Just beyond Muang Kham, a town in northeast Laos, there is a cave in the side of a limestone hill. It was the scene of one of the Indochina War’s greatest and least-known catastrophes. On 24th November 1968, the pilot of a US fighter jet fired a missile into the mouth of the cave where 374 men, women and children were sheltering from the hail of bombs that were daily raining down on their country. It is a deep cave, but the explosion sucked the oxygen out of the air and there were no survivors. Many of the dead were found sitting upright in rows with their eyes bulging. At the time the US did not acknowledge that it was at war in Laos—it would be another two years before Congress discovered what was going on—and news of the tragedy remains more or less unknown to the outside world to this day. The victims were hastily buried in mass graves on the hillside. So intense was the bombing that it was only possible to bury them at night.

Today, at the foot of the steps leading up to the cave there is a golden Buddha, a statue of a distraught parent carrying a dead child and a shabby little museum containing a few old photographs and a decaying wreath. Inside the cave the dead are commemorated by a series of small cairns, some with joss sticks poking out, and a little altar. An air of neglect prevails. The hillside is scattered with plastic detritus. The names of the dead are not listed: perhaps they are unknown. Lives of which no record exists. As for the pilot, he probably returned to his base in Thailand, oblivious to the destruction he had wrought.

Laos has the unenviable distinction of being, per capita, the most heavily bombed country in the world. An average of one ton per citizen was dropped between 1964 and 1973. This included some 288m cluster bombs, about 30 per cent of which did not explode on impact. Forty-five years after the bombing stopped, the hills and valleys of northern and eastern Laos are peppered with live ordnance that continues to kill and maim farmers and their families.

For many years after the war, the land was so heavily mined that much of it could not be cultivated. In order to survive people supplemented their income by collecting scrap metal, much of it live ordnance. Scrap metal dealers travelled from neighbouring Vietnam handing out cheap metal detectors and paying good money for the proceeds. Often the farmers defused the bombs themselves. “I know scrap metal collecting is dangerous, but my family must do it to live,” a farmer told Sean Sutton, a British photographer who has documented the clear-up operation in his book Laos: Legacy of a Secret.

There have been many accidents: a man chopping wood whose axe hit a bomb, killing him, four of his five children and two of his neighbours’ children; a farmer who stored his cache of scrap metal underneath his house only for it to blow up, killing him and destroying the house (fortunately his family were not home). Even now farmers ploughing their fields ignite the occasional bomb. Overall, about 20,000 people have been killed or injured since the war ended in 1975 according to the Mines Advisory Group (MAG), which have been working in Laos for the last 25 years.

Despite many warnings, Lao farmers, especially children, are extraordinarily casual about handling explosives. On occasion farmers have been spotted trying to chisel the tail-fuse out of a 1,000-pound bomb in order to earn a few dollars. A scrap metal merchant near Phonsavan, on the Plain of Jars, was recently found to have a vast quantity of live ordnance on his premises. Far from being grateful to the bomb disposal team who spent weeks removing it, he threatened to sue them for the value of the metal.

To this day, bombs are everywhere. On the streets of towns and villages across the country the vast array of ordnance dropped on Laos is on display. Hotels, cafés and travel agents have their stock of (hopefully defused) bombs ranging from those the size of cricket balls, which on ignition dissolve into hundreds of tiny steel fragments inflicting hideous injuries, all the way to enormous 3,000-pounders. In the countryside mortars can be seen holding down thatched roofs; bomb casings are used as stilts for huts or to grow vegetables. There are pots, pans, buckets, cutlery, oil lamps all made from bomb parts. At the newly opened museum in Phonsavan, a bomb-disposal officer was invited to inspect the ordnance on display and found to his alarm that some of it was still live. He offered to check over the large display of ordnance in the lobby of a local hotel, free of charge. His offer was rejected.

How did this happen to a country that was never officially at war? The answer, of course, is that the war in neighbouring Vietnam spilled over into Laos. In the early 1960s, the north Vietnamese and their rebel allies within the US-backed south began using the forests of eastern Laos to infiltrate South Vietnam. Secretly the US began to bomb north Vietnamese forces that had entered supposedly-neutral Laos. The Lao government turned a blind eye in return for enormous amounts of US aid. But gradually the war spread to the country’s interior.

With north Vietnamese support the Lao communists captured the strategic Plain of Jars. As the communists moved west the bombing intensified, but since neither the Americans nor the Vietnamese admitted they were in Laos, the war went largely unreported. It wasn’t until much later that journalists stumbled upon the huge CIA base at Long Tieng in northern Laos that the outside world began to take an interest. Long Tieng was the headquarters for an army of Meo hill tribesmen organised by the CIA. It was also a huge airbase, taking hundreds of flights a day. By population it was the second largest city in Laos, but such was the secrecy it didn’t appear on any maps. On my first trip to the country in 1972, I caught a bus up Highway 13 from the capital, Vientiane, in the direction of Long Tieng, but when one of the other passengers started calling me “bomber” I decided it was time to get off.

Under the 1962 Geneva Agreement, the neutrality of Laos was supposed to be guaranteed. But this façade soon evaporated with the assassination of several prominent leftist members of the government. The remaining leftists promptly retreated to the safety of the remote northern provinces, from where—with north Vietnamese assistance—they began to wage war on the US-backed regime in the capital. Even so throughout the Indochina War all sides were represented in Vientiane. It was the only country in southeast Asia where one could meet diplomats from North Vietnam,

China, the Soviet Union and the US, occasionally at the same event. Even the communist Pathet Lao, who were seeking to overthrow the Lao government, had an office in Vientiane in a heavily guarded compound near the main market. To complicate matters the prime minister, Prince Souvanna Phouma, was the half-brother of the titular head of the Pathet Lao, Prince Souphanouvong.

“Children depicted disturbing scenes of people and animals being blown to pieces by terror from the sky”

It was not until July 1968 that the first clues about what was happening began to leak. Jacques Decornoy, a Le Monde correspondent, became the first western journalist to visit Sam Neua. He reported that most of the town had been destroyed by napalm and that for a distance of 18 miles he saw no villages left standing. The people lived in caves and underground tunnels emerging only at night to try to plough their fields.

Meanwhile a steady flow of refugees were making their way out of the Pathet Lao zone into territory controlled by the US-backed Vientiane government. They were called “refugees from Communism.” Before long foreigners started interviewing them. One of the first to do so was Fred Branfman, an American field worker with the US International Voluntary Service who spoke fluent Lao. “Between 1969 and 1971,” he said, “I conducted hundreds of taped interviews with refugees who had fled from all parts of Laos. Their stories were consistently the same. They said their villages had been destroyed by American aeroplanes.” He also asked refugee children to draw what they had seen: they depicted disturbing scenes of people and animals being blown to pieces by terror from the sky. He later published a moving book, Voices from the Plain of Jars, illustrated by children’s pictures, in which the refugees in their own words describe what happened to them.

By October 1969, after over five years of bombing, the US Congress began to take an interest in Laos. Under exhaustive questioning before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, William Sullivan, US ambassador to Laos from 1964 to 1969, said for the first time that American planes under his personal supervision had been bombing the country. The news came as a surprise to senators, not least because Sullivan had appeared before a sub-committee the previous year and, as Senator William Fulbright put it: “The impression was quite clear that we were not doing any bombing in Laos; that whatever bombing was being done was being done by the Royal Lao Air Force.” Senator Stuart Symington told Sullivan, “You are operating a country team as our ambassador, planning and directing military adventures which Congress ought to know something about... We would like to know what was and what is going on in Laos.”

Sullivan told the committee that from 1962 to 1969 more than 200 Americans had been killed and about the same number gone missing on secret operations in Laos. Since there were not supposed to be any US combatants in Laos they were reported to their relatives and the press as having been killed “somewhere in southeast Asia.” He went to great lengths to reassure senators of the care he took to select only military targets: “we established with the Royal Lao government very clear rules which put the villages or any inhabited places out of bounds to US air activities. Now some much larger towns have an area 25 miles around them, others of medium size have a five mile radius in which they couldn’t be attacked.”

Those who lived in the areas to which Sullivan was referring told a different story. In April 1973, on my second visit to Laos, I interviewed refugees in a camp about 40 miles east of Vientiane, former inhabitants of the villages of Ban Muang and Ban Khouang in Xieng Khouang province, just south of the Plain of Jars. These people had crossed into Vientiane government territory in 1969 after living for five years under the bombing—precisely the period when Sullivan was US ambassador. “Life was good in Ban Muang,” according to the village headman. “We grew paddy rice, corn and vegetables. There were wild cattle and deer in the forest and also tigers and bears. Before the Pathet Lao had been in the village for a month the aeroplanes came. They shot at us and dropped bombs. Much of the village was burned. The planes came back many times, they came every day. Even after the village was destroyed they came back...”

A second man interrupted: “it wasn’t just the village. If the planes found anyone in the open, they bombed them. If they saw a buffalo, they bombed it. After the first day we never really lived in the village. We went to live in the forest where we built shacks and dug tunnels beside them. We slept in the huts and if the planes came we hid in the tunnels. For five years we lived in the forest. We could only go out to work in our fields between five and eight in the morning. Then the planes arrived.” The refugees said that all the hamlets around Ban Muang and Ban Khoum were destroyed. With the exception of the village headman, none had ever met an American before they came out of the forest in 1969. None knew where America was or why America was bombing them. They were, however, familiar with the types of aeroplanes used from seeing them flying overhead. Among those they described were T6, T28, F105 and B52s.

On 6th March 1970, President Richard Nixon personally admitted for the first time that US planes were bombing Laos—six years after the bombing had commenced. Like Sullivan, Nixon was at pains to emphasise that the bombing was directed at the Ho Chi Minh trail and “in response to the growth of North Vietnamese combat activities.” Of the bombing he said: “it is limited, it is requested. It is supportive and defensive.” Even on the evidence available at the time, the president’s statement was incorrect in almost every detail.

“For five years we could only go out to work in our fields between five and eight in the morning. Then the planes arrived”

All the signs are that, of the 3,500 hamlets known to have existed in the Pathet Lao-controlled regions of Laos when the bombing began, almost none were still standing when the bombing finished in February 1973. Besides these the towns of Sam Neua, Xiang Khouang, Ban Napè, Tchepone, Attapeu and Salavan no longer existed. An American congressman, Paul McCloskey, remarked: “If there are no villages, someone has destroyed them. The assumption must be that US air power has destroyed them.”

The bombing, with the exception of a few post-ceasefire sorties, stopped on 26th February 1973 following the signing of the Paris Peace Accords under which the US agreed to withdraw from Indochina. A few months later the Pathet Lao and the Vientiane government agreed to form a coalition on terms which were widely regarded as heavily favourable to the Pathet Lao. In December 1975, following the communist victories in neighbouring Vietnam and Cambodia, the Pathet Lao assumed complete control of the government and Laos entered a long period of economic and diplomatic isolation from most of the rest of the world.

The new Communist government in Laos faced many pressing problems. US aid, which until the end of the war had accounted for many times the GDP of the entire country, was promptly withdrawn, causing much of the economy to collapse. Faced with the prospect of serving years in re-education camps many of the old Lao elite left for exile in Thailand, France and America. Even at the best of times, Lao governments were never particularly dynamic, but the new masters brought with them a paralytic bureaucracy with the result that almost all productive activity ground to a halt.

As for clearing the bombs that littered the uplands, they lacked the means to do so. Returning refugees were left to their own devices. Later, with the assistance of Soviet experts, a start was made on clearing the Plain of Jars. When I visited Lat Sen, a state farm in Xieng Khouang province, in December 1985, I was told they had so far unearthed 65,000 pieces of live ordnance. A couple of American non-government organisations, the Quakers and the Mennonites ran small programmes but these barely scratched the surface.

As for the mighty power that had dropped the bombs, they showed little or no interest in clearing up and, in any case, received no encouragement from the Lao government which was suspicious of foreigners in general and Americans in particular.

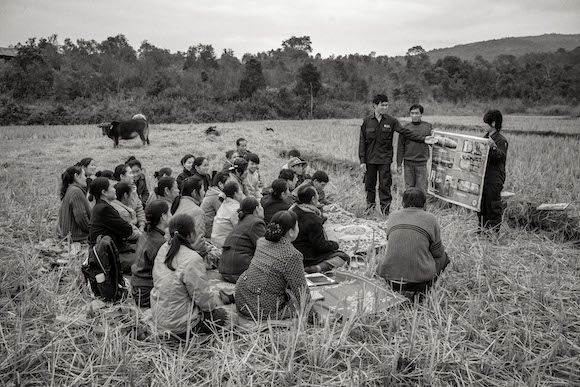

Not until the Soviet era of glasnost and the passing of the old generation of leaders did Laos start to open up to the outside world. Specialist mine-clearing organisations like the MAG and the Halo Trust now operate in the most-bombed provinces. MAG employs over 900 people, many of them women, engaged in mine clearance and also runs a programme to educate farmers and especially children about the hazards posed by these deadly weapons. In 2016 Barack Obama became the first US president to visit Laos and announced a $90m programme of assistance for mine-clearing operations. “I believe the US has a moral obligation to help,” he said. Better late than never, I guess.