal rights supporter and a hanging obsessive. Things got more serious after the lady herself turned in her Bruges speech, and pro-Europeanism became linked in many eyes—including her own—with the “betrayal” that ousted her. Rank and file suspicions of a European “plot” for integration were stoked by Norman Tebbit on the conference platform and Thatcher herself off-stage right. Then, under John Major the previously-obscure Eurosceptics Bill Cash, Teresa Gorman and Iain Duncan Smith achieved prominence, along with Tony Marlow in his boating club blazer. The PM was caught describing Eurosceptic cabinet colleagues as “bastards,” and by 1997, two dedicated upstarts were snapping at the party’s heels: Ukip and James Goldsmith’s Referendum Party. The infighting reached such a fever pitch that Major was forced to revise and re-record an election broadcast about Europe. That year saw the divided Conservatives endure a rout, but it wasn’t clear that the European issue would, in itself, consign the Tories to the margin for long. Under first William Hague, and then Duncan Smith and Michael Howard, they converged on a newly-sceptical line. The rhetoric—“In Europe, but not run by Europe”—reeked of compromise, yet that is often the essence of politics, and in rejecting the euro, the Conservatives were in tune with the country. They began recovering in votes in 2001 and seats in 2005, and when the young David Cameron took up the reins and told his party to stop banging on about Europe, there was no great backlash. To the casual observer, it may have looked like one more Conservative rift had healed. But the truth is that Cameron, a casual Eurosceptic, never felt able to ignore the zealots. Even in opposition he pulled the Tories out of the European People’s Party, and in government he wielded a posturing veto concerning the eurozone crisis that put Britain outside the room. And within months of Ukip’s mid-term surge in the polls he had conceded the referendum that would destroy him.A schism made on Fleet Street

Why? Sure, immigration was popularly perceived as a problem, but Europe itself virtually never registered among the top issues for the voters. Cameron felt little need to pander to the hard right on gay rights, race relations or crime. In unravelling this mystery, we also get to the divide that the Conservatives—going right up to cabinet level, who cheerfully spoke to me off the record—all agreed was now the most fateful for their party’s future. It is not the divide between Leavers and Remainers, but rather the divisions between Leavers of different sorts. The undoubted preoccupation with Europhobia in Cameron’s mind, and its continuing clout in the Conservative Party, originally arose because of the attitude of papers like the Sun and the Telegraph, and it reflects the worldview of offshore owners Rupert Murdoch and the Barclay brothers. These border-straddling businessmen had no wish to see Britain retreat behind trade barriers. Rather they envisaged an island economy that would cut free of the continent, slash tax and red tape and then be—in the words of the Barclay-owned Spectator’s pre-referendum cover—“Out, and into the world.” Many “Leave” voters out in the country would like to get back to the days, imagined or otherwise, where “Brits buying British” resulted in good manufacturing jobs. In a NatCen Social Research poll, half of them thought Britain should limit imports to protect the UK economy; other polls have found that Leavers are far less interested in cutting global trade deals than curbing immigration and reclaiming sovereignty. The odd Tory backbencher reflects this a bit: in June, Edward Leigh told the Commons how he admired Donald Trump’s willingness to tackle the Chinese for dumping cheap goods on world markets. But there is little overt protectionism within today’s parliamentary party. The three most prominent Brexiteers in the cabinet, Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and David Davis, all have at least some libertarian tendencies, the first two being journalists who have some of the same aversion to regulation as the press barons. Far from being a sincere “pull up the drawbridge” man, Johnson once advocated bringing Turkey into the EU. All of them talk—as do hardliners outside the government, such as John Redwood and Rees-Mogg—as if Brexit’s end result will be Britain trading more freely.

***

For if and when Britain leaves the single market, the “passporting” rights of the City—a bastion of financial support for the party—to trade throughout the continent will go. Remainers inside government tell me that they do see the potential for managing the consequences, but only if sensible and cordial relations with Europe are contained. As Nicolas Véron wrote in these pages at the end of last year, where losses of perhaps a tenth of the City’s activity are probably already baked in to Brexit, a quarter could easily be vulnerable if we get the detail wrong. In that event, a hole in the public finances would compound the misery of a government already confronting anxiety out in the country. At the same time, a lonelier Britain, and its currency, could become newly vulnerable in financial markets which have indulged its current account deficits—a doubling down of the effect that we saw in 2016, when sterling sank after the “Leave” vote. Savers wouldn’t like that. As for industry, it is already starting to ask searching questions about who it trusts to run things in its interest. In June the President of the CBI, Paul Drechsler, was blunt: while the government was “playing politics,” he said, “in the world of business, we’re frustrated. We’re angry.” A chaotic Brexit could set the interests of nostalgic “Leave” voters in the country against those of the free-trading libertarian visionaries who have, somewhat peculiarly, become their champions in Westminster. It would run risks with the “sound money” savers who have always been the backbone of Conservative support, and at the same time alienate some of the financiers and entrepreneurs who have traditionally provided the financial backing. That sounds like the kind of cocktail of circumstances which might poison a political party—even one that’s been bouncing back from all sorts of scrapes for 300 years.