The Timca is a container ship that delivers cars to Finland and paper to Belgium, alongside other goods in both directions. The 28,000-tonne, 205-metre-long ship repeats this journey across the North and Baltic Seas with just minor variations throughout the year. It takes delivery of its cargo at one port and drops it off at another.

That’s the short version. It may make it look like a simple endeavour, a boring one, even. But the Timca’s eight-day delivery cycle is vastly more complex than it first appears—and the thousands of ships like it are the unnoticed worker ants of our global economy.

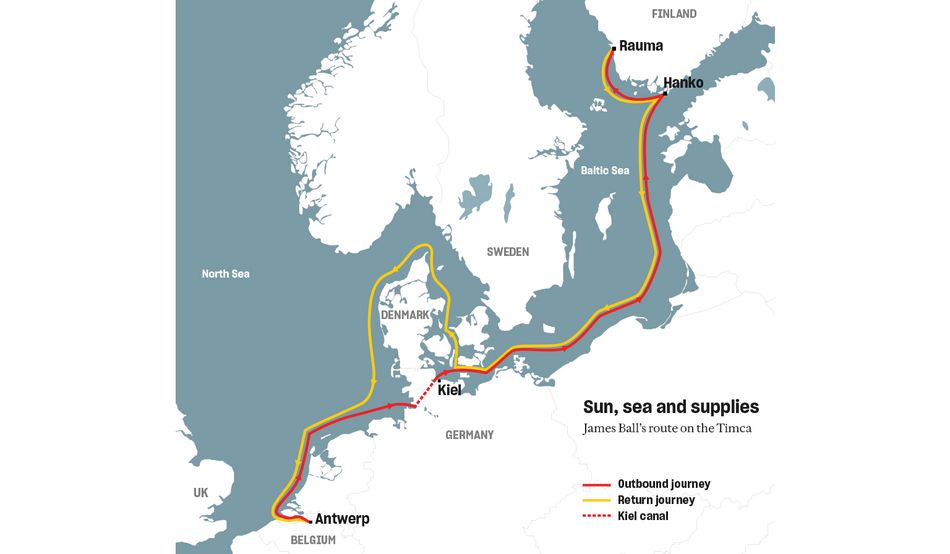

The Timca runs from Belgium to -Finland, but flies under the flag of the Netherlands, with a crew of Filipino sailors overseen by mostly Russian officers. To navigate out of each and every port, it must take on a specialist pilot. It has to decide whether it is quicker and cheaper to take the Kiel canal across Germany, or to sail around the Jutland peninsula (which contains parts of northern Germany and Denmark)—burning fuel at a rate of about four tonnes per hour.

In winter, as the Baltic Sea freezes, the Timca must contend with ice floes around Finland. All year round, the crew has to manage the cargo, keeping -potentially flammable loads away from combustible material, keeping track of chemically hazardous freight, and so on. What might seem at first to be a simple undertaking—sailing from one place to another—turns out to contain layer after layer of complexity, and also of brutal efficiency: every chance to strip out some cost is taken, every opportunity for revenue is seized.

It’s this that lets me witness the workings of the Timca firsthand. When the ship was built in 2008, it was designed with a handful of cabins to accommodate the drivers of container lorries, which can “roll-on, roll-off” the ship without the need to lift off the container or even detach the cab. But these cabins don’t get much use, as it turns out—it’s usually much cheaper to hire different drivers at each end of the journey than it is to pay to transport a driver for three days on a ship.

That means that there are a handful of cabins on the Timca’s mess deck not generating any revenue. In the ruthlessly efficient world of modern shipping, that doesn’t happen where it can be avoided, and so the Timca takes passengers.

This part of the process is perhaps the most old-fashioned aspect of everything the ship does. Where most modern travel starts with a convoluted online booking system, travelling on a cargo ship involves entering into email correspondence with a semi-retired commercial shipping executive called Colin Hetherington on the Isle of Wight.

The aftermath of Covid-19, a series of shipping disasters and near-misses—including the Ever Given running aground in the Suez in 2021 and the MV Dali’s collision with the Francis Scott Key bridge in Baltimore last year—and ongoing pirate activity in certain regions have made taking passengers more trouble than it’s worth on most routes. But Hetherington is still able to arrange eight days of travel on the Timca in the relatively calm and safe waters of Europe, from Antwerp to Rauma, Finland and back, including meals, for around £900.

The process of getting aboard the Timca resembles nothing else in international travel. Equipped with a few bits of paperwork—and a guarantee that your travel insurance includes the costs of repatriating your body, should that be needed—you are directed to report to a police -customs point around half an hour’s journey from the dock proper. After a cursory look at your passport, you’re free to make your own way to the ship.

The process is somewhat confusing. In my case, I took a taxi to the entrance of the harbour, waved it off and put on the high-vis jacket I’d been told to bring along. I then introduced myself to a guard on the gate to the dock, who told me I wasn’t allowed to walk to the ship and that I should have insisted the taxi entered the dock complex. This standoff was navigated by virtue of my standing there being obviously useless for sufficiently long enough that the guard took pity on me, driving me there himself. He dropped me a few yards from the Timca—a vast vessel, easily dwarfing everything else around it. A large ramp led to the interior of the gleaming white ship, reminiscent of the inside of a multistorey carpark, as containers were deposited onto the deck far above.

Souped-up forklift trucks were whizzing back and forth from the vessel. Each one carried a single shipping -container and dropped it next to a crane, which then loaded the containers onto the ship. As this went on, dozens of cars— on this occasion, mostly Peugeot 3008s—were being individually driven onto the lower decks. And in the middle of this hustle of considered and practised activity was me in my high-vis jacket, -wandering confusedly towards the cargo office (which, I noticed, was protected by -explosion-proof glass).

After a few minutes of polite waiting around, an out-of-breath crewman—who’d just done the trip three times in a row for the other passengers—escorted me through a baffling series of narrow ship’s corridors and up five flights of stairs to my cabin, No 618, on the mess deck. No security checks, no IDs, no paperwork, no nothing: a spot on the ship was mine. I had a small sofa, a table, two bunk beds, a -wardrobe and a mini-fridge to call my own, and even a window with a view out to sea.

Cruise passengers would pay through the nose for such luxuries, I was told. Across the way was the drivers’ (now -passengers’) mess room, which I shared with the other four passengers, equipped with various comfortable chairs, an -antiquated TV set, a -Nintendo Wii and a dartboard. This would be all the available entertainment for the next week and a bit.

Despite the apparent efficiency of the loading process, it takes hours, and because passengers need to be safely out of the way during a busy time, we are largely confined to the deck, with only a small smoking area next to an external staircase from which to get air or watch what was happening. But then, very late at night, the Timca is finally guided out of port by a pilot, and then down the river to the North Sea.

The next day, we are able to come up to the ship’s bridge, three floors higher. (The crew deck is immediately above us, and the officers’ deck above that.) From this vantage point, it quickly becomes clear that the huge, empty sea you see when looking out from the shore isn’t really so empty after all.

Either a quick look at the radar screens, or simply out of the windows all around us, reveals ships and boats in every direction, following the shipping lanes and local routes. Smaller fishing craft do their thing, crossing the lanes between large ships like ours. Offshore windfarms and oil rigs are a frequent sight. We have harnessed the North Sea almost as much as the land—humanity has put this space to work, and it teems with activity. A sea of tranquility this is not.

The technology is a steampunk-esque mix of old and new. There is a hand-written logbook, updated by whoever is on watch. A dot-matrix printer rattles off incoming warnings. There are various alarms and buzzers, as well as computer screens and navigation aids. But there are still dozens of pigeonholes full of the various flags still used for signalling.

We’re told we have the run of the bridge—the action centre at the very top of the ship, from which the officers chart its course and run its operations—provided we follow one simple rule. “Don’t touch any red buttons,” third mate Evgeny warns us, as he fills us in on the basics. Evgeny used to fish snow crabs in the Bering Sea, but climate change brought warmer water, which caused the snow crab population to collapse, so now he’s in shipping.

Timca is a European ship in European waters, but most of its crew is from the Philippines. This is extremely common, as few Europeans will work for the wages on offer. Of the officers, most are Russian, though the chief engineer is Estonian. Everyone speaks in English—this is a requirement on most commercial ships—and no one discusses politics while at sea.

The entire ship is staffed by a crew of 20 people. Some work as engineers, the officers work on the bridge, many of the rest take care of cleaning and maintenance—some just wipe down the ship, which is pretty spotless—and there is one cook -looking after the crew and passengers.

Having previously worked on a cruise ship with 2,000 passengers, the ship’s chef tells us that serving 20 crew and a handful of passengers now and then is a cinch. The food onboard is good, though it is served at fixed (and unusually early) times: a standard continental breakfast is on the table at 7am, lunch at noon, and dinner at 5pm, with bread to toast and a few snacks left out in between. There’s no choice—passengers get something -similar to what the crew and officers get—but on different nights we get chicken in a mustard sauce, steak frites and a decent curry with rice. The crew work seven days a week, mostly on split shifts, working four to six hours of every 12. Each staffer works eight weeks on, eight weeks off, but they rotate at different times, so the make-up of the ship is always changing. Not everyone knows each other well.

More strikingly, no one on board knows exactly what the ship is carrying. It’s not hard to spot the cars—but the contents of the sealed metal containers stacked on the main decks are a mystery. What is apparent is how every bit of space is occupied: even the ramps leading up to the decks have been used to house -unusual loads. The main loading ramp has been used to strap down a large tractor that looks like something Jeremy Clarkson would covet.

Instead, the crew gets a sheet explaining which containers have hazardous loads—“There’s nothing explosive on board this time,” Evgeny reassures me with a smile—and spaces it out accordingly (everything at sea is subject to strict international regulation). Some cargo has to be plugged in to be kept hot or cold, a service for which the owner pays extra. Otherwise, all anyone on board needs to know is which box goes where.

The Timca is heading towards Hanko, the southernmost port of Finland, a -journey that will take around three days, given the ship’s top speed of about 22 knots. For the journey there, it is heading towards the Kiel canal, which allows it to cut off the entire Jutland peninsula.

The ship’s captain is not particularly enthusiastic about this part of the route. Though the canal route cuts hundreds of miles off the journey, it is painfully slow. The ship has to navigate locks, as well as -waiting first to enter the River Elbe, and then the canal itself.

Each of these, like every harbour, requires a specialist “pilot” to board and navigate the ship while it’s in their waters. The pilot, knowing the waterway better, can safely navigate in the confined and busy space. It is one of the best-paid jobs in shipping, but one of the most dangerous, not least because it involves getting on and off moving ships in the water.

The Kiel canal, which is entirely contained in Germany, is one of the busiest shipping canals in the world, carrying more vessels each year than either the Suez or Panama canals (if not anywhere near the same tonnage of freight). But despite that, it runs at a loss and has for many years. The explanation for this turns out to be simple, but I only learn it on our return journey.

First, I come to understand the captain’s frustration, as it takes the ship more than 16 hours to travel 61 miles along the canal. The time lost to delays at the canal are hard to make up once we’re out the other end: even when back at top speed, the ship is still slow. At the time of year we’re travelling, when the sea is still clear of ice, it’s a -straightforward onward journey across the Baltic Sea to Hanko—but still a long one.

Hanko is a small town with a supermarket, a café, the kind of tiny cinema that died out -elsewhere long ago, and not much else. The town’s harbours are the only reason Hanko, and its population of around 8,000, are here.

Hanko was founded in 1874 because Finland needed a solution to famine—a recent one had killed one in 12 of its -population—and that meant establishing an ice-free port that could import -essential supplies. Hanko’s founding centred around getting a railroad as far to the south of the country as possible, and building a harbour and a settlement there, while finding somewhere in the United States to build and ship the actual trains. It failed and went bankrupt at least once along the way, but eventually the effort was successful.

Most of the cargo is unloaded, and the almost-empty ship navigates to a larger Finnish town called Rauma. This looks on the map to be a simple journey of around 150 miles, but in reality it is much longer, because it requires navigating a safe route through the archipelagos off -Finland’s southwest coast, which are made up of tens of thousands of islands.

The autonomous Åland Islands are ostensibly governed by Finland. The -people there speak Swedish, and -Russia is one of the guarantors of a long--established accord banning any -military -presence there. With relations between Russia and its Nordic neighbours -worsening—especially now that Finland and Sweden are members of Nato—the islands are an increasing source of -concern, not least because anyone -taking control of them could also control all shipping in the region, as well as crucial energy and communications cables. Tensions in the Baltic are at a high after the severing of multiple crucial communications and power cables in recent months—leading to the daring seizure of a Russian ship by Finnish authorities in December—meaning it is far from guaranteed that this journey will remain a boring one.

But for now, at least, it’s smooth -sailing. Rauma is where the Timca picks up the main cargo it is taking back to Antwerp: paper, and lots of it. Finland’s forests -supply much of Europe’s paper, from -toilet roll to high-quality book and -magazine printing (if you are reading this article in print, there’s a good chance the paper travelled this way). Rauma is a paper town: the paper plant supplies its jobs, generates its heat, processes its waste-water and more—and the Timca and its sister ships take that paper to the rest of Europe.

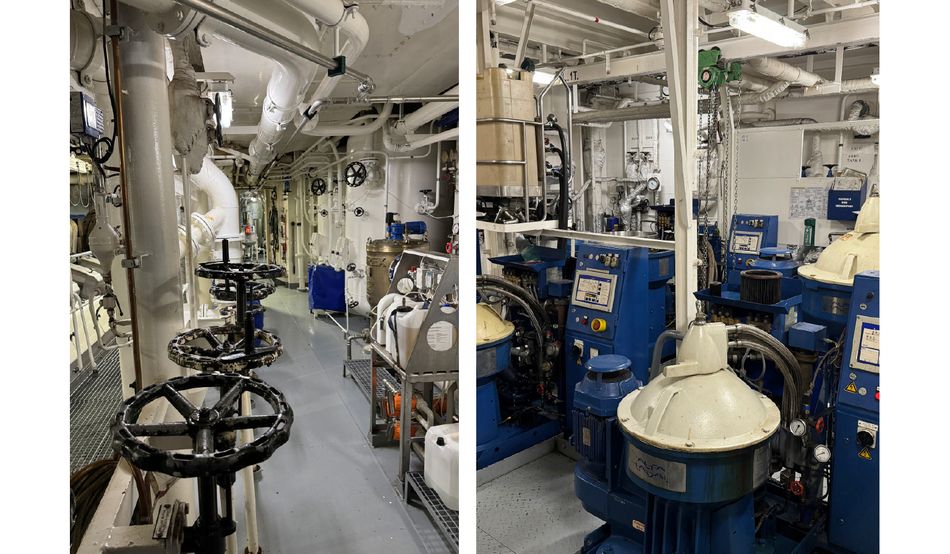

To do so, the Timca burns a staggering amount of fuel. Right down on the -lowest deck, the chief engineer, who goes by Elvis, shows us the two enormous engines that drive the ship forward and power everything around us. The room is -furnace-hot and the engines themselves can melt the soles of shoes if engineers don’t move fast enough. It is loud enough that everyone is wearing ear protection.

As Elvis explains once we’re somewhere quieter, the engines aren’t burning diesel. Instead, they’re burning heavy fuel oil (HFO), a thick, tar-like substance that is messy and difficult to use. It has to be heated before it’s used, or it won’t burn, and it is a filthy fuel—unsuitable for use on land.

Crucially, though, HFO is significantly cheaper than diesel, because it is essentially a byproduct of the -extraction of the lighter fuels. When you burn 100 tonnes of fuel a day, the savings are -considerable.

There is not a huge difference between the levels of CO₂ emitted by burning HFO and by burning diesel. HFO does, however, emit far more sulphur dioxide, which is responsible for acid rain.

For that reason, the ship is fitted with an elaborate system that sprays the fumes from the engine with seawater, to recapture most of the sulphur dioxide (the result of greater regulation). But nothing prevents the need to regularly turbo-wash the filthy fuel off the engines and their bearings. No-one said engineering was a glamorous job.

Everything the Timca does is honed towards efficiency and cost reduction. The goods we buy from across the world are affordable because of the net effect of each of these economies and efficiencies—the real cost of shipping is 95 per cent lower than it was a century ago, precisely because of numerous decisions few of us ever see, let alone think about.

The captain has made one of these decisions on our way back: we are going to sail all the way around the Jutland -peninsula this time, instead of traversing the Kiel canal. The water is extremely shallow towards the edge of the Baltic Sea, and a ship must have a draught—its depth below the waterline—of not more than 7.5 metres to pass safely, according to the crew.

The ship was more heavily loaded on the journey to Finland than on its return, meaning that we are now light enough to be able to take the long way round. Even with the cost of extra fuel, this makes it cheaper to avoid the canal altogether, and avoids the risk of further delays (though the shallowness of the water around Copenhagen sets off numerous loud alarms on the bridge).

This, as it turns out, is the reason the Kiel canal loses money while the Suez and Panama canals remain hugely -profitable, even despite political unrest. Taking a detour around the Jutland -peninsula adds 250 miles to a journey; by contrast, avoiding the Suez canal involves travelling up to an extra 6,000 miles, while for the Panama canal it’s an extra 7,000 miles. They truly have a captive market, and can charge ships much more to pass through.

The cheap and convenient food, clothes and household items upon which we’ve come to rely—all the stuff we buy daily without a thought—depend on the relentless operation of ships like the Timca, round the clock and throughout the year. Many operate in waters far more dangerous than these, where politics isn’t a matter of tensions or concerns, rather missiles are fired at ships or crews taken hostage. Still, the goods must travel, their operators squeezing out every last bit of profit as they do so.

It’s this that explains why such a huge ship will take its handful of passengers along, even though the fee each of us has paid amounts to the cost of about 30 to 40 minutes of fuel, at most. We are simply an extra bit of cargo, like the tractor left on the loading ramp. The chef is asked to keep an eye on us and cook a little extra food. We take up space that’s otherwise unused. Perhaps we’re even a little bit of diversion for the crew and officers.

But as we dock in Antwerp and the harbour crew scurry aboard the ship to start unloading, my fellow tourists and I walk off the ship largely disregarded—just another piece of freight to be dropped off before the Timca begins its cycle once again.