Every time a Morecambe & Wise nostalgia piece hits the airwaves, I twitch. Eric and Ernie offer the merriest of glimpses into the largely derided 1970s, and they remain the most successful double act in the history of British TV comedy. By the time they signed off their Christmas Day specials with “Bring Me Sunshine,” 30m smiley Britons were stretched out contentedly in the nation’s living rooms.

I watched, too, as a teenager in suburban Jewish northwest London—but with the exception of that one dazzling André Previn sketch (look it up), I didn’t get it. Was I alone? Should I have pretended when in company that I thought Morecambe and Wise were the pinnacle of comedic talent? Was my stony response a signal that I didn’t really understand most of my fellow Brits?

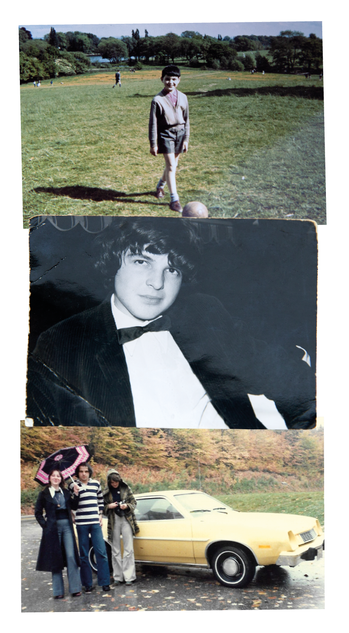

My parents were immigrants. My father had fought in the Italian campaign—at Monte Cassino, the bloodiest of battles—and my mother had come as a Swiss au pair to escape domestic complications. They were both decidedly patriotic, keen royalists and utterly respectable. But they weren’t much into Morecambe & Wise either. Perhaps you needed to have been part of a different Britain to get the gags.

I realise this last genuflection seems a little thin-skinned and ungrateful, especially since I was not a deprived child battling constant adversity.

Home cuisine was, thankfully for the period, decidedly un-British. I feasted on an endless supply of smoked salmon, in an era when it was very expensive, and Hungarian salami—all straight from my parents’ delicatessen. I don’t think as a child I ever ate a traditional Sunday roast. My parents never went to the pub and nor did I. They worked all the time: there were no family holidays, no weekend trips, no relatives in the UK to visit.

But for all my continental background, I felt patriotically British. My parents were grateful that they had found a better life here—and if my ¬parents were grateful, why shouldn’t I be? In my father’s case, long before the Nazis arrived to kill off most of his family in the Warsaw Ghetto, he had endured Poland’s brand of home-minted antisemitism. Northwest London was a substantial improvement. They believed straightforwardly—I would go so far as to say innocently—that Britain was as fundamentally fair and decent as they were, that the police and others in authority were incorruptible and good, and that democracy functioned satisfactorily because elections were properly run. None of this was, or is, to be sniffed at. Britain was nobody’s idea of an authoritarian state.

We were not, you may have guessed, a Guardian household but I was, in a mild way, a lefty. I once ruined my chances of a teenage romance when I refused to rouse myself from a sofa for “God Save the Queen” while watching the last night of the Proms with the (quite literally) upstanding family of the desired girl. It was hardly manning the barricades to support the revolution; I just thought it was ridiculous to stand up in someone’s living room for the national anthem.

The big British thing in my early teenage years was still the Second World War. It was the hugest of historical memories. And Churchill, dead when I was nine, was bigger than that. My father, with a million others, had queued all night to pay his respects in Westminster Hall.

I certainly thought England was mighty and that Britain, because it was bigger, was mightier—even if it was only England that had won the World Cup in what I did not then comprehend was a never-to-be repeated experience. And the Beatles. If any one thing defined the best of British, it was the genius of that lot. The fact that many on the right were sniffy about them, before they later joined in the veneration, reassured me that I had properly cool credentials.

But it was only when I left Cambridge for America in 1977 that other, important British attributes came into focus. I was at Harvard and then in Washington DC, so not exactly redneck territory. But even in liberal New England, the physical manifestation of American patriotism was ubiquitous and peculiar. The stars and stripes featured on cars, lawns, porches, schools. Every American sports occasion—then and now—featured the entire crowd standing and singing the “Star-Spangled Banner.” By way of contrast, in 1970s London neither the Union Jack nor the St George’s Cross featured very much, and football at White Hart Lane was embellished not by the national anthem but by the chant of “We hate Nottingham Forest.” I preferred the understated British patriotic style. For the first few months of my American stay, I found it easy to stride around with a sense of British superiority.

The wasteland of Times Square was genuinely shocking. Hotel rooms were equipped with prison-like grilles for security reasons. The noise was everywhere and constant. There was real menace in central Manhattan—not at all like Piccadilly Circus, which may have been drab and tatty but did not ooze violence. Despite at least some understanding of racial injustice in the UK, I was amazed by the total racial separation of the Washington DC supermarket checkout queues, more than a decade after Lyndon Johnson’s civil rights legislation. There was a lot of begging—and this too fell on racial lines. It all seemed neatly summed up by the then-famous John Kenneth Galbraith quote about America from The Affluent Society: “Here, in an atmosphere of private opulence and public squalor, the private goods have full sway”—and I made what I saw fit the quote. Britain’s public realm was shabby—I could see that—but it represented a conception of society that seemed, well, more decent.

I subsequently acquired a more nuanced view of America, but going there made me more patriotic. I took it on myself to defend Britain to Americans of all sorts, at a time when many of them, even professed liberal Anglophiles, thought we were going down the plughole. I found myself expounding, not with total conviction, the virtues of Jim Callaghan’s minority Labour government along with its so-called “social contract” with the trade unions, and vehemently defending the NHS and the British media. As for the difficulty in Northern Ireland, I was working for a Democrat senator at the time and explained to a bunch of police officers in deep-green south Boston, who saw me as a classic Englishman (at last), that the IRA was a murderous outfit and civil war would probably follow any withdrawal of British troops.

America taught me to appreciate the BBC—not only as a broadcaster but as something deeply, definingly British. Public service broadcasting (PBS) in America was a runt. In the world’s wealthiest society, overflowing with creative talent, public television had to devote chunks of primetime to the selling of branded umbrellas to fund itself. I listened to a lot of the BBC World Service—it gave me a competitive advantage in the senator’s office. For a start, I could pronounce Ayatollah Khomeini’s name accurately. In general its coverage was palpably superior to anything offered by American broadcasters.

And so when I came back as an aspiring journalist in 1979, I wanted to work for the BBC. I began instead as a graduate trainee in 1979 at ITV News (then ITN), on full pay during an 11-week strike—then a very British way of proceeding. But in the end I spent more than 25 years at the BBC, finally running Radio 4, the generator of the soundbite-cum-cliché “the BBC’s gone to the dogs but Radio 4 alone is worth the licence fee.”

I loved the Radio 4 gig, not least because it was so bound up with what I had consciously come to admire about one sort of Britain—the one that appreciates argument and debate, civility, culture, tolerance, respect and affection for language (well, our own language). I detonated a patriotic landmine. In 2006 I abolished the “UK Theme,” a sweet medley of well-known tunes from around the British Isles—Greensleeves, Londonderry Air, Men of Harlech, Rule Britannia and so on—that had opened the Radio 4 day at 5.30am for decades (musically arranged, as it so happens, by a Jewish immigrant). I did so to ensure that anyone tuning in at 5.30am would not go elsewhere for a bit of news and then forget to return to Radio 4. A few death threats followed—but such is the Radio 4 audience, they arrived complete with contact details. After 17,000 patriots signed a petition, a double-decker bus was hired to drive around Broadcasting House. About 10 people demonstrated outside. Tony Blair was asked for his view at PMQs. He very sensibly ducked. All in all it was a mildly mad, very stressful few days.

But in recent years it would have been far worse—any such decision would have been seized on and manipulated by Johnson’s government and its culture war hangers-on to attack the BBC for its allegedly feeble hold on “the nation’s mood.”

And therein lies the point about the idea of Britain. There are tens of millions of versions of Britishness—sometimes clashing, sometimes complementary. Outside wartime there is only rarely a clear, single national pulse. Nor is there any single expression of the national mood, nor a “national will,” nor anything that easily defines “national unity” or even “the national interest.” These are phrases largely blown around to aggrandise a particular view—whether they are used in the pub, a broadcasting studio or the cabinet room. Most of us are guilty of slipping in these potent two- or three-worders from time to time and I don’t wish to be prissy or absolute. There was, I concede, a national mood of sorts when Diana died, and after Aberfan, and around the London Olympics and Paralympics and Captain Tom. Three quarters of us have a positive view of the Queen, and the Platinum Jubilee was a big hit, and more or less all of us love David Attenborough—and that is fine and dandy. But on the whole the little phrases asserting national cohesion simplify Britain. They more often corrupt than they explain.

Politics—long before we had the identity-soaked arguments about Brexit and statues, the nature of the British Empire and the rest of the menu of our contemporary culture wars—was often about definitions of Britishness. The left-right, class-based debate on economics, redistribution and the role of the state that dominated the 20th century was also about competing versions of who we British were—and you could throw in your heroes and heroines for flavouring: Keir Hardie, Annie Besant and William Blake versus Disraeli, Margaret Thatcher and Edmund Burke.

I have my own unexciting preferences on these old-fashioned questions, but they often matter less to me than my view of the health of the institutions that together constitute what might be termed the rules of the game. And the game is a rather important one—namely the sustaining of a liberal, pluralist, tolerant democracy.

While it can be irritating, I accept that my fellow citizens will often differ with me on any number of issues. But I need to feel that the institutions shaping the debate and deciding what actually happens are constructed fairly, are good enough to do the job, and are capable of change when their weaknesses are exposed. I also believe that if they are good enough they should not be trashed. This should hardly have been difficult for a Conservative prime minister to understand, but Johnson was the trasher-in-chief.

The first-past-the-post Westminster electoral system provides a very particular duty, a patriotic duty, for those in power to protect institutions that are integral to our democratic wellbeing. Johnson, in his flailing around to hold onto power, referred to his “colossal mandate.” But we all know a minority of the votes cast in a general election can furnish any government, not just his, with a great deal of power. Hence the 1976 warning by Lord Hailsham, who became lord chancellor under Thatcher, of the danger of a British “elective dictatorship”—an over-powerful executive.

A concern and respect for the wellbeing of institutions that constrain power, rather than merely enable it, sits happily alongside a commonplace interpretation of 19th- and 20th-century British history, which suggests the reason we have avoided revolution, civil war and military defeat—endured in various combinations by all the other big European powers—is because our deep-rooted institutions, developed over centuries, have provided us with a golden mixture of individual liberty and political stability.

This sort of history is ridiculously simple, ignores the importance of geography and assumes Ireland is of no interest—but for all our complaining about parliament, the Cabinet, the monarchy, the civil service, the judiciary and the media, they are not so rotten as to have led to total collapse. And I suppose my emphasis on the importance of institutional solidity has a personal dimension too: 20th-century European Jewish history tells you vividly what true societal collapse looks like.

And now? Brexit certainly blew a hole in British understatement. Flags everywhere, I can live with that. MPs asking why there aren’t more flags in the BBC’s annual report? Ridiculous, though swatted away without too much difficulty by the director general. But the jingoistic boasting of the Johnson years has been dreadful and deadening, and has licensed others to puff up their chests and bellow and burp their own blather.

This was the gruel served up by Liz Truss in her first big speech as foreign secretary at Chatham House late last year: “People want to do business with Britain. They trust us. And they see things in Britain they would like for their own countries. They see that in Britain your background is no barrier to becoming a chief executive, a top footballer, or the mayor of London. They recognise we are a science and tech superpower, home to the third largest number of tech unicorns in the world. They know that we are an economic powerhouse, growing faster than any other G7 nation. From the Beatles to Sarah Gilbert to Tim Berners-Lee, we have unrivalled influence in the world.” (I winced at the Beatles reference, even though I know I have no proprietorial rights.)

Not all of what Truss says is untrue—although a civil servant should have warned her that anyone trying to dine out on Britain’s economic growth record is likely to get chronic indigestion soon afterwards. (The UK’s growth is forecast to be the slowest in the G7 next year, according to the IMF.)

But the overall effect of this sort of bombast is to devalue anything she said that might actually be right, and it brings with it the temptation of harmful overreaction from her critics, talking the country down simply because she talked it up.

Even if the constant hollering of the Johnson years has been offensive, that does not mean we should assume that every other country, by definition, is doing better than us, nor that the endless evidence-light assertions about Britain being “world-beating” simply must be wrong on no better grounds than that they came from this particular bunch of political featherweights. We do indeed have a lot of high-grade scientists, a lot of good universities, a high-performing set of creative industries. We have done some good things on climate change, we have outstanding museums, miraculous public transport in London (but not elsewhere), and so on. And although the prime minister’s projection of himself as a champion of liberty was typical Johnsonian hogwash, his three years of institutional destruction have not turned Britain into a place where you have to fear the knock on the door.

But he did not respect or understand democratic constraints. Leave aside Johnson’s limited comprehension of how the rule of law applies to him and his chums, and look at how he tried to use prime ministerial power to narrow British pluralism—including the mercifully unsuccessful attempts to install Paul Dacre as chair of Ofcom and insert Charles Moore as chair of the BBC. Look at the attacks on the judiciary. Governments have for centuries had trouble with the courts but now we are to believe “lefty lawyers,” in itself a deeply horrible term, are acting not for their clients but against—watch for another slippery phrase—“the public interest.” Look at the desire to diminish the authority of the Electoral Commission. Or the objection to too much noise from protesters. Or the use of patronage to corrupt the distribution of government contracts. Or the way the appointments process for arts organisations is being used to promote Conservative donors or ideological soulmates. It’s a long and baleful list.

Despite my innate suspicion of fake national unity, I recognise—with sadness—that millions have genuinely loved Johnson’s version of Britishness. But in the end, if there is a national interest, it comes in sustaining democratic institutions and procedures. That means Johnson’s collapse is a boon to my own patriotism.

Being British in the Johnson era has for much of the time been a matter of resigned acceptance. It should not be like that. There is joy to be derived from Britain’s rich—and getting richer—range of cultures. Note the plural. And I have long been sure enough of my own particular sense of British identity, with or without Morecambe & Wise, to say: the Johnson government’s version of Britain was not for me.