In January this year, the Church of England announced that it would create a new fund of £100m in reparations for the historic links between an 18th-century church fund, Queen Anne’s Bounty, and transatlantic chattel slavery. Queen Anne’s Bounty had large investments in the South Sea Company, which traded in enslaved people. Money from that fund—one of several pots that flowed into a central endowed fund overseen by the Church Commissioners, an internal body of the Church established in 1948 to manage its investments—was used to supplement the salaries of Church of England clergy. That larger endowed fund is currently worth £10.3bn.

It isn’t just that the Church profited from the slave trade. Some Anglicans were slaveowners, and the Church itself was complicit in the ownership of slaves and all that entailed. Slave owners often refused slaves’ requests to be baptised because they understood the liberatory potential of Christianity. Slaves found inspiration in the story of the Israelites’ escape from Egypt, passed along in oral tradition, and also Paul’s statement in his letter to the Galatians that “there is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female, for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” One Anglican clergyman in South Carolina devised a ritual in which slaves had to repeat an oath before they were baptised: “you do not ask for the holy baptism out of any design to free yourself from the Duty and Obedience you owe to your Master while you live.” Even after 1807, when the slave trade in the British Empire was abolished, missionaries produced versions of the Bible in which large portions of the Hebrew scriptures, especially the liberatory Book of Exodus, were excised, along with parts of the New Testament. Biblical passages encouraging loyalty to masters were retained.

In committing to establish this new fund, the Church of England has joined other institutions and organisations in the UK—including Lloyd’s insurance company and the Greene King brewers—that have responded to the calls for repair, both economic and in terms of broader restorative justice in the wake of slavery’s legacy. Such responses acknowledge that healing cannot happen without reckoning with, and making reparations for, that legacy, which lies behind ongoing systemic injustices for black people. But what do these new proposals amount to in material terms and what is their spiritual character—can they ever represent true atonement for the evil perpetrated in the Church’s name?

While the responsibility for this repair work belongs to everyone who has benefitted from slavery and the slave trade and the systems that they produced, churches have a particular calling to engage in this task because healing is central to the Christian message, with its commitment to take the actions necessary to effect true reconciliation between people. The summer 2023 report of the Archbishops’ Racial Justice Commission described the work of reparations as being a journey from lament to action. In a section written by Oxford theologian and commission member Anthony Reddie, the report states the hope that “institutions like the Church of England can set a prophetic lead to other Christian institutions, and beyond it, to other civic bodies and indeed governments.”

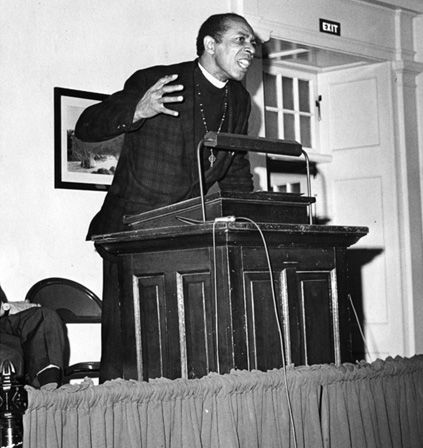

This was the kind of theological argument that some Black Power activists, including African American clergy, made in the US in the 1960s—and it is instructive to remember this history. Black nationalists such as Audley Moore, James Forman and Muhammad Kenyatta made powerful arguments in favour of reparations. Kenyatta argued that there was a strong and distinctive theological case for reparations based on the three Rs: repentance, restitution and reconciliation. African American clergy such as Paul Washington, Episcopal priest at the Church of the Advocate in Philadelphia, supported the case for reparations as a part of dismantling structural racism, and Washington hosted Black Power meetings in his parish. In 1969, his diocesan bishop, the white Robert DeWitt, responded to the demand from the Black Economic Development Conference for $500m in reparations (calculated at $15 for each African American in the US) from white churches and synagogues nationwide for their role in the injustices perpetuated through slavery and segregation. Most churches ignored the call, but DeWitt urged those in his diocese to contribute—and they did, raising more than $500,000, though his support for reparations wasn’t popular with everyone.

From this time onwards, Moore and other black activists were starting grassroots reparations movements all over the US. These would spread and grow and have international impact. An umbrella organisation, the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, emerged in 1987, and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People endorsed reparations in 1993. Bill Clinton, as president, came close to apologising for the slave trade while in Africa in 1998: “Going back to the time before we were even a nation, European Americans received the fruits of the slave trade, and we were wrong in that.”

A turning point was Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 2014 article “The Case for Reparations” in the Atlantic. Coates argued that 250 years of slavery, 90 years of Jim Crow and 60 years of “separate but equal” has led to moral debts of such magnitude that America is still haunted by them. He wrote: “It is as though we have run up a credit-card bill and, having pledged to charge no more, remain befuddled that the balance does not disappear. The effects of that balance, interest accruing daily, are all around us.”

Legislative change has been slow to come. The Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, known as House Resolution 40 (named after the 40 acres and a mule promised—but never delivered—to enslaved people at emancipation), has been introduced at every congressional session since 1989. Supporters claim it would now garner enough votes to pass. It calls for a commission to develop reparations proposals based on the role of the federal and state governments in supporting: the institution of slavery; forms of discrimination in the public and private sectors against freed slaves and their descendants; and lingering negative effects of slavery on living African Americans and wider society. In January, Democratic senator Cory Booker introduced a companion bill into the Senate. And in June this year, California’s Reparations Task Force published a 1,100-page report. It is estimated that about two-thirds of that state’s population support reparations (compared with one-third of the overall US population).

In the UK, Clive Lewis, the Labour MP for Norwich South whose family came from Grenada, has been especially prominent in the calls for reparations, saying that Britain cannot heal until it has acknowledged its slave legacy. In March he called upon Rishi Sunak’s government to enter into negotiations with Caribbean leaders on the issue, but Sunak refused to commit to such a course.

We cannot understand the way this debate is taking shape without noting that, among those reckoning with their legacies, the descendants of some of the wealthiest British slaveowners have been moved to action—notably through a recently formed group called Heirs of Slavery. Part of its purpose is to lobby the UK government to acknowledge and atone for the part it played in the transportation of 3.1m African people across the Atlantic, and to begin a programme of reparative justice. Members are also personally supporting a range of organisations in the UK and Caribbean, from university scholarship funds for black British students in the UK and Caribbean students at the University of the West Indies to the Pepper Pot Centre in west London, a day centre supporting elders from the Caribbean and African communities.

Members of the Trevelyan family are part of the Heirs of Slavery group. They have been both prominent and passionate in articulating their pledge to repair harms from their ancestors’ ownership of 1,004 slaves over six estates in Grenada. After finding their name in University College London’s database of slaveowners, they travelled to the Caribbean and made a public apology, acknowledging the cultural and financial advantages it had given their family. Laura Trevelyan, a former BBC journalist, has committed to advocacy work and promised £100,000 in reparations, funded from her pension payout after leaving the BBC. In the summer of 2023, the Gladstone family travelled to Guyana to apologise for its slaveowning past and announced its decision to pay reparations that will fund further research into the impact of slavery. Prime minister William Gladstone’s father, John, owned or held mortgages over 2,500 slaves, and made a fortune as a sugar planter in the British colony of Demerara, in present-day Guyana.

Like other slaveowners in Britain, the Gladstones and Trevelyans not only profited from enslaved labour but also received compensation from the British government’s Slave Compensation Commission after slavery (as distinct from the slave trade) was abolished in 1833. In the Trevelyan family’s case they were paid £26,898, while the Gladstones received the biggest compensation payment of all, more than £100,000 (about £10m in today’s money). Slaves received nothing and were forced to work for eight more years as unpaid “apprentices”. Eleanor Shearer’s recent novel River Sing Me Home evokes this dangerous and fearful period in the lives of supposedly freed slaves in Barbados.

It is salutary to remember that only in 2015 did Britain finish paying off the loan taken out in 1833 to compensate those early 19th-century slaveowners. This means that most people reading this article are likely to have paid some of their taxes towards that loan.

Although action groups for racial justice in various churches have been looking at these issues for a long time, the Church of England’s decision to establish a new fund had its origins in the mundane: internal questions asked in the Church Commissioners’ Audit and Risk Committee in 2019. The Church then initiated a study to understand the depth of its historic engagement in slavery. It was as a result of this that it proposed to set up the fund of £100m. The income from this fund will support grants used to address the “after-effects of slavery”, for example through educational projects, and especially in the West Indies and West Africa.

In May 2023, the Church Commissioners advertised for people with relevant experience to apply to join an Oversight Group for the new fund, and in July membership of that group was announced, with Rosemarie Mallett, the bishop of Croydon, appointed as its chair. Other members include experts in impact investing, historians, activists, journalists, legal specialists and one of the co-founders of Heirs of Slavery.

But is the Church making “reparations”? David Walker, the bishop of Manchester and deputy chair of the Church Commissioners, said when he announced the new fund that the Church Commissioners had chosen not to use the term “reparations” because they do not seek to compensate individuals, but rather to make amends for the past and work towards healing.

The summer report of the Archbishops’ Racial Justice Commission sets out three criteria for describing any such repair work as reparations: “Is the assistance named as reparations? Is it devised and run in conjunction with the victims? Does it include elements targeted at affected individuals?” If these three elements are not present, the report claims, “the work done will simply be another form of… ‘development aid’”. To avoid this, the response of churches should “go beyond benevolence and seek to address those power imbalances that are themselves part of the legacy of slavery.”

The warning against reverting again to paternalistic benevolence is important. Nevertheless, the term “reparations” has come to have a wide—and debated—meaning in recent years. Olúfẹ́mi O Táíwò, in his 2022 book Reconsidering Reparations, looks at concrete changes to our lives and institutions, rather than symbolic ones, and asks: what if building a just world might be reparations?

The very language of reparations resounds with theological meaning and recalls New Testament stories. When the rich man in the Gospel of Matthew asks Jesus how to gain eternal life, Jesus tells him to sell his possessions and give the proceeds to the poor. It’s not so much that rich people can’t be saved in the Christian system of salvation, but rather that if you gain something at someone else’s expense, you have to repair it: to heal what is broken, restoring it to good condition. We never find out what the rich man did, but in the Gospel of Luke, Zacchaeus the tax collector responded wholeheartedly to Jesus, deciding there and then to give half of his wealth to the poor and, if he had cheated anyone, to pay back fourfold what he had taken.

It was only in 2015 that Britain finished paying the loan to compensate early 19th-century slaveowners

The notion of reparations appeals also to the idea of “jubilee” found in the Hebrew Scriptures, in Leviticus 25, which entails the obligation to release slaves, forgive debts and repatriate property. At the heart of this notion is breaking the cycle of inequality by resetting the systems which perpetuate it.

When the archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, in his Easter sermon this year, discussed the Church Commissioners’ decision to set up this fund, and addressed the many letters he had received complaining about it, he said that income from the fund would “be used to help communities in this country and around the world affected by the fact that the Church Commissioners, in the 17th, 18th and early 19th century, invested in slavery. Some in fact owned slaves. And the living reality of Christ compels us to consider and respond to those actions that deny the reality of God’s power and love. It’s not postcolonial guilt, ambivalent wokery; it is the living presence of Christ, alive in our church and in our lives, who treats us all, high and low, important and unknown, exactly the same…”

It is regrettable that the archbishop felt the need to employ that dog-whistle term “wokery” when speaking factually of the historical legacy of the Church of England. And his appeal to the “living Christ” as the motivation for the work of repair may have been fitting in a sermon on the resurrection (it was Easter, after all), but it is not the theological language usually found in reparations talk. Nevertheless, if we are informed by the philosopher Táíwò in our understanding of the term reparations and place an emphasis on constructive action, then it seems to me that the Church is, in researching its past engagement with and financial benefit from slavery, and in setting up the new fund in response to learning that history, taking steps towards making reparations.

At the heart of any conversation about reparations is a need to look at the past so that we can see how it is influencing the present, in order to move forward. This is really a spiritual practice. In a church context (I am not saying this is the language for everyone), this practice could well tap into theological concepts of sin, grace and atonement. Think of the words of the hymn “Amazing Grace”, written by the former slave trader John Newton, with its famous lyrics: “Amazing grace (how sweet the sound) / That saved a wretch like me! / I once was lost, but now am found / Was blind, but now I see.”

In September 2019, the Virginia Theological Seminary in the Episcopal Church (the US branch of the Anglican Communion) announced the creation of an endowment of $1.7m. In its announcement it did not bypass the term reparations. The endowment is to be for “the payment of reparations, and the intent to research, uncover, and recognize Black people who labored on-campus during slavery, Reconstruction, and segregation under Jim Crow laws.” The endowed fund is “part of the Seminary’s commitment to recognizing its participation in oppression in the past, and commitment to healing and making amends in the future.” The seminary also noted that it hopes this will open up the possibility of reflecting on what it will take “for our society and institutions to redress slavery and its consequences with integrity and credibility.”

Earlier this year, Peter Jarrett-Schell, a white man who is the rector of a historically black church in Washington, DC, published Reparations: A Plan for Churches, in which he lays out both the spiritual resources and the practical steps for congregations and other institutions wishing to respond to calls for reparations. The book emerges out of many conversations, and early on Jarrett-Schell makes the point that “reparations is a process borne of relationship.” He outlines a process of six stages for anyone engaged in reparations, which begins with building relationships with the affected communities, moves to truth-finding and truth-telling, then repentance and reparations, and culminates in evaluation. This is a road previously unmapped, he notes, and no one has yet followed it to the end.

Not everyone in the Church of England likes the choice the Church Commissioners have made to set up a fund for—let’s call it what it is—reparations. The Save the Parish movement was especially upset that this was a new focus when Church of England parishes are struggling to survive. Soon after the fund was announced, the chair of that movement, Marcus Walker, published an open letter to the archbishop of Canterbury proposing that “before the Church can find £100 million for this new project, it needs to show that it can sort its own house out and fund its frontline.”

The very language of reparations resounds with theological meaning

This is an unfortunate framing of the matter. Save the Parish’s real complaint lies with the Church of England’s priorities in mission: that is, funding start-ups (church plants, to use the Church’s language), usually evangelical in style and belief, rather than supporting the tried and tested parish system. Funds could easily be diverted from such church plants to helping existing parishes.

The amount the Church will initially put aside for reparations is relatively modest and should not entail the Church having to make many, if any, choices between different causes. The £100m sum is less than 1 per cent of the Church Commissioners’ £10.3bn fund and will be taken from its income over a period of nine years, so that the original endowment remains untouched. The new fund will itself take the form of an endowment, so it will exist in perpetuity and will grow over time (and of course its capital cannot be spent). The income from the new fund will go towards “projects focused on improving opportunities for communities impacted by historic transatlantic chattel slavery,” as the Church Commissioners have put it. But because this is an impact investment fund, the hope is that the investment itself will go into projects for good and therefore drive change.

The new fund looks like a first step, the outcome of one piece of research on Queen Anne’s Bounty, and the Church of England has pledged to undertake further work. It will be paying close attention to calls from groups such as the Grenada National Reparations Commission, which has recently indicated its intention to bypass the British government and approach both the Crown and the Church directly.

If more money is put aside for reparations then the Church really will be making choices—and statements—about its values.