Crossing the border between Northern Ireland and the south, it’s sometimes difficult to tell when you leave the kingdom and enter the Republic. The traffic signs are different and there are subtle clues too in the changing colour of road markings and even the texture of the asphalt. Your mobile phone will slip in and out of networks for several miles. The feeling is of one country fading indistinguishably into another. All around, there are signs of the activities that thrive in liminal places; petrol stations and shops taking advantage of the differences in tax and exchange rates, skid marks on the roads from jurisdiction-escaping joyriders, a hand-painted advertisement offering illegal “Red Diesel for Sale” discarded in a ditch.

Tied to a lamppost, near a defunct custom post, is a placard titled, “Respect the Remain Vote.” It continues, “Warning! If there is a hard border this road may be closed from March 2019.” It is signed, “Border Communities Against Brexit.” All along the 310-mile border between Northern Ireland and the Republic, such signs remind travellers and locals that the boundary will likely not remain invisible for long.

Ireland, north and south, is facing a border crisis. What is now a boundary between two European Union countries will soon be the Brexit frontline between the EU and the United Kingdom. When he visited the north in August, the new and decidedly worried Irish Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, took a stark tone when he addressed a crowd at Queen’s University in Belfast. He said that “every aspect of life,” in the north could be affected—“citizens’ rights, cross border workers, travel, trade, agriculture, energy, fisheries, aviation, EU funding, tourism, public services, the list goes on.” Arguing the onus was on the hard Brexiteers to explain how all of these things could be function tolerably around the hard border that we appear to be drifting towards, he nonetheless offered up a solution of his own, for a new bespoke EU/UK customs union that could apply after the UK had left the customs union proper. But he didn’t explain how this would work. The truth is that everyone is clutching at straws.

Both sides in the Brexit negotiations have noticed that the vanished border’s role in keeping the peace in Northern Ireland gives it a particular charge; all the more so because the power-sharing agreement in Stormont collapsed earlier this year and has struggled to recover. Michel Barnier, the European Commission’s Chief Negotiator for Brexit, has said that he wishes to avoid “a hard border, a new burden that is in contradiction with the Good Friday Agreement.” Varadkar made clear to the Belfast crowd that Ireland would expect no less, and would ensure it was high on the EU negotiators’ list of priorities. “We will do all we can,” he said, “in Brussels, in London and in Dublin.”

But Barnier can hardly ignore the border’s potential bearing on the wider negotiations, and in particular its use in countering Theresa May’s ominous assertion that “no deal is better than a bad deal.” He has rejected May’s proposal for a “frictionless border” and warns that “‘no deal’ is a return to a distant past,” a fair point in a region with a history of division and conflict memories of which stoke deep fears. There is real foreboding about Brexit splitting the island of Ireland with disastrous results. There is now the possibility that Dublin could delay discussions on any post-Brexit trade deal with the EU as a whole until the border question is settled, and that could suit Brussels if it helps to force concessions from the UK on other fronts.

The Common Travel Area, agreed following Ireland’s secession from the UK in 1922, allowed citizens to travel back and forth between north and south without passports long before the EU existed. This has led to some claims that there never really was a border. But there most definitely was—I grew up next to it, on the northern side. Built before the suburbs pushed out and enveloped the area, the housing estate my family lived in was situated in a hinterland. Bored teenagers would drive beaten-up cars in circles around fields until they gave out. The Orange Order would, and still do, march past the estate on the “Queen’s highway” every 12th July, commemorating the Battle of the Boyne. Occasionally, there would be a new arrival, an individual forced out of the city by paramilitaries for alleged crimes, usually drug-dealing; escaping punishment beatings, kneecappings or worse. On the other side of the border, in the sleepy Donegal villages of the Republic, paramilitaries themselves would live “on the run” from the north’s Royal Ulster Constabulary and Special Branch.

A stone’s throw from our house, almost at the end of our street, was the British army checkpoint with its cameras, listening devices, watchtower and armed soldiers. The back roads were obstructed by concrete blocks and barbed wire. The local pub and shop, the only ones for miles, were a long walk past that checkpoint. Every day brought the rumble of low-level anxiety that would often escalate, depending on the level of obstruction or hostility you faced, when giving your name, address and explaining why you were crossing the border. If you said your destination or origin was “Derry” rather than “Londonderry,” you could be hauled in to be searched and questioned. Having an Irish name was equally disadvantageous. Years later, I read Seamus Heaney’s version of such encounters in “The Ministry of Fear” section of his poem “Singing School” and recalled how often in my childhood my father, also called Seamus, was interrogated as my mother, sister and I waited by the roadside.

"A stone's throw from our house, almost at the end of our street, was the British army checkpoint"A mile beyond the army post was the customs hut, which was a more reserved affair, pulling in large vehicles. Trade and development were reflected in the quality of the roads and the relative scarcity of traffic—nowadays it’s omnipresent. When you crossed the pointedly-named “Liberty Bridge” into the Republic, you entered what is still colloquially referred to as “the Free State” and you could finally exhale.

If this kind of hard border were to return, the results would be bleak. The old checkpoints became the focus not just of dread and frustration but terrible violence. Houses in our neighbourhood were damaged when Republicans attempted to bomb the Culmore Road base. In 1990, five soldiers were killed at the nearby Coshquin border post when a civilian, Patsy Gillespie, was forced to drive a van containing 1,000lbs of explosives into the checkpoint by the Irish Republican Army, who were holding his family hostage. Gillespie’s death is memorialised in a plaque near the border. All along the boundary, during the Troubles, killings were carried out on all sides. No wonder the Police Federation for Northern Ireland has warned a hard border could become a propaganda tool and a target.

But what might the new Brexit hard border look like? Absent an immediate return to the conflict, it would not necessarily resemble the militarised frontier of my childhood. In the first instance, we are looking at a customs border. If the UK is outside the single market then all sorts of goods passing through might need to be checked for compliance with regulations and standards. And if it crashes out with “no deal,” then trade with the Republic (like the wider EU) would be governed by World Trade Organisation terms, which involve particular tariffs that officials would have to charge and collect. Checks will be slow, costly and focus on the thousands of large-goods vehicles. Traffic will worsen, and costly infrastructure will have to be built.

Smart technology, such as container tags and sensors and number-plate recognition could help, but these things are not the comprehensive solution some UK Conservatives are touting. As Simon Coveney, Ireland’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, recently told RTÉ: “What we do not want to pretend is that we can solve the problems of the border on the island of Ireland through technical solutions like cameras and pre-registration and so on. That is not going to work.” There are all sorts of ideas to smooth the “friction,” but the technology is still incomplete.

One proposal is to make customs units mobile, conducting searches and checks away from the actual border. This would avoid creating those physical manifestations of the border that have historically attracted attacks. Another idea, is the Trusted Trader scheme, under which legitimate companies register before crossing the border, which—hopefully—would help speed their passage. There may be something in it, but it only highlights an aspect to the border that is often overlooked: smuggling.

There is a long history of the practice in the borderlands. My maternal grandfather was a fisherman on Lough Foyle, which shadows the border. He trawled, swept for mines, recovered many victims of drowning and one night witnessed a lone Luftwaffe bomber, on its way to bomb Derry, flying low right above his boat. He was also a smuggler from Donegal to the city, via the US naval ships then anchored in the lough. He was shot at, lived under threat of arrest—and eventually ended up working for the customs office. The days of sea-smugglers or contraband crossing the land border inside prams, coffins and even a horse carcass may be long gone but smuggling is still there—even without any physical border. “Red diesel,” fuel intended for agricultural use which is taxed at a preferential rate, has been a thriving illegal industry. The tax gap between jurisdictions provides motorists in the border area with a cheap alternative, and cost the Northern exchequer over £50m in 2014. With a hard border, with different tariffs on either side, many more illegal opportunities would inevitably open up.

Continual disruption to border life is likely. Hospital treatments, especially in specialist and emergency cases, now span the boundary. So too does energy, tourism and the exchange of security information. Around 30,000 people cross the border each day for work, including students—and this gives rise to the question of whether Northern Ireland could be a back door to the UK for immigrants from the continent and beyond. The rights of EU citizens in the UK is still uncertain. Nationalists are deeply resistant to any idea of having to prove nationality or residency at the Irish border, but Unionists are equally opposed to the requirement to provide these things at airports and thus being distanced from the “mainland.”

"It can seem like London is doing all in its power to re-establish all the old divisions"Here we arrive at the deep and troubling psychological dimension of all this, which should not be underestimated. Any change to the character of the border awakens memories of the violence that scarred the country during the 19th and 20th centuries. For all their flaws, both the north and south are very different places today, partly as a consequence of being part of a larger cosmopolitan EU. Yet old loyalties linger and are stirred when condescending suggestions are made to treat Irish ports and airports as proxy British ones, or to encourage “Irexit,” as the right-wing think tank Policy Exchange recently has.

Calls to avoid a hard border are almost universal yet there is a sense that Brexit is causing an inexorable and self-destructive slide towards it. The economies of Northern Ireland and the Republic are now deeply intertwined and dependent on one another, as the local population is well aware. Every border constituency voted “Remain.” The electorate of Foyle, where I grew up in, voted 78.3 per cent against Brexit; the third highest result in the UK.

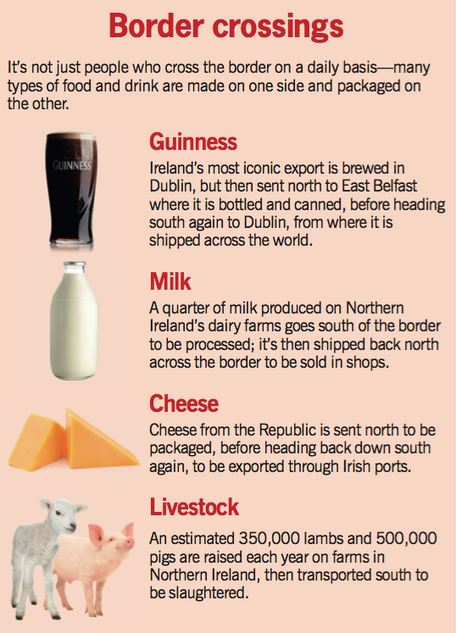

Livelihoods depend on the fluidity between the two states. Cross-border trade is estimated at £43bn a year with 400,000 connected jobs. Pharmaceuticals, alcohol, livestock and many other industries are dependent on that mutually-beneficial relationship. A sobering prediction comes from Ireland’s Economic and Social Research Institute. Depending on the terms of Brexit, UK/Ireland trade could decline by as much as 20 per cent, with the loss of as many as 40,000 jobs and a decline in Irish GDP of as much as 3.5 per cent or €9bn. “Nobody in Ireland,” warns the British Irish Chamber of Commerce, “would be unaffected.” Relying on the Republic for over a third of its exports, Northern Ireland would be similarly strained. Given that agriculture would be particularly affected, the pro-Brexit position of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), traditionally a bastion of the Protestant rural vote and now part of Theresa May’s Westminster coalition, could prove myopic. While the Ulster Farmers Union welcomed the DUP’s insistence on agricultural support as part of their deal with the Tories, it is uncertain whether this will compensate for the loss of EU grants.

The imperfect but continuing success of the Peace Process has been partly down to the disappearance of the border. Northern Irish citizens are entitled to dual nationality while the added sense of European identity has diluted the old “us and them” mindset. The dismantling of border security installations allowed Nationalists to imagine that it had gone for good. Similarly, pragmatism outdid ideology on the unionist side, as exemplified by the spectacle of Ian Paisley Jnr advising his constituents to claim an Irish passport and keep their freedom of movement while simultaneously campaigning to vote “Leave.”

The large “Remain” vote crossed many traditional religious and political divides. It also pointed the way to generational change, with impassioned younger voters arguing for their European identity and rights. Yet it can seem like London is doing all in its power to re-establish the old divisions. The Conservative deal with the DUP further undermines the already-paralysed Northern Ireland Assembly. John Major, who did much to set the region on the path towards peace when prime minister, told the BBC that peace can’t be seen “as a given. It’s not certain. It’s under stress. It’s fragile.” In Major’s eyes, the abandonment of impartiality by the British government poses a threat to hard-earned stability. But Major was dismissed by Brexiters—Iain Duncan Smith labelled him “strangely bitter.”

The failure of the Irish border to register on the British debate during the referendum campaign is indicative of deep complacency towards the region. Time and again, concerns have been passed over. A joint press conference by Major and Tony Blair in June last year was overshadowed by gossip about David Cameron’s immigration target. Theresa Villiers, the then-Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, came out as an enthusiastic Brexit supporter, despite warnings of what it could mean for the north. The sad truth is that for many in mainland Britain, Northern Ireland has always been a side issue. And this has led to suspicion in Northern Ireland that “British” really means “English”—that the UK’s partnership of equals is no such thing.

The fact of a 56 per cent Remain vote in the north further fuels that sense of grievance. With the deaths of Ian Paisley Snr and Martin McGuinness, there’s an added unsteadiness in the DUP and Sinn Féin. Both have reacted by digging in, and the population has followed suit—neither party has ever been so popular. For all the talk of cultural buzz and investment, the peace walls and segregated schools remain. To make progress on truly integrating Northern Irish society requires more than a sleepwalking current peace; it will require a dismantling of the bastions of traditional sectarian power, beginning with the grip the various churches and historical institutions have on so much of life. That seems a distant prospect. And now, the annual testing of the peace with the marching and bonfire season could soon be joined by the continual presence of a reanimated border.

Peace is not just the absence of threat: it is also the absence of obstruction. For all the hopes raised by the fact that young people in Northern Ireland are shedding sectarianism, those divides still benefit those in power. This has encouraged the export of the one thing that Northern Ireland can ill afford to lose: its youth. There is much to hope for. The region is no longer the place it once was. The centre of Belfast at night is far from the ghost town I encountered when first living there. While Northern Ireland still has the capacity to exasperate and bewilder, from the flag furore to the cognitive dissonance of graffiti exclaiming “Fuck off back to Ireland,” life is generally more diverse than before. Though resisted by ideologues on all sides, there is a silent grudging acceptance that the place is different and that we are regarded as distinctly “other” by the rest of Ireland and the UK.

Perhaps the most helpful outcome of Brexit negotiations would be to accept its unique status as a country in itself, albeit one intrinsically reliant on two other states. Sadly, this seems unlikely. A measure proposed at the European Parliament by Sinn Féin to recognise this formation was defeated by 374 votes to 66. It would have seen Northern Ireland remain both within the EU and the UK, retaining both access to the single market and freedom of movement. The proposal was opposed by unionists, who saw it as undermining British sovereignty.

Sinn Féin is now calling for a border poll on the reunification of Ireland. That may seem unrealistic, but recall the unlikely outcome of the Brexit vote. And keep in mind those younger Northern Irish voters who feel their future in Europe has been taken from them, primarily by older voters across the Irish Sea. It’s worth remembering, too, how contingent the border has always been. When first dreamt into being, it could’ve been as far south as Lough Sheelin in South Cavan, or as far north as the River Bann. Its eventual location was settled by the arbitrary balance of brute political and physical force.

It was, then, invented once and it may be reimagined again, with who knows what consequence. This time the reimagining will be provoked by a political project that most people on the island of Ireland do not want and for which they did not vote.