“It’s time we admitted that there is more to life than money, and it’s time we focused not just on GDP but on GWB—general wellbeing… It’s about the beauty of our surroundings, the quality of our culture, and above all on the strengths of our relationships.”

So which of our political leaders said that? Hard to guess, perhaps, because it sounds suspiciously like the sort of thing politicians of all hues say when (in office) they are failing to deliver economic growth, or (out of office) wanting to play down their opponents’ success in doing so.

But listen on. “Improving our society’s sense of wellbeing,” continued David Cameron (in 2006), “is, I believe, the central political challenge of our times.” How, as Prime Minister, has he met that challenge? Has he put “wellbeing” at the top of the agenda? Has he made it the yardstick against which he asks to be measured by voters this May? And if so, why aren’t we hearing more about it from Cameron in this campaign?

It’s the last question that is the most puzzling, since, despite all the talk of gloom and austerity, the wellbeing indicators actually tell a modestly but consistently positive story.

To be fair, it was the Prime Minister who ensured that there is a story to tell in the first place. Early in his premiership, he took the crucial first step of asking the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to measure, systematically, the wellbeing of the United Kingdom. Since 2011-12, the ONS has tracked four different measures of personal wellbeing: your overall life satisfaction; whether you feel your life is “worthwhile”; your level of happiness; and your level of anxiety. The ONS also tracks other measures of national wellbeing, including environmental and economic factors.

It’s not hard to see why, to begin with, Cameron didn’t try to make too much of a song and dance about this. Not only was the data new, and lacking in points of comparison, but with GDP declining, no one would have been listening to the offer of alternative measures of success. And since economic factors clearly influence wellbeing, even if they aren’t the whole story, the well-being data might not have been much to sing about either.

Read more on wellbeing:

Wellbeing rhetoric hides the truth

A happiness guru on wellbeing and fatherhood

What is well-being?

But now the recovery is well established, and we have three years of wellbeing data, it’s surely worth raising the question, what do they tell us? And others are raising it, too. International interest in using wellbeing as a measure of policy success has been spreading rapidly. The majority of OECD countries are now collecting wellbeing data regularly, and soon we should have high-quality annual data for all EU countries, and many more OECD members.

The report of the Legatum Institute’s commission attracted interest across the political spectrum. There is now an All-Party Parliamentary Group on Wellbeing. The coalition government set up an independent body, the new What Works Centre on Wellbeing, to assess the evidence and gather new information to ascertain which policies have most impact on wellbeing. The centre, which will be chaired by Paul Litchfield from BT, will focus particularly on the question of how to raise wellbeing at work, and its impact on productivity.

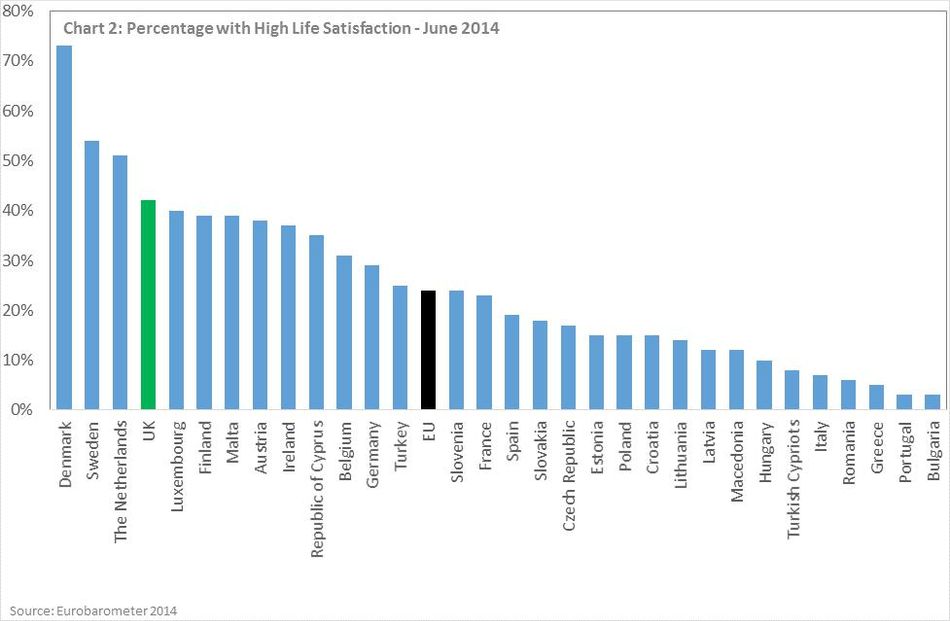

Figure 1: Percentage of people expressing high life satisfaction in selected countries: June 2014

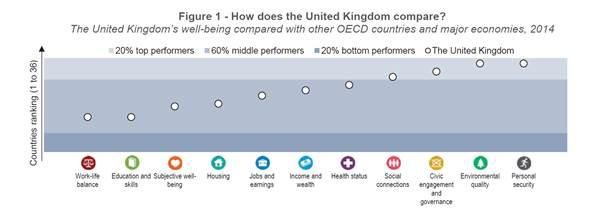

However, Figure 2 adds some light and shade to the picture. While most of our scores on indicators of wellbeing were above average, and we do particularly well on personal security and environmental quality, we do comparatively badly on education and work-life balance.

Figure 2: The UK’s comparative position on quality of life indicators, 2014

International league tables of what are, essentially, subjective indicators have to be viewed with caution. So it may be more telling to look at the trends over time within the UK than try to make big and possibly misleading cross-cultural comparisons. Is wellbeing increasing in the UK, or is it in decline? The survey responses collected by the ONS since 2011 are remarkably consistent, and will be, to some, quite surprising.

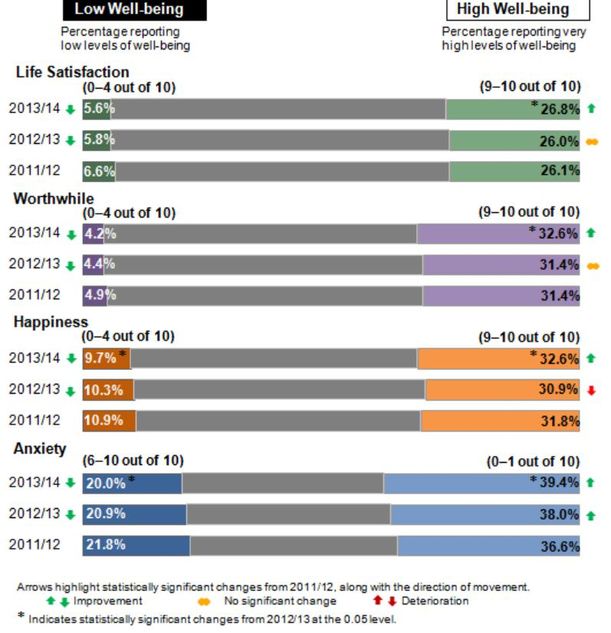

The ONS data suggest that, over this three-year period, there have been small but significant improvements in average personal wellbeing ratings in each of the four parts of the UK, and that improvement shows up in all four measures of wellbeing. On each of the four measures, too, there has been an increase in the proportion of people reporting the highest levels of personal wellbeing.

Interestingly, the greatest gain has been on the anxiety score. The proportion of people in the UK reporting very low levels of anxiety grew between 2011-12 and 2013-14. And again across all four measures, the proportion of people in the UK rating their wellbeing at the lowest level fell over this period. Figure 3 below provides some of the detail

Figure 3: ONS well-being responses: 2011-12 to 2013-14

So why has wellbeing increased? Causal analysis of the data is still pretty primitive. But the first thing we can say is that it's probably the economy, stupid. The older, and cruder measure known as the “misery index”—the sum of our unemployment and inflation rates—is at a 40-year low. Consumer confidence is above its pre-recession levels. In addition, satisfaction with public services has remained remarkably high despite the reductions in spending. But the high scores on personal security suggest some other factors are at play—for example, the dramatic fall in crime reported last, with the National Crime Survey for England and Wales reporting a 11% decline in incidents to the lowest level since the survey began in 1981, and (possibly more telling).

Wellbeing has already played a modest part in the election debate. To judge by the hustings convened, on 24th March, by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Wellbeing, all parties are converts to the cause. For the Liberal Democrats, Paul Burstow stressed the link between mental health—a spending priority for his party—and measures of wellbeing. Nick Hurd for the Conservatives and Helen Goodman for Labour both spoke strongly in favour of the concept.

Read more on wellbeing:

Wellbeing rhetoric hides the truth

A happiness expert talks fatherhood, purpose and how politicians could make us feel better

What is wellbeing?

Seek happiness and you shall not find it

Rupert Read, the Cambridge Green Party candidate, wanted to promote wellbeing as a target to the extent of abandoning the collection of GDP numbers altogether, but none of the major parties go that far, and nor would public opinion let them. But there seems to be some broad agreement that wellbeing would provide a better, more coherent framework for policy-making that must embrace far more than economics, and so it would be good to see this feature more strongly in the campaign.

In May, however, the debate will matter less to the politicians than the results. For then the key question will be: does wellbeing drive votes? There are some vital clues to the answer in a piece of research recently published by George Ward, Is Happiness a Predictor of Election Results? Using Eurobarometer data for many countries across a number of years he finds that, controlling for other factors, the electorate's subjective wellbeing is able to explain more of the variations in the vote share achieved by governing parties than any of the three main macroeconomic indicators (unemployment, GDP per capita and inflation).

Politicians have long been aware that output and inflation are not very good vote predictors (in fact, real personal disposable income has been a better economic guide). But Ward’s work suggests that a wider measure of wellbeing, including but not limited to economic factors, will give more powerful results. But as with GDP, the linkages are not straightforward. Governments get the blame for declines in GDP, which therefore harm incumbents’ voting shares, while the electorate is less inclined to give them the credit for increases in GDP.

This now well-established feature of economic cycles provides a political, as well as an economic, rationale for avoiding booms and busts, even at the cost of having to accept a lower average growth rate. Now, Ward argues that the same asymmetry in blame and credit applies to wellbeing, so that positive changes have a weaker effect on voting than negative ones do.

The rise in wellbeing should give Cameron some grounds for satisfaction that he started collecting the data, and encourage him to be bolder in pursuing this “challenge” and raising its profile in the election campaign. It should also give him some grounds for electoral cheer. But only some. However consistent the rise in wellbeing since 2011, it is still only modest. And the diluting effect identified by Ward suggests that once voters have taken personal credit, there’s only a bit of happiness left for the ballot box.