Read more: A real industrial revolution

Update, 23/01/17: Governments of all colours try to boost the performance of the economy using “horizontal” measures operating across the whole economy—reforming taxes or raising educational standards. But when it comes to serious Industrial Strategy, governments have to focus on “vertical” measures that get down into the substance of particular places and technologies. That is what the UK government's new Industrial Strategy Green Paper does—so it passes the crucial test of being serious and credible. It is not just about skills in general but the creation of new institutes of technology with a focus on particular STEM skills. It is not just about boosting the performance of British industry as a whole; it gets into identifying key sectors and technologies which can gain the most from shrewd government policies. Whitehall is wary of such granular decision making but without it, those tasked with implementing policy are like generals who will only fight an air war and never gain any ground as a result. My essay for Prospect gave some examples of what these actual decisions might be. They are hard to get right and it is good that the government is genuinely consulting and listening. That should lead up to more specific substantive decisions for the Autumn Statement. But we have a first map and it is taking us in the right direction.

The Brexit majority comprised an alliance of two groups. First, there were those who felt they had lost out from globalisation and blamed migration for stagnant wages. Then there were the older generation enjoying greater financial security, for whom the performance of the economy just did not matter. It was an alliance of the excluded and the insulated.

I personally believe it would have been far better if we had voted to stay in the European Union, and—with what happens next still far from clear—hope that the coming negotiations produce a result that leaves us positively engaged with Europe. But, just possibly, we can use the shock of the aftermath of the Brexit vote to tackle the deep problems that it revealed.

The troubling truth, revealed by the Brexit vote is that even when the British economy did grow, and even where productivity did improve, very little of that benefit has been feeding through into median wages—many people have simply ceased to gain from growth. Instead, it was all being captured by the most affluent who often also tend to be older. In particular, economic gains were captured by pensioners as extra resources were put into plugging deficits in pension schemes from which young people were excluded.

More recently, this problem has been exacerbated by our terrible productivity performance—making it much harder to boost living standards for anyone. Britain, then, has a pressing need to get better at generating more wealth and better too at giving more people a stake in it, especially the younger generation. Both halves of that are ambitious, and Theresa May’s “One Nation” agenda promises to do something about both. But how? The formidable challenges here are easier to define than to answer. The prime minister has suggested that a bold “industrial strategy” can help her deliver, which is a good place to start, but what exactly is it?

For a generation, the theory that Whitehall purported to follow towards industry could be traced back to Nigel Lawson’s seminal Mais lecture of 1984, delivered almost exactly a year after his appointment as Chancellor of the Exchequer under Margaret Thatcher. He was very conscious of the need to respond to the economic failures of the UK’s recent past. He argued that over the course of the 1960s and 70s, detailed micro-economic interventions in labour and other markets, with price and income policies being the obvious example, had been used to control inflation; meanwhile the big macro-economic tools of fiscal and monetary policy were used to stimulate growth. This allocation of instruments needed to be reversed. Macro-policy should now be devoted to controlling inflation, which could free micro-policy to raise the growth rate. But how could it effectively do so?

The American economist Mancur Olson had, after all, argued in The Logic of Collective Action (1965) that the efforts to raise the growth rates in mature economies often failed, because democracies were colonised by organised interest groups that strengthened market incumbents at the expense of insurgents. Traditional industrial policy was a classic example of the problem: backing winners had become bailing out losers. Thatcher, Lawson and their successors responded to this critique by downplaying interventions in particular firms and sectors, and instead emphasised reforms that were designed to improve efficiency across the economy—by pushing for more flexible labour, financial and above all product markets. They were scraping the barnacles off the ship of state. Industrial policy, then, came to mean getting rid of barriers and enabling the economy as a whole to function better.

After the financial crisis of 2007-08, and the long slump in productivity growth that has followed, the question of industrial policy is once more on the agenda. Can governments boost the performance at least of particular sectors, if not particular businesses? Or would that take us back to the bad old days of keeping “lame ducks” afloat?

Whatever the theory and whatever the claim, every government has always found itself drawn into “vertical” involvement in particular sectors, as opposed to restricting itself to “horizontal” reforms that apply to the economy as a whole.

Even in Thatcher’s heyday the government was promoting new industries. The yuppies of the 1980s were mocked for their brick-sized mobile phones, but actually mobile telecommunications is a vivid example of using industrial strategy to promote insurgents—made possible by the privatisation of BT and the lack of any government interest in protecting landline telephony, something which has hampered progress in France (see “The French Disconnection,” in Prospect’s April issue). The rise of Vodafone to become, for a time, one of Europe’s biggest companies would not have been possible without Britain’s role in the European single market and a deliberate effort by the government to shape European and global mobile standards in a way that favoured that company. There are important lessons here for Liam Fox’s new trade ministry, because most trade negotiation is about regulatory standards, not tariffs. In the 1980s, the UK fought and won a battle to get the right standards to promote the British players in the industry.

We later messed up in telecoms because the auction of 3G licenses was so ingeniously designed so to extract maximum revenue for the Treasury, that it took too much, weakening the industry. Our performance on 4G has been middling. Now we should aim at regaining our European lead through the early adoption of 5G which could get us a strong position in the “internet of things”: the networking of various devices, sensors and vehicles which many technologists see as the next frontier of the communications revolution. Forging a strategic partnership with China’s Huawei might just get us there; passivity won’t cut it.

The old system imposed a divide between brokers and market-makers and this enabled Britain’s finance houses to operate with low levels of capital, although with the result that London did not promote big financial players. The new system brought bigger firms into the City. It was a classic example of policy developed to boost the performance of a specific industry.

For 20 years the government, and especially the Treasury, whilst wary of intervention in virtually every other sector, doggedly promoted financial services as a key British industry. That included the eastward extension of the London Underground to allow the expansion of the City into the former docklands area of Canary Wharf—I doubt there would have been similar support for building a new line to a new manufacturing centre. Today’s equivalent might be to give priority to the Oxford-Cambridge rail link and connect that important cluster of knowledge-based industries.

The fundamental idea behind a modern, pro-active industrial strategy is that government can be a bearer of risk. The nation state is the biggest risk pool we have got and should support inherently risky and uncertain activities.

Risk also explains why industrial “clusters” work—they are low risk environments for high risk activities. You can lose your job but with a better chance of moving on to another one which uses your expertise without uprooting your family. The decision by the California Supreme Court to strike down “non-compete” clauses in employment contracts, which barred one firm’s staff from moving to work for a rival, was a crucial moment in the rise of Silicon Valley.

We beat ourselves up in Britain for lacking the entrepreneurial appetite for risk. But that is a misreading. Actually government has tended to withdraw public support far too soon for new technologies, and then criticised the private sector for failing to shoulder greater risks than—say—firms would be expected to bear in the United States.

In the US, entrepreneurs are much more likely to win speculative government contracts. Public funding for science and technology went much closer to market in the US than in Britain before the creation of the Technology Strategy Board, now Innovate UK, was established to plug that gap. Thomas Jefferson might have had a vision for an America of sturdy individuals, but Alexander Hamilton, another of the founding fathers of the US, believed in harnessing the power of government to promote business: modern America is a Hamiltonian state hidden behind Jeffersonian rhetoric. The most ambitious advocates of industrial strategy in the UK, such as Mariana Mazzucato (who writes overleaf), are often only urging us to do what American Republicans do when they are in government.

But in opposition, George Osborne and I had commissioned James Dyson to advise us on what could be done to promote innovation and he had proposed a network of new research and development (R&D) centres co-funded by the public and private sectors. At the same time, Herman Hauser, an entrepreneur based in the “Silicon Fen” cluster of high-tech businesses around Cambridge, had recommended something very similar in an official report to Mandelson.

One of the big weaknesses identified in both these reports was that Britain did not have a strong network of institutions straddling the gap between research and business. The Coalition thus created a network of “catapult” centres, to propel big technological ideas forward using a mix of public and private funds. It was a great example of how government could take some risk and attract private investment, rather than crowd it out.

An early decision helped educate my thinking here. A Space Leadership Council had been created by my Labour predecessor Paul Drayson and one of its first meetings was scheduled shortly after I arrived in BIS. Should I go along, or cancel it and review the whole idea? I went along and was impressed by what could be done when government brought science and tech, business and academia together.

We ended up pursuing a similar approach in many other sectors.

The first step was often commissioning a road map which tried to set out, despite all the obvious uncertainties, where a technology was heading, where the commercial players are doing their R&D and where they might do more if we could plug the gaps in publicly-funded research.

We developed competitions for new R&D facilities on university sites, with the rewards requiring matching commercial funds. At times we discovered that government regulations have been written with an outmoded assumption about how a technology works, inhibiting innovation—that happened, for example, in the way that the EU registered new drugs in batches, making it harder for us to promote innovative pharmaceutical manufacturing in the UK using new continuous processes.

In some fields, the most obvious contribution for government to make might be providing a regulated space for experiment—a safe area for developing robots and driverless vehicles for example. In other contexts, you might find that government is holding an industry back by being a fragmented and cautious purchaser. Then there are missed opportunities to promote the right standards—standards for photovoltaic cells for example are set by their performance in direct sunlight biasing them against innovative technologies designed for Britain’s more diffuse light.

I tried (but failed) to get different government bodies to respond to the reality that we were all buying Earth observation data from other people’s satellites, by promoting a British Earth observation capacity which, in partnership with the private sector, could have promoted innovation and saved money.

You cannot do all this by indiscriminate, economy-wide provision of tax reliefs and deregulation, however desirable. You have to understand what is happening sector by sector and then design your policies accordingly. But government has limited capacity and in many cases the best policy is just to leave well alone. So the crucial decision then becomes what to focus on.

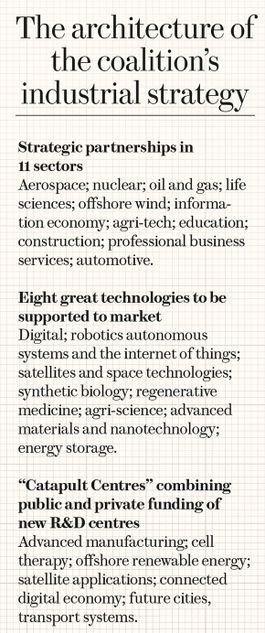

The Coalition ended up with four different approaches. It sounds a bit of a muddle but it actually worked by giving us some flexibility. Cable focused on sectors where there was a useful government role. He is quite a petrol head, keen on automotive and aerospace. He also had real expertise in the energy sector. I focused on key technologies and fields such as agriculture, life sciences and education. Osborne was increasingly interested in place, notably though not exclusively the North and Manchester. No 10 promoted Tech City and was also keen on setting big challenges and prizes for tackling them—anti-microbial resistance, for example. By 2013 this had all come together in an industrial strategy, summarised in the box above.

There are objections to all this. Sometimes the cautious advice was against doing things because we were taking risky decisions on limited information in an uncertain world. But it is like those thermometers on church towers showing how appeals for funds are going. It might be safest to come in with the final donation which reaches the target, but sometimes it is the job of government to put down the first funds to get the appeal going and show what it is prepared to back.

Then there is the argument that new technologies are only a small part of the economy. But, of course, well beyond high tech itself, are many unglamorous sectors which can be transformed by technological change—warehousing or retailing, for example. And the good news—set out in Enrico Moretti’s New Geography of Jobs—is that in the high-skilled clusters less-skilled jobs command higher earnings too. If the best way to get a well-paid job is to get a degree, the next best way is to work where lots of other people have one. This really does help spread prosperity.

Thirdly there is the objection that you end up backing incumbents not insurgents. There is nothing wrong of course with being a big successful company—and Britain could do with a few more “primes” like GlaxoSmithKline or Rolls Royce. But new technologies are inherently disruptive and are probably the biggest challenge a big company faces.

So the objections are legion, but they have to be seen off. I suggest that there are 10 tests, set out in the box below, which ministers can use to develop a practical industrial policy.

Some of my tests will seem entirely obvious, and in a way they are—they certainly reflect what I saw other countries doing. Why, for example, did the US shift its position and become keen on extending the life of the International Space Station? Because that would ensure more contracts for Space X to supply it, and help the company to achieve commercial viability.

But it is also surprisingly difficult to apply these tests in British government. Some departments are institutionally blind to innovation: the Department for Energy and Climate Change, for example, was full of economists designing markets but shockingly weak on understanding technologies. They failed to spot that their smart meter programme was going to be an expensive missed opportunity. UK Trade & Investment, the small department dedicated to promoting trade, was the custodian of much relevant expertise, but it has just been re-organised unnecessarily with a loss of focus. Likewise, some of the infrastructure of leadership councils and technical advice which Vince and I built up was abandoned in the year after the Conservative win in 2015—though it is not too late to revive that.

Even though instinctively Osborne got a lot of this, his Treasury was equally instinctively wary of Innovate UK, the body which actually delivers on a lot of the items on my 10-point list. It ended up getting hefty budget cuts in 2015 with a very difficult shift of funding for start-ups into loans.

Now there is a fantastic opportunity to make all this work. May understands the power of government. She is not a pessimist who thinks government is always the problem and never part of the solution. With the easing of the fiscal rules and the return of Greg Clark to the business department there is a real opportunity.

We don’t need to waste two years going back to the beginning and re-learning old lessons. The Brexiters always insisted they wanted an open trading innovative economy. Leaving Europe may not help with that, but here is an agenda that can.

Ind 101: a crash course in Industrial Strategy

10 tests the new Business Secretary Greg Clark should apply

Update, 23/01/17: Governments of all colours try to boost the performance of the economy using “horizontal” measures operating across the whole economy—reforming taxes or raising educational standards. But when it comes to serious Industrial Strategy, governments have to focus on “vertical” measures that get down into the substance of particular places and technologies. That is what the UK government's new Industrial Strategy Green Paper does—so it passes the crucial test of being serious and credible. It is not just about skills in general but the creation of new institutes of technology with a focus on particular STEM skills. It is not just about boosting the performance of British industry as a whole; it gets into identifying key sectors and technologies which can gain the most from shrewd government policies. Whitehall is wary of such granular decision making but without it, those tasked with implementing policy are like generals who will only fight an air war and never gain any ground as a result. My essay for Prospect gave some examples of what these actual decisions might be. They are hard to get right and it is good that the government is genuinely consulting and listening. That should lead up to more specific substantive decisions for the Autumn Statement. But we have a first map and it is taking us in the right direction.

The Brexit majority comprised an alliance of two groups. First, there were those who felt they had lost out from globalisation and blamed migration for stagnant wages. Then there were the older generation enjoying greater financial security, for whom the performance of the economy just did not matter. It was an alliance of the excluded and the insulated.

I personally believe it would have been far better if we had voted to stay in the European Union, and—with what happens next still far from clear—hope that the coming negotiations produce a result that leaves us positively engaged with Europe. But, just possibly, we can use the shock of the aftermath of the Brexit vote to tackle the deep problems that it revealed.

The troubling truth, revealed by the Brexit vote is that even when the British economy did grow, and even where productivity did improve, very little of that benefit has been feeding through into median wages—many people have simply ceased to gain from growth. Instead, it was all being captured by the most affluent who often also tend to be older. In particular, economic gains were captured by pensioners as extra resources were put into plugging deficits in pension schemes from which young people were excluded.

More recently, this problem has been exacerbated by our terrible productivity performance—making it much harder to boost living standards for anyone. Britain, then, has a pressing need to get better at generating more wealth and better too at giving more people a stake in it, especially the younger generation. Both halves of that are ambitious, and Theresa May’s “One Nation” agenda promises to do something about both. But how? The formidable challenges here are easier to define than to answer. The prime minister has suggested that a bold “industrial strategy” can help her deliver, which is a good place to start, but what exactly is it?

For a generation, the theory that Whitehall purported to follow towards industry could be traced back to Nigel Lawson’s seminal Mais lecture of 1984, delivered almost exactly a year after his appointment as Chancellor of the Exchequer under Margaret Thatcher. He was very conscious of the need to respond to the economic failures of the UK’s recent past. He argued that over the course of the 1960s and 70s, detailed micro-economic interventions in labour and other markets, with price and income policies being the obvious example, had been used to control inflation; meanwhile the big macro-economic tools of fiscal and monetary policy were used to stimulate growth. This allocation of instruments needed to be reversed. Macro-policy should now be devoted to controlling inflation, which could free micro-policy to raise the growth rate. But how could it effectively do so?

The American economist Mancur Olson had, after all, argued in The Logic of Collective Action (1965) that the efforts to raise the growth rates in mature economies often failed, because democracies were colonised by organised interest groups that strengthened market incumbents at the expense of insurgents. Traditional industrial policy was a classic example of the problem: backing winners had become bailing out losers. Thatcher, Lawson and their successors responded to this critique by downplaying interventions in particular firms and sectors, and instead emphasised reforms that were designed to improve efficiency across the economy—by pushing for more flexible labour, financial and above all product markets. They were scraping the barnacles off the ship of state. Industrial policy, then, came to mean getting rid of barriers and enabling the economy as a whole to function better.

After the financial crisis of 2007-08, and the long slump in productivity growth that has followed, the question of industrial policy is once more on the agenda. Can governments boost the performance at least of particular sectors, if not particular businesses? Or would that take us back to the bad old days of keeping “lame ducks” afloat?

Whatever the theory and whatever the claim, every government has always found itself drawn into “vertical” involvement in particular sectors, as opposed to restricting itself to “horizontal” reforms that apply to the economy as a whole.

Even in Thatcher’s heyday the government was promoting new industries. The yuppies of the 1980s were mocked for their brick-sized mobile phones, but actually mobile telecommunications is a vivid example of using industrial strategy to promote insurgents—made possible by the privatisation of BT and the lack of any government interest in protecting landline telephony, something which has hampered progress in France (see “The French Disconnection,” in Prospect’s April issue). The rise of Vodafone to become, for a time, one of Europe’s biggest companies would not have been possible without Britain’s role in the European single market and a deliberate effort by the government to shape European and global mobile standards in a way that favoured that company. There are important lessons here for Liam Fox’s new trade ministry, because most trade negotiation is about regulatory standards, not tariffs. In the 1980s, the UK fought and won a battle to get the right standards to promote the British players in the industry.

We later messed up in telecoms because the auction of 3G licenses was so ingeniously designed so to extract maximum revenue for the Treasury, that it took too much, weakening the industry. Our performance on 4G has been middling. Now we should aim at regaining our European lead through the early adoption of 5G which could get us a strong position in the “internet of things”: the networking of various devices, sensors and vehicles which many technologists see as the next frontier of the communications revolution. Forging a strategic partnership with China’s Huawei might just get us there; passivity won’t cut it.

"The yuppies of the 1980s were mocked for their brick-sized mobile phones, but mobile telecoms is a vivid example of using industrial strategy to promote insurgents"Financial services was another example of the unspoken 1980s industrial strategy. Crucial to this was the Big Bang, the wave of financial deregulation that removed barriers to entry into the British financial services sector.

The old system imposed a divide between brokers and market-makers and this enabled Britain’s finance houses to operate with low levels of capital, although with the result that London did not promote big financial players. The new system brought bigger firms into the City. It was a classic example of policy developed to boost the performance of a specific industry.

For 20 years the government, and especially the Treasury, whilst wary of intervention in virtually every other sector, doggedly promoted financial services as a key British industry. That included the eastward extension of the London Underground to allow the expansion of the City into the former docklands area of Canary Wharf—I doubt there would have been similar support for building a new line to a new manufacturing centre. Today’s equivalent might be to give priority to the Oxford-Cambridge rail link and connect that important cluster of knowledge-based industries.

The fundamental idea behind a modern, pro-active industrial strategy is that government can be a bearer of risk. The nation state is the biggest risk pool we have got and should support inherently risky and uncertain activities.

Risk also explains why industrial “clusters” work—they are low risk environments for high risk activities. You can lose your job but with a better chance of moving on to another one which uses your expertise without uprooting your family. The decision by the California Supreme Court to strike down “non-compete” clauses in employment contracts, which barred one firm’s staff from moving to work for a rival, was a crucial moment in the rise of Silicon Valley.

We beat ourselves up in Britain for lacking the entrepreneurial appetite for risk. But that is a misreading. Actually government has tended to withdraw public support far too soon for new technologies, and then criticised the private sector for failing to shoulder greater risks than—say—firms would be expected to bear in the United States.

In the US, entrepreneurs are much more likely to win speculative government contracts. Public funding for science and technology went much closer to market in the US than in Britain before the creation of the Technology Strategy Board, now Innovate UK, was established to plug that gap. Thomas Jefferson might have had a vision for an America of sturdy individuals, but Alexander Hamilton, another of the founding fathers of the US, believed in harnessing the power of government to promote business: modern America is a Hamiltonian state hidden behind Jeffersonian rhetoric. The most ambitious advocates of industrial strategy in the UK, such as Mariana Mazzucato (who writes overleaf), are often only urging us to do what American Republicans do when they are in government.

But in opposition, George Osborne and I had commissioned James Dyson to advise us on what could be done to promote innovation and he had proposed a network of new research and development (R&D) centres co-funded by the public and private sectors. At the same time, Herman Hauser, an entrepreneur based in the “Silicon Fen” cluster of high-tech businesses around Cambridge, had recommended something very similar in an official report to Mandelson.

One of the big weaknesses identified in both these reports was that Britain did not have a strong network of institutions straddling the gap between research and business. The Coalition thus created a network of “catapult” centres, to propel big technological ideas forward using a mix of public and private funds. It was a great example of how government could take some risk and attract private investment, rather than crowd it out.

An early decision helped educate my thinking here. A Space Leadership Council had been created by my Labour predecessor Paul Drayson and one of its first meetings was scheduled shortly after I arrived in BIS. Should I go along, or cancel it and review the whole idea? I went along and was impressed by what could be done when government brought science and tech, business and academia together.

We ended up pursuing a similar approach in many other sectors.

The first step was often commissioning a road map which tried to set out, despite all the obvious uncertainties, where a technology was heading, where the commercial players are doing their R&D and where they might do more if we could plug the gaps in publicly-funded research.

We developed competitions for new R&D facilities on university sites, with the rewards requiring matching commercial funds. At times we discovered that government regulations have been written with an outmoded assumption about how a technology works, inhibiting innovation—that happened, for example, in the way that the EU registered new drugs in batches, making it harder for us to promote innovative pharmaceutical manufacturing in the UK using new continuous processes.

In some fields, the most obvious contribution for government to make might be providing a regulated space for experiment—a safe area for developing robots and driverless vehicles for example. In other contexts, you might find that government is holding an industry back by being a fragmented and cautious purchaser. Then there are missed opportunities to promote the right standards—standards for photovoltaic cells for example are set by their performance in direct sunlight biasing them against innovative technologies designed for Britain’s more diffuse light.

I tried (but failed) to get different government bodies to respond to the reality that we were all buying Earth observation data from other people’s satellites, by promoting a British Earth observation capacity which, in partnership with the private sector, could have promoted innovation and saved money.

You cannot do all this by indiscriminate, economy-wide provision of tax reliefs and deregulation, however desirable. You have to understand what is happening sector by sector and then design your policies accordingly. But government has limited capacity and in many cases the best policy is just to leave well alone. So the crucial decision then becomes what to focus on.

The Coalition ended up with four different approaches. It sounds a bit of a muddle but it actually worked by giving us some flexibility. Cable focused on sectors where there was a useful government role. He is quite a petrol head, keen on automotive and aerospace. He also had real expertise in the energy sector. I focused on key technologies and fields such as agriculture, life sciences and education. Osborne was increasingly interested in place, notably though not exclusively the North and Manchester. No 10 promoted Tech City and was also keen on setting big challenges and prizes for tackling them—anti-microbial resistance, for example. By 2013 this had all come together in an industrial strategy, summarised in the box above.

There are objections to all this. Sometimes the cautious advice was against doing things because we were taking risky decisions on limited information in an uncertain world. But it is like those thermometers on church towers showing how appeals for funds are going. It might be safest to come in with the final donation which reaches the target, but sometimes it is the job of government to put down the first funds to get the appeal going and show what it is prepared to back.

Then there is the argument that new technologies are only a small part of the economy. But, of course, well beyond high tech itself, are many unglamorous sectors which can be transformed by technological change—warehousing or retailing, for example. And the good news—set out in Enrico Moretti’s New Geography of Jobs—is that in the high-skilled clusters less-skilled jobs command higher earnings too. If the best way to get a well-paid job is to get a degree, the next best way is to work where lots of other people have one. This really does help spread prosperity.

Thirdly there is the objection that you end up backing incumbents not insurgents. There is nothing wrong of course with being a big successful company—and Britain could do with a few more “primes” like GlaxoSmithKline or Rolls Royce. But new technologies are inherently disruptive and are probably the biggest challenge a big company faces.

So the objections are legion, but they have to be seen off. I suggest that there are 10 tests, set out in the box below, which ministers can use to develop a practical industrial policy.

Some of my tests will seem entirely obvious, and in a way they are—they certainly reflect what I saw other countries doing. Why, for example, did the US shift its position and become keen on extending the life of the International Space Station? Because that would ensure more contracts for Space X to supply it, and help the company to achieve commercial viability.

But it is also surprisingly difficult to apply these tests in British government. Some departments are institutionally blind to innovation: the Department for Energy and Climate Change, for example, was full of economists designing markets but shockingly weak on understanding technologies. They failed to spot that their smart meter programme was going to be an expensive missed opportunity. UK Trade & Investment, the small department dedicated to promoting trade, was the custodian of much relevant expertise, but it has just been re-organised unnecessarily with a loss of focus. Likewise, some of the infrastructure of leadership councils and technical advice which Vince and I built up was abandoned in the year after the Conservative win in 2015—though it is not too late to revive that.

Even though instinctively Osborne got a lot of this, his Treasury was equally instinctively wary of Innovate UK, the body which actually delivers on a lot of the items on my 10-point list. It ended up getting hefty budget cuts in 2015 with a very difficult shift of funding for start-ups into loans.

Now there is a fantastic opportunity to make all this work. May understands the power of government. She is not a pessimist who thinks government is always the problem and never part of the solution. With the easing of the fiscal rules and the return of Greg Clark to the business department there is a real opportunity.

We don’t need to waste two years going back to the beginning and re-learning old lessons. The Brexiters always insisted they wanted an open trading innovative economy. Leaving Europe may not help with that, but here is an agenda that can.

Ind 101: a crash course in Industrial Strategy

10 tests the new Business Secretary Greg Clark should apply

- Can government usefully bring together business, researchers, regulators and investors in a key business sector or technology? Identifying the best sectors for this is crucial.

- Can a trusted expert outline where key technologies may be heading and where public funds—perhaps with private partners—could plug gaps? How about a competition for a co-funded centre for doctoral training? Is there an expensive piece of kit which no one organisation can afford, but which could be funded by a public-private consortium and then rented cheaply?

- Are UK regulations/standards up to date? Can we get a market lead and attract overseas investment by drafting new ones? Do we have UK experts positioned on international regulatory and standard-setting bodies to update existing standards?

- Are there public agencies which should be encouraged to buy an innovative new product or service? Is caution or fragmentation of purchasing decisions deterring this? Can you get the responsible minister excited enough to overcome this barrier?

- Is there somewhere else in the world where there is a distinctive cluster or a major trade fair? If so, fund small businesses to go there to learn from what the competition is doing, find partners and drum up sales.

- Are there barriers to entry for new players—such as need for proof of concept or proof of market—which you can fund small and medium-sized enterprises to overcome?

- Are there specific skill shortages—for example in technicians to operate new kit—which could be met by targeted subsidy? Can we see opportunities to plan to boost our skills—such as realising our big transport projects meant it made sense to create a tunnelling academy.

- Is there a part of the country which has a cluster of expertise in a new technology? Does it get any recognition? Are the local councils and universities all backing it? Can you run a competition funding innovative small businesses in this area?

- Which are the big international businesses in this sector? Are they already investing in Britain? Are we in touch with them at the highest level? If not can we identify a minister with relevant expertise to open a dialogue and ask what we need to do to attract them here?

- Are we aware of what we need to do to promote this technology or sector in future trade negotiations? Have we got the expert advice we need to argue against the non-tariff barriers to trade which our competitors are trying to entrench?