In the first quarter of 2015, retail investors plunged more cash into property funds than into any other asset class; a year later they abruptly reversed course, giving the sector its biggest month of outflows since 2008. This merry-go-round is all too familiar in the world of property investment, where the temptations of both income and capital growth in upward markets are tempered by fears of crashes when the cycle turns.

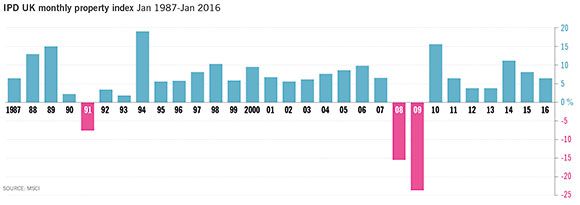

In the low-yield environment of recent years, real estate has looked especially attractive: according to the IPD index, UK property has produced annualised total returns of 13.8 per cent for the past five years. Real estate—the world’s largest asset class at £150tn—also offers diversification for those who invest mainly in equities and bonds.

Property equity funds hold listed companies such as British Land and Land Securities; international versions may also hold overseas firms such as the French shopping mall operator Klepierre, or Vonovia, a German residential landlord. Funds such as F&C Real Estate Securities or Premier Pan European Property, both favoured by Darius McDermott, managing director at the fund broker Chelsea Financial Services, hold a broad range of shares in real estate companies, with the ease and speed of trading associated with equity markets. But this also means they are less useful for diversification, since the shares are subject to movements in the equity market.

Directly invested property funds, which buy buildings themselves, do not move with the equity market. They come with their own pitfalls, however: they may use debt to enhance returns, but it can also amplify losses; buildings must be maintained and managed, resulting in costs that eat into investors’ gains.

Property funds are either open-ended or closed-ended. Many UK providers offer open-ended funds, which can raise as much money as they wish and tend to allow investors to ask for their money back at short notice: as short as one day, in many cases, even though it can take several months to buy or sell a commercial building. This too has a downside: fund managers may be forced to buy buildings when investors pile in and sell when they withdraw money, even if this leads to ill-timed transactions.

To cater for such circumstances, many hold a cash buffer, although this dilutes returns. Funds may also halt redemptions or switch to “bid pricing,” in effect charging investors a steep fee to withdraw cash. Several open-ended funds had to halt withdrawals temporarily during the financial crisis, although they still outperformed closed-end funds because they carried less debt.

Mark Dampier, research director at Hargreaves Lansdown, is sceptical of the merits of open-ended property funds, at least for retail investors. “You can have a brilliant fund manager who still gets totally screwed by the inflows and outflows of the fund,” he says. “One problem is that the average holding period seems to be about three years, whereas in commercial property I think you should be looking at 10 years for just about any fund.”

Closed-ended funds are usually real estate investment trusts (REITs) whose shares are listed on a stock market. Big REITs such as Land Securities carry out new property development, adding to their risks and potential rewards, but there are also trusts aimed squarely at income generation such as the UK Commercial Property Trust and F&C UK Real Estate Investments.

Is this a good time to buy commercial property? UK returns have probably peaked in this cycle, analysts say, but Darius McDermott said the asset class was “not about to fall off a cliff.”

Jason Hollands, managing director at the wealth manager Tilney Bestinvest, said: “The stellar returns over the last couple of years have been driven by capital appreciation, particularly in London’s West End and the City, which may have peaked. Therefore future returns are likely to be much more driven by income growth.”

The upcoming EU referendum is one reason many investors have turned sour on the asset class. Industry leaders such as Rob Noel, chief executive of Land Securities, have warned that a vote to leave would take an immediate toll on the property market. Such worries have left shares in companies like his trading at steep discounts to the value of their buildings. But if you believe the UK will vote Remain, or indeed disagree with Noel’s view of the effects of a Leave vote, this may look like a buying opportunity.

“We think there is still some money to be made in the sector, albeit lower returns than the past four years,” McDermott said.