Gold may no longer back currencies but it has lost none of its allure. Astronomers recently added fresh lustre when they revealed that colliding neutron stars—as well as supernovae—are the universe’s gold factories. Less exotically, the disclosure that $300bn is tucked away in vaults in and around London appealed to our inner gold bug. But does it make any sense to invest in gold?

Even when the gold standard prevailed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the case for investing in the precious metal was weak. Gold was certainly a store of value. But the very backing of currencies by gold ensured price stability anyway. And if prices were stable it made better sense to secure yield rather than to hold an inert hoard of gold. In Jane Austen’s novels, written while Britain was off gold during the Napoleonic wars, it was income such as Darcy’s £10,000 a year rather than piles of guineas that was seductive.

Britain went off gold for good in 1931, removing the link established by Isaac Newton in 1717 which Keynes had disparaged as a “barbarous relic.” The Bretton Woods system of fixed but adjustable exchange rates which came into existence after the Second World War retained a vestigial golden underpinning since foreign central banks could exchange their holdings of dollars for gold at a fixed price of $35 a troy ounce (set by Franklin Roosevelt in 1934). But that final tie was removed by Richard Nixon in August 1971 when he ended the convertibility of dollars into gold, creating the current system of floating exchange rates with no underlying anchor.

Since the early 1970s, the case for investing in gold has been quite different. Gold has essentially become a commodity play in a world of fiat money. Investors must bear in mind the underlying retail demand for gold as jewellery especially in China and India, the two biggest markets, and the supply of gold from the global mining industry. But most of all they have to weigh up the speculative arguments for an investment that offers no yield and incurs safekeeping costs.

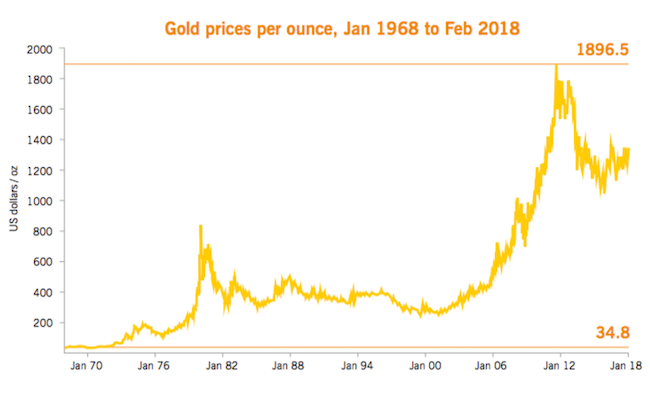

Those arguments are twofold. One is to invest in gold as a hedge against inflation. If prices are surging, gold represents a store of value that cannot be eroded. As Peter Bernstein, an investor and financial historian, wrote in The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession, published at the turn of the century: “In the frantic inflationary fevers of the late 1970s and early 1980s, frightened and even sophisticated people turned to gold from dollars.” Indeed the gold price soared to a peak of $850 an ounce at the start of 1980 during that latter-day gold rush, a breathtaking rise from its price of $35 a decade earlier.

But the case for holding gold in order to safeguard against inflation weakened as central bankers tamed the beast and governments introduced inflation-protected bonds. The gold-price peak in 1980 was short-lived once the recently appointed Paul Volcker showed his anti-inflationary mettle at the Fed. Inflation remained low under his successor, Alan Greenspan. By the end of the century, when the gold price had retreated to below $300 the mood was well captured in a New York Times headline: “Who Needs Gold When We Have Greenspan?”

The answer came a few years later as the financial crisis of 2008 shook faith in central bankers. In troubled times gold is a haven asset. The financial crisis was followed by the euro crisis of 2010-12— when investors faced potentially catastrophic losses if vulnerable economies such as Greece or Spain had to revert to their former (and devalued) national currencies, the case for holding gold remained persuasive. Those who adopted this strategy were well rewarded: gold touched an all-time high of $1,896.50 in September 2011.

If gold comes into its own when inflation is boiling and financial and political turbulence prevails, it is less attractive when prices are tepid and stability returns. Early fears that quantitative easing would kindle inflation have been allayed. Indeed “lowflation” has become prevalent in Europe and America despite the best efforts of central banks to coax price rises back up to their target of 2 per cent a year. As important, the threats first to western capitalism as whole banking systems came close to collapse and then to Europe’s stripling monetary union were successfully thwarted.

Since its highs earlier in this decade, the gold price has wilted as investors have preferred investments in equities, though recent corrections have cooled that enthusiasm. Despite political shocks such as Britain’s vote to leave the European Union in June 2016 and geopolitical tensions such as North Korea’s nuclear provocations, the strengthening global economic recovery has worked against gold. Britain might now appear to be an exception since inflation rose to 3 per cent in late 2017 where it remains. Yet this essentially reflected the effect of the depreciation in the pound following the Brexit referendum vote in hoisting import prices. Pay growth—the main domestic source of inflation—remains subdued despite low unemployment, in line with the experience of other advanced economies.

One further potential weakness for gold is that the precious metal may be supplanted by crypto-currencies such as Bitcoin, which have enjoyed a spectacular boom in 2017. Yet the recent sharp decline in values and worries about their use in the dark web and black economy are likely to restrain their appeal. Gold will remain the ultimate haven asset—a strength that will, however, be a weakness if the current benign combination of economic recovery and tame inflation continues.