“Look at these pictures carefully, and you will see what happened in Darfur.” On the back of a wrinkled drawing, encased in an acid-proof pocket, a child has left a handwritten message. Mohammed Ibrahim, a leader of the UK’s Masalit community, a persecuted group in Sudan, follows the instruction.

Smartly dressed in a chequered shirt and a navy jacket, Ibrahim is visiting the Wiener Holocaust Library in central London with several other members of the UK Darfur Diaspora Association. They are being shown the library’s first collection of primary sources that are unrelated to the Holocaust—a collection of children’s drawings from Darfur.

Some are blackly comic—a monkey scrambles up an apple tree and is shot by a compatriot in a tank, who operates a monkey-sized machine gun. But almost all of them depict violence. Straw-thatched houses on fire are juxtaposed by multicoloured patterns. Large pink and blue petals border a boy being dismembered by gunfire.

One captures Ibrahim’s attention. It’s a river scene. A woman in a yellow dress. A soldier on a horse. A row of barefoot men. One lies on the ground, a scribble of red spurting from his chest. The picture reminds him of an old friend.

Three thousand miles away, Abdulsalam Musa (not his real name) is working as a labourer in Sudan’s capital city, Khartoum, where the Blue Nile flows west from Ethiopia to meet the White Nile. He is 30 years old. He had hoped for a more skilled profession, but war had broken out six months earlier and cut his university studies short.

Abdulsalam’s father had been a carpenter in a village in Darfur, and as a child Abdulsalam would watch him working: tracing a pencil smoothly over timber and then cutting it. Even before he could write, Abdulsalam would copy his father’s patterns, tracing them into the earth.

He was only a child when they left the family home. His mother was pregnant, and his father had recently given her a new dress—yellow with embroidered flowers on the sleeves. She was wearing this when the Janjaweed came.

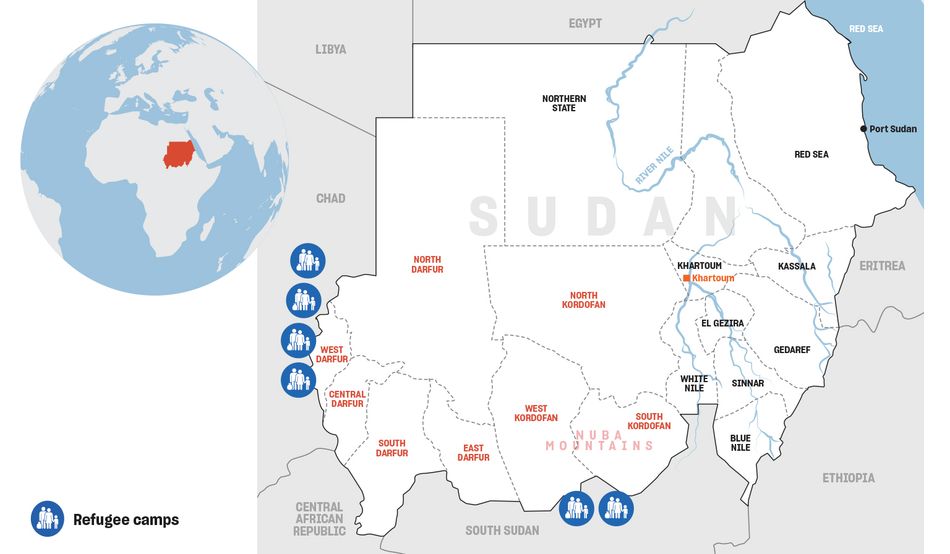

In 2003, violence broke out in Darfur, a region distinct in identity, hundreds of miles west of Khartoum; for decades, the only times the Sudanese government paid it much attention was during its occasional rebellions, which would quickly be quashed.

This time, two rebel factions targeted a number of military installations, claiming to be fighting against the region’s underdevelopment and political marginalisation. The government, then emerging from a gruelling civil war in the south of the country, decided against engaging directly with the rebel movement, and instead dispatched a largely Arab militia group known as the Janjaweed. Omar al-Bashir, who had been head of state since a coup in 1989, had long empowered regional militias to protect his regime from being overthrown.

Historically, Arab nomads had competed with Darfur’s sedentary populations over farmland and natural grazing grounds. These conflicts had been exacerbated by climate breakdown, drought and desertification. During the Cold War, millions of dollars’ worth of arms had been pumped into Sudan by both the United States and the Soviet Union, and the turf wars turned deadlier. The Janjaweed became more militarised.

In 2003, they stormed through the villages of Darfur in a genocidal campaign to wipe out non-Arab Sudanese inhabitants—targeting communities such as the Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit, from whom the rebels had emerged.

For Abdulsalam, the world unravelled in a day. The Janjaweed burned down his village, destroying livestock and spraying bullets at anything that moved. His father stayed back with the men to fight, but the women fled with the children. He had to run, barefoot, with his mother. A neighbour fled alongside them, preparing for death by murmuring the shahada, the declaration of faith. He remembers the roof of his home in flames.

At one point they were forced to hide inside a sidr bush, thick and thorny. If the Janjaweed discovered a young boy alive, they would kill him. Abdulsalam was concealed in the middle of the thorns, the warm, breathing bodies of his sisters wedged around him.

Another time, they took refuge with a group of people in a dried-up river bed. In the belly of that river, his mother gave birth to a girl.

As the children became desperately thirsty, the men who were with them left the riverbed to find water. This attracted the attention of the Janjaweed, who followed them back and discovered the hiding group.

Spotlight on Sudan

Janjaweed soldiers, on horseback and in pickup trucks, surrounded the rim of the river. The men were ordered to remove their shoes and line up in a row. One was shot in the chest; Abdulsalam watched the blood soaking the front of his jalabiya.

One of the civilian men had fled with a suitcase and a radio. He was caught and made to surrender his belongings. A looter—shafshafa, they were called—placed his gun on the ground so he could rifle through the suitcase.

With the soldiers distracted, Abdulsalam remembers his mother’s hand pushing him and his sisters to safety. His mother had his newborn sister on her back, an aunt took the second, and his grandmother took the third.

The family—along with hundreds of thousands of others—ended up in the heaving camps of neighbouring Chad. There, Abdulsalam became schoolmates with a boy called Mohammed Ibrahim, who had arrived around the same time. Their fathers had been friends before the war. Abdulsalam was a talented artist, his friend would later recall.

In 2007, a woman arrived in Chad seeking the testimonies of survivors from Darfur. Researcher Rosemary Monreau had listened to the stories of the Sudanese displaced in Cairo, and had enlisted a Darfuri interpreter and driver, lurching between refugee camps in a ramshackle jeep.

At the camps, the dust and the smells were overwhelming, Monreau remembers. Windstorms regularly hit the area, so many of the tents were ripped. She had started to collect victims’ statements when three displaced women stood up in a meeting and told her: “If you really want to know the truth, speak to the children.” So she did, asking for their strongest memories. Those whose Arabic was not so good asked to draw.

Some of the children depicted daily chores. Others drew the worst days of their lives

Some of the children depicted life before the war—daily chores, cooking, grinding sorghum grain into flour, carrying in the harvest; mothers braiding hair, prayers, family meals. Mohammed didn’t participate—“I was not a good drawer,” he tells me. But others, like Abdulsalam, drew the worst days of their lives.

Al-Bashir’s government in Khartoum had claimed that most of the casualties were combatants from Darfur’s rebel movements. But the children’s drawings of the survivors and the dead showed pregnant bellies and walking sticks, all rendered in coloured pencils.

Monreau felt a lump in her throat. The children could have been her grandchildren. She wasn’t sure she had the stomach for working in a war zone. “I had never looked for this work,” she told me. “It came looking for me.” Monreau would return to Sudan’s borderlands over the next few years, working in the camps under a pseudonym (both for her safety and for that of those giving testimonies), collecting hundreds more drawings from children like Abdulsalam.

Curiously, the pictures didn’t just show the Janjaweed. The children had drawn government helicopters and planes bombing villages, and soldiers from the government Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) fighting alongside the Janjaweed as both targeted civilians.

One of the most disturbing images shows a scene of rape, with a person averting their gaze. Another shows a man held at gunpoint with his head inserted into a plastic jerrycan. The SAF soldiers would then melt it on the victim’s head—a common method of torture in Darfur at the time.

Monreau brought the drawings back to the UK and offered them to the charity Waging Peace, for whom they were catalogued and interpreted by Bushra Rahama, founder of the Human Rights and Development Organization (Hudo), which monitors human rights in Sudan.

In 2014, Abdulsalam’s drawings ended up in a small collection that was sent on permanent loan to the Wiener Holocaust Library. In 2018, strikingly similar images drawn by children from Sudan’s Nuba mountains were added to the collection.

Then in spring 2019, a popular civilian uprising led to the removal of al-Bashir, who had been in power for 30 years. He was replaced by a Transitional Military Council (TMC), led by the head of the SAF, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. Burhan’s deputy was Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo, who headed the Rapid Support Forces (RSF)—formerly known as the Janjaweed.

That June, during the last nights of Ramadan and as people anticipated Eid, the SAF and the RSF together dispersed a sit-in of peaceful protesters with heavy gunfire. More than 100 were killed, and many others were “disappeared”. An estimated 40 bodies were thrown into the River Nile.

The violence of Darfur 16 years earlier, captured in the drawings of children, was being repeated. A young girl who witnessed the Khartoum massacre drew a picture; it was added to the collection, alongside Abdulsalam’s.

Mohammed and Abdulsalam’s paths had diverged in 2011. Abdulsalam got out of the camp, and went in search of education. He had a clear vision for the future, and there was no future inside the camp. Mohammed stayed, until in 2015 he heard that Chad—which was collaborating with the Sudanese government at the time—had captured six people at two other refugee camps and had handed them over to the Sudanese government as suspected rebels.

Those who had escaped the genocide in Darfur, especially those from the same tribes as the rebels, were under suspicion. Feeling at risk, Mohammed left the camp and spent 10 days crossing the desert to Libya in the back of a truck. He found Libya to be even more dangerous than the camp. There was civil war, and migrants faced arrest, unaffordable bail bonds and even torture.

When told of a place from which he could get to Europe, he begged to be taken there. He was given passage, despite not having enough money for the crossing. Later that year, he arrived in the UK seeking asylum.

In 2022, for the first time since he left, Mohammed visited his family for three months, and found the camp in an even worse condition than before. Food was scarce, drinking water was hard to access and malnutrition was rife.

The TMC was dissolved and replaced by a mixed civilian-military body, with a mandate to prepare the country for elections, in August 2019. As this council neared the end of its appointed term, the shift to civilian-led governance was expected to begin. But, in October 2021, the SAF and the RSF staged a coup, overthrowing the unity government and re-establishing a military dictatorship. By April 2023, the alliance between Burhan’s government forces and Hemedti’s RSF had soured, and war had broken out again.

“Now all of Sudan is Darfur,” a Sudanese refugee remarked at an event in the UK parliament in January, where the children’s drawings were displayed. Unlike Darfur, Khartoum had not seen warfare since British colonial rule a century earlier, and fighting between the two factions triggered a civilian exodus. More than 3.5m people have fled, and almost nine million are displaced within Sudan—more than in any other country. Among the internally displaced people, 97 per cent face severe hunger, and the SAF and RSF are accused of using “starvation tactics” against 25m civilians, half of Sudan’s population.

Mariam Suliman, a Darfuri who worked as a psychiatrist in the camp where Mohammed and Abdulsalam grew up, tells me that “other countries” are “making the scene more complicated”. She blames them for helping the war continue, for the sake of their own interests.

According to Sudanese officials and activists, the United Arab Emirates (UAE)is reportedly funding the RSF, smuggling arms and deploying drones in the country. The UAE has always denied the allegation. Despite casting itself as a mediator in the conflict, Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, is closely aligned with Egypt, which supports Burhan’s SAF.

For Saudi Arabia and the UAE, the war is a competition for regional hegemony. As a link between Africa and the Middle East, with 500 miles of Red Sea coastline, Sudan is strategically important.

Sudan is Africa’s third-largest producer of gold—but few Sudanese benefit

Though often framed as a “war of two generals”, a power struggle between Burhan and Hemedti—or a proxy war between the UAE and its competitors—the reality is more complicated, with a web of alliances and counter-alliances.

Arms flow into Sudan from countries including China, Iran, Egypt and Turkey. The UN Security Council’s arms embargo—poorly implemented and frequently violated—currently only applies to Darfur.

In February 2025, the SAF’s foreign minister struck a deal for Russia to establish a naval base on Sudan’s Red Sea coast. Meanwhile, the Wagner group, known in Sudan as “the Russian company”, also operates in the country, providing missile shipments to the RSF. As of last year, Ukrainian special forces were reportedly fighting against the RSF and Russian Wagner mercenaries in Khartoum.

Natural resources partly drive this interest. Sudan is Africa’s third-largest producer of gold, has substantial oil reserves and produces more gum arabic (used in soft drinks and chocolates) than any other country. But few Sudanese benefit. Sudan ranks 170th out of 191 nations in the UN Human Development Index, which measures life expectancy, living standards and education.

Gold is particularly important to the UAE. Overall, $115bn of gold was smuggled from Africa to the UAE between 2012 and 2022, according to the development group Swiss Aid. An estimated 50 to 80 per cent of Sudan’s mined gold is smuggled abroad, also mainly through the Emirates. Sudan’s largest industrial mine is owned by an Emirati company that reportedly has ties to the UAE royal family. While the UAE allegedly supports the RSF on the battlefield, the Emirati mine is in an area under government control, and so benefits the SAF.

Sudan’s military has increased gold production in such areas under its control, and has bombed RSF-controlled mines. The RSF also uses the profits from gold mining to fund its war, according to UN investigators. “Gold is destroying Sudan,” analyst Suliman Baldo told the New York Times in December, “and it’s destroying the Sudanese.”

Abdulsalam was in his second year of university when his studies were cut short by the war. These days, price increases in Port Sudan mean casual labour can no longer cover basic expenses, so he travels far outside Port Sudan to mine gold.

The work is backbreaking and dangerous. In some of the country’s mines, toxic chemicals like cyanide and mercury—both formally banned in 2019—are still used to separate metal from the rock. Last year, 14 workers were killed in north Sudan when a gold mine collapsed.

Mohammed Ibrahim now lives in Wales, near the sea. Two years ago, he co-founded the UK’s Darfur Diaspora Association, which includes genocide survivors from nine Darfuri ethnic communities. The aim of the organisation, he tells me, is to amplify the voices of people who are living in eastern Chad as refugees, and who have similar stories to himself and Abdulsalam.

“We are seeking justice,” he says, both for Darfuri survivors and for the internally displaced across Sudan. His organisation has built a relationship with the International Criminal Court (ICC) and works to coordinate testimonies, mediating between survivors and the court.

Experts report that the RSF is once again attacking communities in Darfur

In 2009 and 2010, the court issued two arrest warrants for Omar al-Bashir for crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide. He remains detained in Sudan under government custody. Al-Bashir has never been tried, and the ICC’s jurisdiction still only covers Darfur, despite mounting evidence of atrocities committed by the SAF and RSF in the country more widely.

Experts at Yale University’s Conflict Observatory report that the RSF is again attacking communities in Darfur. Mass graves have been discovered; neighbourhoods and villages razed. On 6th March, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) announced that Sudan had filed proceedings against the UAE, accusing it of being “complicit in the genocide on the Masalit” and other violations through its “extensive financial, political and military support” for the RSF.

Amid reports that UK Foreign Office officials put pressure on African diplomats to avoid criticising the UAE over its military support for the RSF, British Sudanese activists also want defence exports to the UAE, which is one of the UK’s largest arms buyers, curtailed until it can be ascertained that they are no longer arming the militia.

During her tenure as chief prosecutor for the ICC from 2012 until 2021, Fatou Bensouda expanded the types of evidence considered by the court. In 2007, during prosecutions of Sudanese officials, the Darfur children’s drawings, supplied by Waging Peace, were considered as secondary contextual evidence of atrocity crimes committed in Darfur. In effect, she said, they were harrowing eyewitness accounts.

“They are not mere illustrations,” Bensouda wrote in the foreword to a book compiled of the children’s drawings, “they are the voices of the voiceless, the cries of those who have endured unimaginable suffering and who deserve to finally see justice.”

Abdulsalam hasn’t drawn in two years. He had a sketchbook, but when the war began, it was left behind in his home in Omdurman, Sudan’s second city, just across the Nile from Khartoum.

The few recent artworks that he has kept are more peaceful: they show large houses crowded with furniture; a Volkswagen Passat against the mountains; a clear pond, framed by a single tree, a thicket of green in the background.

“This is what we are seeking,” he tells me over the phone, from an open field in Port Sudan, away from the ears of other people, the wind audibly buffeting around him. In Nubian-accented Arabic, he says that peace is a great blessing—one that people don’t truly value if they haven’t endured hardship.

Across Sudan, as new generations are caught up in a further cycle of violence, children are producing the same kind of images that he once drew. The value of peace is something he now understands.

Waging Peace is supporting Sudanese refugees in the UK. The book of drawings can be found at wagingpeace.info/the-book