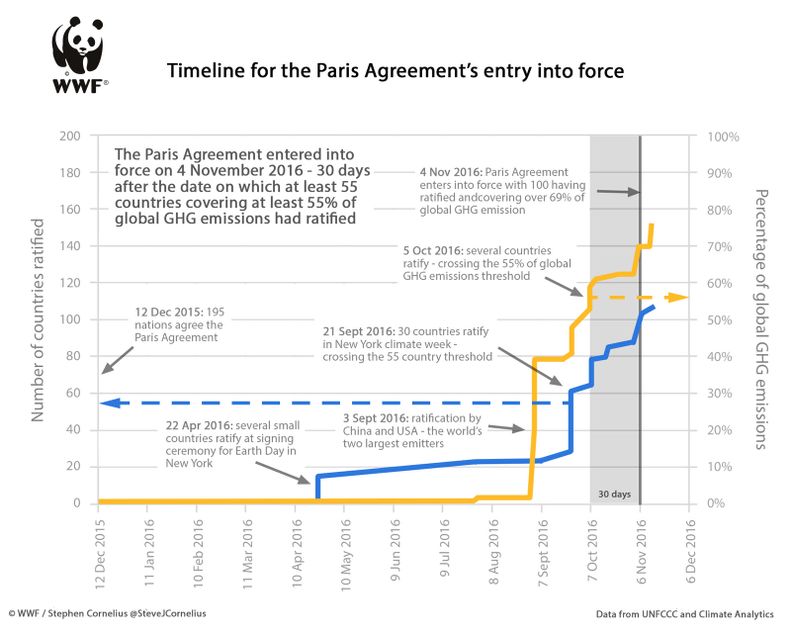

Scroll to the bottom for a Paris Agreement timeline

The Paris Agreement on climate change became international law on 4th November, much sooner than anyone imagined last December when the deal was struck. By that date 100 countries, accounting for more than 69 per cent of global emissions, had joined the climate action club by ratifying the Agreement—and more have done so over the past week.

UN climate talks taking place in Marrakech will see the birth of a new negotiating body to oversee the implementation of the Agreement and its five-yearly cycle to tighten climate targets. In itself, the Agreement does not go far enough to prevent further run-away climate change, and national pledges to date have been grossly insufficient. Indeed, the British government is yet to ratify Paris, although it has pledged to do so by the end of the year.

However, the framework agreed in Paris and rules being hammered out in Marrakech will still be hugely significant, in that global rules agreed by all participating nations will make the fight to limit climate change less susceptible to the political winds of individual countries.

In politics, the pendulum swings from one side to the other, but in climate science, it is moving in one direction. And that science is being taken seriously by people everywhere. There has never been greater momentum from businesses, cities and governments to engage in solving our climate crisis. This gives me confidence that the world will forge ahead together on ambitious action.

And in that context, the signs from Marrakech are encouraging. Countries have the same negotiating mandate today that they had on Tuesday and are getting on with what needs to be done under the rules of the Agreement. Outside the formal negotiation, the Global Action Agenda is showcasing inspiring projects such as the Africa Renewable Energy Initiative and the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, which covers over 7,000 cities.

Trump’s election has not weakened the resolve of participating nations, including China, Brazil and India, as well as the European Union, to press ahead with their own carbon reduction plans. This will create huge international markets in low-carbon technology, infrastructure and energy that any business-savvy administration would hesitate to walk away from. Since 2010, the UK government has sent mixed signals about its support for green energy. But it has also been the first industrialised nation to commit to phasing out coal use, has retained its landmark Climate Change Act and was a strong presence during the Paris negotiations. The UK should now seize the diplomatic initiative and reassert its role as the global cheerleader for green growth.

We do not yet fully understand how a Trump Administration will address the climate crisis and railing against the result of one—admittedly hugely important—election is not the answer to the global challenge we all face. Instead, the global community should come together as never before, demonstrating that a green industrial revolution can provide jobs, growth and security that is far beyond the capacity of an increasingly obsolete fossil fuel sector.

The Paris Agreement on climate change became international law on 4th November, much sooner than anyone imagined last December when the deal was struck. By that date 100 countries, accounting for more than 69 per cent of global emissions, had joined the climate action club by ratifying the Agreement—and more have done so over the past week.

UN climate talks taking place in Marrakech will see the birth of a new negotiating body to oversee the implementation of the Agreement and its five-yearly cycle to tighten climate targets. In itself, the Agreement does not go far enough to prevent further run-away climate change, and national pledges to date have been grossly insufficient. Indeed, the British government is yet to ratify Paris, although it has pledged to do so by the end of the year.

However, the framework agreed in Paris and rules being hammered out in Marrakech will still be hugely significant, in that global rules agreed by all participating nations will make the fight to limit climate change less susceptible to the political winds of individual countries.

In politics, the pendulum swings from one side to the other, but in climate science, it is moving in one direction. And that science is being taken seriously by people everywhere. There has never been greater momentum from businesses, cities and governments to engage in solving our climate crisis. This gives me confidence that the world will forge ahead together on ambitious action.

And in that context, the signs from Marrakech are encouraging. Countries have the same negotiating mandate today that they had on Tuesday and are getting on with what needs to be done under the rules of the Agreement. Outside the formal negotiation, the Global Action Agenda is showcasing inspiring projects such as the Africa Renewable Energy Initiative and the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, which covers over 7,000 cities.

Trump’s election has not weakened the resolve of participating nations, including China, Brazil and India, as well as the European Union, to press ahead with their own carbon reduction plans. This will create huge international markets in low-carbon technology, infrastructure and energy that any business-savvy administration would hesitate to walk away from. Since 2010, the UK government has sent mixed signals about its support for green energy. But it has also been the first industrialised nation to commit to phasing out coal use, has retained its landmark Climate Change Act and was a strong presence during the Paris negotiations. The UK should now seize the diplomatic initiative and reassert its role as the global cheerleader for green growth.

We do not yet fully understand how a Trump Administration will address the climate crisis and railing against the result of one—admittedly hugely important—election is not the answer to the global challenge we all face. Instead, the global community should come together as never before, demonstrating that a green industrial revolution can provide jobs, growth and security that is far beyond the capacity of an increasingly obsolete fossil fuel sector.