For a lawyer, this is a curate’s egg of a book—parts appear excellent, but those are the parts that I am least qualified to judge, because the author is a Christian and a professional ethicist and I am only one of those.

The title—What’s Wrong with Rights?—is not excellent. As the author accepted in an illuminating webinar organised by the think tank Policy Exchange, there is much that is right about rights, insofar as they fit within his paradigm: a legal right, possessed by an individual or corporation and designed to secure an important element of human or commercial flourishing backed up by authority. Nigel Biggar, who teaches theology at Oxford, wrote this book because, in his view, there are four things wrong with the way some people talk about rights. (These will chime well in those political circles where there is currently agitation to pare back human rights protection.)

First, some people say that human need generates a moral right to have that need met, but there cannot be such a right without identifying a body with the corresponding duty to meet it (a point long made by philosopher Onora O’Neill, referring to “welfare rights”). Second, such people do not understand that legal rights have to depend on the prevailing circumstances: if there are no lawyers to defend people accused of heinous crimes, as in Rwanda after the 1994 genocide, it is better to have a less-than-perfect system of trials than none at all. Third, some rights are expressed at a high level of abstraction, which gives too much power to courts to decide on controversial issues that ought to be decided by democratically accountable legislatures. Fourth, the dominance of “rights-talk” neglects the wider moral dimension to our conduct: just because we have the right to do something does not mean that we ought to do it.

Biggar’s principal target is a certain kind of “rights-talk,” which stems from what he calls “rights-fundamentalism.” But it takes him a long time to get there. The first five chapters are devoted to a detailed and scholarly discussion of the views of selected authors on whether or not there are natural rights—rights which are not legal but which stem from the nature of human existence.

He begins with the “sceptical tradition,” epitomised by Edmund Burke, Jeremy Bentham (for whom natural rights were “nonsense upon stilts”), David Ritchie and Onora O’Neill. From them he distills a set of objections to natural rights. He then proceeds to test these: first, against the concept of natural rights as it was developed in the late medieval and early modern periods; second, against the claims to natural, even God-given, rights in the American and French Declarations of 1776 and 1789, and later in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights of 1966; and third, against the modern Roman Catholic tradition, with a focus on the work of Oxford’s John Finnis.

From this discussion he identifies a list of problems with the concept of natural rights: attributing to them the same security and stability as positive (legal) rights; asserting rights to “liberties or benefits whose lack of definition permits ludicrous or recklessly licentious construals”; getting carried away with its own high-flying rhetoric; confusing a specific historical form with the right itself; asserting rights to benefits without assigning a duty to supply them to a particular body; failing to talk about the duties of the rights-holder; and displaying the “conclusionary force,” which asserts at the beginning what needs to be argued and proven. Drawing all this together, he writes that there is “a set of moral principles that are given in and with the nature of reality, specifically the nature of human flourishing. There are also positively legal rights that are, or would be, justified by natural morality. But there are no natural rights.” He agrees that “modern liberal society cannot live on rights alone.” We need more than that. But that does not mean that his paradigm of legal rights is invalid.

I am not qualified to judge the scholarly accuracy of this discussion. I dislike the style of philosophical argumentation which goes “X says this and X is wrong for the following reasons,” often assuming that the reader knows what X is talking about, rather than an account of the author’s own thinking, untrammelled by the need to reference others. Left to myself, I might have reached much the same conclusions about natural rights. But this is a work of intellectual history as well as philosophical argument. My main concern is that, while the author draws a clear distinction between the historical concept of natural rights (which he rejects) and the modern concept of human rights (about which he is more ambivalent) his criticisms of the former spill over into his criticisms of the latter.

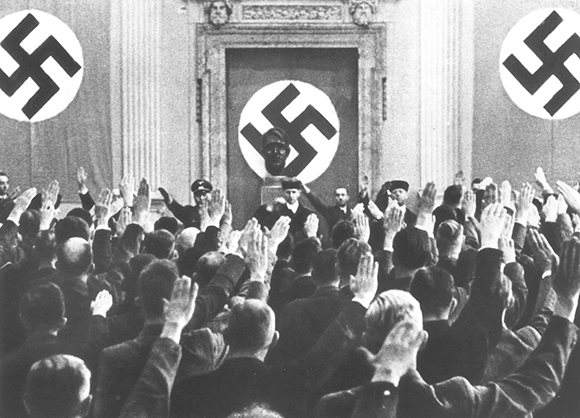

Biggar begins to get to grips with what he thinks about human rights only after the first six chapters. A human right, he has explained, “is a kind of natural right, since it is a moral claim that is supposed to be grounded in human nature or, more exactly, in the constant dignity that is the possession of every human being.” However, as Biggar recognises, human rights also have some of the characteristics of his paradigmatic legal right, being recognised and enforced in international law. After the Second World War, the international community understood that legal rights were not enough—everything the Nazis had done had been done according to their laws. There had to be some transcendent principles. Biggar could have made more of the fact that human rights are also recognised and enforced in the laws of many nation states—those that have written constitutions in which fundamental rights are given special protection and even, for that matter, in the United Kingdom, where the rights protected by the European Convention of Human Rights are also rights protected in UK law.

“Biggar’s principal target is what he calls a certain ‘rights-talk’—but it takes him a while to get there”

His first question is whether there are absolute rights. Taking torture as an example, he concludes that there should always be an absolute legal right against torture, even though in rare cases (the ticking bomb example) the non-consensual infliction of pain might be morally permissible and thus deserving of lesser sanction: a conclusion virtually identical to that reached by the Supreme Court of Israel. His next question is whether human rights are universal, addressing African and Asian critiques of western individualism. He concludes that the west is more communitarian than the east may recognise and the east is more individualistic than it recognises, so there is nothing wrong with the idea of universal human rights. But there is scope for debate about their content and there is sometimes a need to compromise (even the rights of women in Iran or black people in South Africa) for the sake of stability. The Rwandan gacaca courts are his main example of the need to tailor rights to realities on the ground and I have some sympathy for the view that the best (more properly the ideal) can be the enemy of the good. He also asserts—surely correctly—that the exercise of our legal rights is subject to moral duties and perhaps more controversially, “one of these is the duty not to alienate other people by slaughtering their sacred cows for trivial or unnecessary reasons”(he has the Charlie Hebdo cartoons in mind).

He moves on to a critique of David Rodin’s theory that the right to life can only be forfeited through voluntary and culpable wrongdoing. Biggar believes there is such a thing as a just war, where the innocent soldiers on one side must be allowed to kill the innocent soldiers on the other. His alternative is his own version of “double effect” reasoning: I may choose to do an act which I foresee will probably or certainly kill you, provided that this is not an effect which I intend (in the sense that I want it above all else), that I have striven to avoid it, and I have a proportionate reason to cause it. His point is that it would be better not to talk of a natural moral right to life but rather to talk of the circumstances in which it might, or might not, be “right” to kill an individual. Once again, “a right” and “right” are not the same thing. Agreed.

I expect that the lawyers (and politicians) among Biggar’s readers will only really get interested when they eventually arrive at the last three chapters. “What’s Wrong with (Some) Judges? (1)” mounts an attack, largely derived from the Policy Exchange reports The Fog of Law (2013) and Clearing the Fog of Law (2015), after the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights in Al-Skeini v United Kingdom (2011) and Al-Jedda v United Kingdom (2011), and of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom in Smith v Ministry of Defence (2013). All arose out of the conduct of military operations in Iraq. In Al-Skeini, the House of Lords (then the highest court in the UK) had held that Iraqis injured in the course of military operations in Basra while it was officially, but not actually, under UK control were not “within the jurisdiction” of the UK for the purpose of the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Court of Human Rights then held that they were. In Al-Jedda, the House of Lords held that the UK was entitled to detain civilians under a UN Security Council resolution even though this would otherwise contravene the European Convention. The European Court of Human Rights then held that the UK was not so entitled.

As a member of the House of Lords appellate committee on each occasion, I am sympathetic to the criticism that Strasbourg’s decisions expanded the concept of “jurisdiction” way beyond what the parties to the Convention had intended and failed to recognise that the obligations in the Convention were not designed to cater for armed conflict outside the territory of the member states. But I see these as examples of Strasbourg getting things wrong, rather than over-zealous rights-fundamentalism or a failure to vary the scope of Convention rights “according to morally significant facts on the ground.” I say that because Strasbourg has now significantly changed its stance, holding in Hassan v United Kingdom (2014) that the Convention rights do have to be modified to take account of the reality of armed conflict abroad. All of this is explained at length by Lord Sumption (with whose judgment I agreed) in Al-Waheed v Ministry of Defence (2017). This chapter would have been more powerful had the author relied less on the Policy Exchange reports and more on some up-to-date legal scholarship.

“What’s Wrong with (Some) Judges? (2)” mounts an attack upon a supposed “progressive zeal,” which moves some judges “to exploit the room for creativity granted by abstract concepts, in order to invent novel rights.” The focus is the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Carter v Canada (Attorney General) (2015) that the absolute prohibition on helping a person who wants help to die is contrary to the Canadian Charter of Rights. Biggar argues that such a difficult and controversial issue should have been left to parliament. There are indeed very good reasons why parliament is better suited to addressing such issues than are the courts. Judges do have to decide the case before them on the evidence before them; they cannot engage in a comprehensive study of the relevant facts and opinions; they are not accountable in the way that parliamentarians are accountable. But, unlike parliamentarians, judges have no choice. If a case is brought before them, they have to do their best with it. If their parliament has enacted a Charter of Fundamental Rights, which may well contain some rather abstract terms, they have to interpret and apply them; and if parliament does not like what they have done, there are usually (as there are in Canada and the UK) ways in which parliament can prevent or undo it. But the Canadian parliament has not done so and the decision has strong support from the Canadian public. I wish that the author could have acknowledged this and shown as great an understanding of the imperatives of judging as he does of the advantages of parliamentary decision-making.

“Unlike parliamentarians, judges have no choice. If a case is brought before them, they have to do their best with it”

His final chapter is devoted to “What’s Wrong with (Some) Human Rights Lawyers?” Three in particular are singled out in an attack on their “human rights fundamentalism”—professor Conor Gearty (London School of Economics), Baroness Shami Chakrabarti (formerly Director of Liberty), and the late Lord Anthony Lester QC. Readers will have to judge for themselves whether that attack is as fair to them as the author wishes they were fair to the government and what he sees as the public good. His attacks on (some) judges and (some) human rights lawyers would have been more powerful if they had been balanced by an account of some judges and lawyers of whose thinking he approves (and not just Lord Sumption, brilliant though he is). He might have started with the great Lord Bingham, who combined a deep understanding of human rights with an equally deep respect for parliamentary democracy and the business of government, and was for most of us the paradigm of a wise human rights lawyer and judge.

This account of what is wrong with rights, judges and lawyers, would have been a great deal more powerful if it had more to say about what is right about rights (including human rights), judges and lawyers. A little more Christian charity towards those with whom the author disagrees would also not have come amiss.