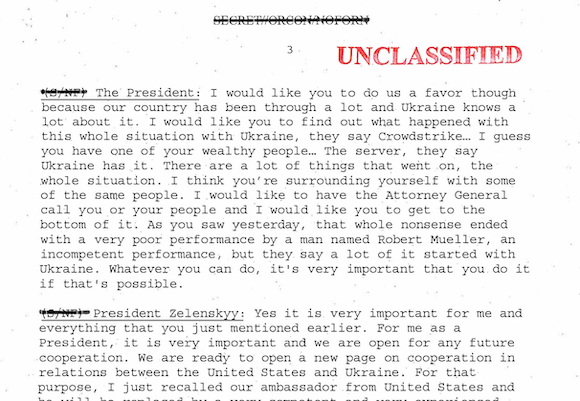

A transcript of the call in which President Trump asks Ukrainian President Zelensky for “a favour” It was a smug move by a confident reformer. On 23rd September Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky signed a bill enabling the impeachment of the head of state, hitherto impossible under Ukrainian law, as part of his reform package. The following day US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced impeachment proceedings against President Trump. Zelensky and Trump were suddenly mirror images of governance—one good, one ill.

The revelations about Zelensky’s telephone call with Trump may yet be the US president’s undoing. As the transcript reveals, Trump pushed Zelensky to initiate investigations into the son of a putative electoral rival. The subtext was that failure to comply would result in the withholding of US$390m of vital military aid.

Zelensky didn’t come out of the call well either. The transcript showed him cringingly eager to please. “I had an opportunity to learn from you,” gushed the Ukrainian to Trump, “we used quite a few of your skills and knowledge.” But so far Zelensky—a man as unlikely a president as Trump himself—has not been badly damaged.

This time last year Zelensky was the lead actor in Servant of the People, a political comedy, playing Vasyl Holoborodko, a humble teacher who is so sickened by his country’s corruption that he makes an impromptu rant to a colleague in an empty classroom, but is filmed on the sly by a pupil—the resulting clip gets a rapturous reception on the internet. He runs for office and is catapulted to the presidency by a landslide.

Servant of the People became one of Ukraine’s most-watched television series—it also sparked a political flame inside Zelensky himself. He engineered a lightning three-month campaign waged almost entirely on social media, and captured the presidency in April with 73 per cent of the vote—more even than Holoborodko.

It is hard to know whether fact or fiction was more improbable, but the face of the incumbent Petro Poroshenko during the televised presidential debate said it all: shock and disbelief that a TV funnyman from an entertainment show hoped to lead a country at war. But the majority of Ukrainians, some of the world’s least optimistic voters, felt that Zelensky was a gamble for change worth making.

Zelensky was everything that his competitors were not—easygoing, funny, fresh. For 15 years this bumptious comic, and leading man in numerous romantic comedies, was as popular in Russia as in Ukraine. Commanding high fees for his stage and screen appearances, he was probably a millionaire by 30. To boot, he was a capable businessman who has run his own production company for over a dozen years.

Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg with Zelensky in OctoberZelensky’s campaign was astonishingly lean. There were no foreign spin doctors, smear campaigns, attempts to buy votes or meddle with the electoral system, all notable features of previous Ukrainian electoral campaigns. Zelensky’s secret was the internet. He worked with a small team operating in secrecy, bombarding YouTube and Facebook with daily content. Appearing in casual dress, often in jeans and a hoodie, with a selfie stick, Zelensky spoke directly to the people in his deep breathy voice, too husky for such a youthful elfin face, combining sharp insights, folksy musings and messages of often staggering banality.

Most importantly, Zelensky was not a politician. He was an outsider committed to rooting out entrenched interests, namechecking those Trumpian tags to “drain the swamp,” “destroy the deep state.”

But there, the parallels with Trump run out. Zelensky is no populist. He is an EU- and Nato-supporting centrist who speaks continually of unity not division. He does not curry favour with one Ukrainian constituency over another, as his opponent Poroshenko did. There is no hard-done-by majoritarian base Zelensky seeks to please, and the corruption he rails against is all too real. His instinct is to unite, not to tub thump, and he has made a serious bid to break the deadlock in Ukraine’s war with Russian-backed rebels. Whether he succeeds is another question. But in a few short months Zelensky has already removed lawmakers’ immunity from prosecution, a long-cherished refuge for oligarchs entering politics for the wrong reasons.

As much as the phone transcript paints him to be out of his depth, Zelensky is on an important course. While Trump appears interested in re-election by any possible means, Zelensky’s ambition is to turn Ukraine into a normal European country.

The bigger question is whether he can make good on his anti-corruption promises, which keep the west, especially the IMF, sympathetic to Ukraine’s cause. But with Russia poised to return to the negotiating table, a distracted Washington is bad news. Whoever wins the White House next year, Zelensky needs all the US clout he can get in the diplomatic minefield ahead of him.