Between October 2010 and April 2012, a quarter of a million people died in a famine in Somalia. Even in the war years, no one had seen dying like it. In a few weeks in mid-2011, half a million people abandoned their homes in the south of the country and walked across the desert to Mogadishu, an exodus of hundreds of miles marked for eternity by thousands of shallow graves. In the camps the survivors erected out of brushwood and plastic bags in the war ruins of Mogadishu, hundreds were dying every day. When cholera and measles swept the camps, that number accelerated into the thousands. The living and the dead soon found themselves competing for space. Mothers would return to the graves of children they had buried the day before to find a camp had materialised on the same spot over night. By the end of the catastrophe, one in 10 of the children in southern Somalia aged five and under was dead.

Maybe you remember it? Perhaps you gave money to the aid agencies who blanketed newspaper front pages and billboards in London with pictures of starving Somalis? The campaign was one of the biggest of the last decade, raising £1.2bn in months, about £400 for each of the three million Somalis in need. That figure, however, poses a question. With all that money, how did 258,000 people still die? The answers are an excruciating testament to how badly we in the west can get Africa wrong.

The truth about famine in Africa is that it hardly ever occurs. The Somali famine is the only one to have taken place in Africa in the 21st century, and it had its own special causes.

As was evident to anyone in Mogadishu at the time, even at the height of the famine in August 2011, very little aid was getting to the epicentre in southern Somalia. Almost none of the big western aid agencies raising money to fight the famine were even present, confining themselves to a secure compound at the airport if they were in southern Somalia at all. Why?

Aid workers talked about lack of funds, rich world heartlessness and their own frustrating safety protocols. To journalists familiar with disasters and emergency aid, that sounded all too plausible. It’s probably also fair to say that most of these aid workers, who tend to be well-intentioned and well-motivated people, weren’t lying so much as guessing.

Beyond the razor wire of the aid compound and out in the city, Somalia’s Prime Minister, its Defence Minister, its Minister for Presidential Affairs, one of its military advisors and a manager for a Somali aid group all knew why aid wasn’t getting through, and all spoke openly about it. They said that the Somali and United States governments were forcing aid agencies to withhold food from southern Somalia in order to put pressure on al-Shabaab, a small Islamist group allied with al-Qaeda. Agency managers had been persuaded to go along with this strategy because, according to the Americans, al-Shabaab sometimes stole aid. A case could be made that food aid was a form of support to a proscribed terrorist group, an offence which carried severe penalties under US law. When the aid managers objected, the US reminded them that it was their biggest donor. Reluctantly, the managers capitulated.

As a journalist, I was most outraged by the fact that so few people were aware of what was happening, or, as I later thought was more accurate, that so few were even able to imagine it. The Somali famine was testament to the robustness of our misunderstandings: the way we could look at Africa and still fail to see it. In contrast to their campaigns asking for money to assist the dying, the aid agencies could not help because they were not there, an absence that had helped to create the famine in the first place. But this was a reality so at odds with western preconceptions of Africa that it eluded almost every foreign observer. That’s not to say that I alone possessed the independence of mind to search out the truth. My fellow East Africa reporters were among the best in the business and I only stumbled across what was really happening by accident when the Somali aid group manager, exasperated by my own blithe assumptions of western compassion, took me aside and, over several hours of interview, set me straight. Years later, it turned out he was not the only aid worker who knew the real story. In 2013, Philippe Lazzarini, the UN humanitarian coordinator, began to change the official account of what had happened in Somalia when he said: “We should have done more. These deaths could and should have been prevented. People paid with their lives.” Oxfam’s Somalia chief went further, writing in the New York Times that the deaths of 260,000 Somalis “should weigh heavily on the conscience of Americans” since “US government counter-terrorism sanctions effectively prevented many humanitarian agencies from providing aid in the hardest-hit areas.” Those sanctions were the story, not some myth about Africans’ tendency to starve.

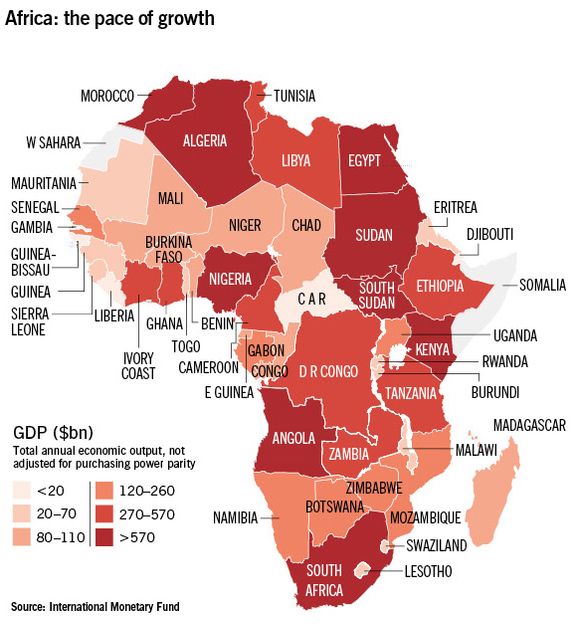

Africa is a continent on a spectacular scale. At 11.6m square miles, it is four times the size of Australia, three times that of Europe and more than twice the size of Latin America or India and China put together. A single African jungle, in the Congo, covers twice the area of western Europe and a single African desert, the Sahara, is the size of the US. Between the Sahara and the Cape of Good Hope there are 49 countries, a quarter of all the states on the planet.

In a crowded world, Africa’s wide-open spaces are the secret of its beauty. Imagine an African scene and you’ll almost certainly conjure up a landscape or animals, not a city or people. Size also explains Africa’s great attraction to foreigners. Outsiders have long been drawn to all that land, gold, rubber, slaves, diamonds and elephants. (This is partly what economists mean when they say that Africa is “cursed” by abundant resources). But Africa’s grand dimensions have also proved to be its best defence against acquisitive foreigners. Europeans and Americans spent much of the 19th century taming their own nations under great lattices of steel and copper, but the scale of Africa mostly defeated similar ambitions there. Even the insatiable Cecil Rhodes, the founder of Rhodesia, who dreamed of laying a railroad from Cape Town to Cairo, achieved only a fifth of that distance by his death in 1902, barely reaching Victoria Falls in 1904.

But if boundless space was key to Africa’s splendour and the guardian of its freedom, it also accounted for its lack of development, at least as westerners understood it. The rest of the world was originally colonised by African hunter-gatherers migrating out of the continent in search of fresh beasts. Around 9000 BC, as populations grew and humankind found it was hunting animals to extinction, people stopped moving and, by domesticating animals and sowing crops, invented farming. Farming produced 10 times more food from the same amount of land and in time these early settlements became towns and then cities.

This happened everywhere except Africa. The continent was just too big and its population too small for human beings to run out of space or animals. Two thousand years ago there may have been 40–50m Africans. Two hundred years ago, that number had barely changed. Why? Diseases like malaria and yellow fever, the vulnerability of farm animals to flies and disease, the resilience of man-eating predators and colonialism, which introduced Africans to more diseases and an industrial scale slavery that transported 25m Africans off the continent, are part of the reason. As a result, those great motors of progress—cities, communications and private property—emerged far later in Africa than in the rest of the world. Africans lived apart, enjoying an almost limitless freedom to roam and hunt. They never changed because they never had to. In time, to exist as a human being in Africa and in Europe or Asia came to denote two markedly different experiences.

When Europeans began arriving in Africa in the 15th century, they thought that they had discovered primitive man. But a survey of Africa’s ancient kingdoms suggests that it wasn’t that Europeans didn’t find civilisation in Africa, but that they hadn’t recognised it when they did. In the second millennium, there were around 200 African kingdoms and empires. Some were extremely durable, such as the Wolof Empire, which ruled Senegal and Gambia for six centuries, or the Kingdom of Kongo, which existed in Angola and southern Congo for five. Others seem to have been impressive explorers. Fourteenth-century coins minted in the Kilwa Sultanate on Africa’s east coast have been found on an Australian beach, while the discovery of traces of tobacco and cocaine, both of which originated in the Americas, in Egyptian mummies suggests some form of trans-Atlantic trade existed 3,000 years ago. Meanwhile the paved roads, national police forces and standing army of 200,000 of the Ashanti empire in Ghana—which saw off four British attempts at colonisation in the 19th century—bears comparison with Imperial Rome.

There were fundamental differences, though. Europe was a crowded place of small countries with finite borders and populations. In Africa, kingdoms and empires rarely met and their edges were not so much borders as markers of a gradual fading of influence. Private land ownership wasn’t necessary, and so didn’t exist. Citizenship was not a contract between the state and a set number of individuals, but a question of numerous overlapping loyalties to family, to village, and then to clan, region and empire, with culture, religion and language all commanding additional allegiances. For an African king, not knowing how many citizens there were made a political system based on individual rights unworkable. Far more practical was a system of collective rights, administered by the centre for the benefit of the whole, which remained a constant even if the numbers inside it varied.

This set of communal values is commonly known today by its southern African name, “ubuntu.” If European individualism was summed up in the 17th century by René Descartes’s “Cogito ergo sum,” “I think, therefore I am,” Africa’s communalist counter was, “I am because you are.” It is the idea that the individual is defined by membership of a community. Ubuntu’s stability can look attractive when compared with Europe’s turbulent history, but it has its faults, too. Africa’s long record of all-out tribal war shows what happens when one unified community meets another it doesn’t like. Equally, it is easy for ubuntu’s indifference to individual freedom to slide from benevolent dictatorship into tyranny.

Europeans tend to see African dictatorships as a hollowing-out of democracy. But in an African context, dictatorship is perhaps better understood as a perversion of ubuntu, what happens when a leader crosses the line between creating consensus and enforcing it through absolutism. Take another perennial concern of Europeans in Africa: corruption. To any right-thinking European, corruption is abhorrent. Viewed through the lens of ubuntu, the corruption and nepotism of a government minister can seem like a social obligation, the conscientious ubuntu African sharing his good fortune with his clan.

From the start, then, Africans and Europeans could look at the same object and see two different things. Today, as Africa changes rapidly, that has never been more true. When many outsiders think of Africa they still think of a starving baby. The truth is that the average African is a decently-clothed, increasingly prosperous adult. Last year, the average annual income for an African was $1,720, about $200 a year more than the average Indian’s, and for those still hanging on to the idea that Africa is primarily a destination for aid, the figures have long shown it to be more of a business destination. Foreign investment first overtook foreign aid to Africa a decade ago and last year hit $87.1bn, as opposed to $55.8bn in aid.

For more than a decade now, economic growth in Africa has been among the fastest on earth. That trajectory is widely expected to continue. Over the next decade and a half, hundreds of millions of Africans will pull themselves out of poverty, according to predictions from the World Bank and others, translating to a fall in the proportion of Africans defined as absolutely poor from more than half in 1990 to a quarter by 2030. By 2050, a typical African country like Zambia can reasonably expect to enjoy the same incomes as Poland does today, or possibly even South Korea.

This good news is studiously ignored by western aid agencies. While Africa’s economies have been taking off, aid agencies have managed to quadruple aid to Africa since the beginning of the 21st century by convincing the world that conditions there have never been worse. They have been able to do this because of their size and power. Aid today is a global industry that employs 600,000 people and turns over $134.8bn a year. That’s not charity any more but big business; the biggest, in fact, in Africa, where that turnover is equal to the annual GDP of Africa’s 20 poorest countries.

The business of aid is crisis. Using its mammoth resources and the unmatched institutional strength that comes from combining the UN, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, parts of the Pentagon, hundreds of foreign aid departments, thousands of foreign embassies and tens of thousands of foreign aid agencies, the aid industry has been able to define the story of Africa to the outside world according to its own priorities. At their conferences and workshops in Geneva and New York, aid workers note the new hope in Africa, measure it against their press releases about African need and conclude that reports about Africa’s rise are unhelpful. Aid workers used to say that their ultimate goal was to put themselves out of business. Today, the aid industry seems to have mislaid its earlier humility. Aid agencies often seem intent on ensuring that Africa’s story remains one of outsiders saving the children. Witness the lobbying by aid agencies of this year’s UN General Assembly, whose leaders are being asked to commit to ending poverty within 15 years. Every aid agency sees this brave mission as something to be achieved through aid. Not one mentions what the end of poverty actually implies: the end of aid.

You can see the same self-centred dynamic at work in accusations from western businesses and governments that China is acting like a modern-day imperialist in Africa. The idea that China is storming Africa is simply wrong. The biggest investor in Africa by holdings remains France, followed by the US, Britain, Malaysia, South Africa and then China. The notion that anybody could take over Africa betrays an enduring neo-colonial mindset. Africa has commodities that everybody wants, yes. These days, in a growing and ever more confident Africa, that draws suitors, not conquerors.

The same self-regard can be seen in western portrayals of African leaders as baby-eating dictators. Africa still has its dinosaurs, notably Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe and some of the steadily more authoritarian leadership of the African National Congress in South Africa. Across the continent, however, autocracy is down and democracy is up. As a region, the 49 countries of sub-Saharan Africa are now judged by the Freedom Index, produced by US organisation Freedom House, as more free than the Middle East, North Africa and Eurasia. Take Nigeria. For decades Nigeria was a prime example of a country cursed by resources. Cash from foreign oil companies propped up dictators and transformed politics into an endless, vicious power struggle. But this year, Nigeria held a democratic election in which the incumbent peacefully accepted defeat and was replaced by a rival promising reform. No one could reasonably argue that Nigerian politics are healthy, but since the end of military dictatorship in 1999, they have improved.

Or consider the case of Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda. Kenneth Roth, head of Human Rights Watch, regularly accuses Kagame of being a “tyrant,” a description which his organisation’s relentless campaigning has ensured is now accepted throughout the west. In response, Kagame has compared today’s western human rights campaigners to the European colonisers of previous centuries who told Africans what to do and how to behave because they knew better. And Kagame is surely correct that an accurate account of Rwanda since the 1994 genocide would focus not only on its human rights record, but also on its stunning transformation from an apocalyptic ruin into one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

That outsiders misperceived Africa was apparent when I first arrived on the continent in 2006. From afar, Africa had seemed to be about war, dictators, corruption and, yes, famine. On arrival, I found I was covering not implosion but economic explosion; not just hunger in Ethiopia but also yuppie food traders making their fortunes on Africa’s first commodity exchange; not savannahs and sunsets but Silicon Savannah, Nairobi’s exploding tech scene. The consensus among foreign correspondents was that Africa, like Asia before it, was increasingly a business story.

Yet our stories seemed to do little to change the outside world’s ideas of Africa. For a journalist, this was disconcerting. Merely gathering the facts, it seemed, was never going to be enough in Africa. The continent, with its thousands of mountains and rivers, its great forests and deserts, its great wide plains and its billion people, had become an abstraction. But if perceptions matter as much as facts, try this alternative perception of Africa on for size. It is developing fast. Development is not an even process, but one that always produces inequality on a scale that, if mishandled, can lead to resentment and conflict. Those who mistake the turbulence of the new Africa for the old story of endless war, however, should prepare themselves to be set straight, just as I was a few years ago in Somalia.

For as profound as Africa’s economic transformation is, the political implications of that growth are even more far-reaching. Money gives Africans the authority and the means to respond to anyone pushing them around, whether that’s the last of their autocrats, a new generation of jihadis, aid workers or anyone presuming to tell Africa’s story on its behalf. Half a century after Africans won their formal liberation, they are finally winning the substance of it. As Africa thrives, some old notions will die: that progress is something bestowed by the rich on the poor through assistance; that the west knows best. The developed world, of course, finds it hard to accept the way a fast-changing Africa upsets its ideas both of the continent and of itself. But in the end, the new continental narrative will prove irresistible. It is the story of how a billion Africans will finally win their freedom.

Alex Perry's "The Rift: A New Africa Breaks Free" is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson (£20)