I can’t look at this particular self-portrait of Vincent van Gogh without thinking about sadness. The heavy, overbearing brow, the way his deep-set eyes turn upwards towards the top of his nose. Never smiling. And so bony! His ginger complexion meant he often used deep blue as an offsetting colour, either in the backdrop or in his choice of clothes, which only adds to the general gloom. Though it isn’t a self-pitying kind of sadness, more a simple fact. His relationships, whether platonic, familial or romantic, all fractured eventually; his dreamed artist colony in the south of France never happened; it was cheaper to paint himself; that is all.

This, his self-portrait from 1889, is the only one at the National Gallery’s latest exhibition, Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, which brings together works Van Gogh made during his time in Arles from 1888 up to his death two years later. The show is meant to highlight Van Gogh’s growing interest in two archetypes during this time, the titled “Poets” and “Lovers”, who appear to us either head-on—such as in Van Gogh’s portrait of Belgian painter Eugène Boch—or more obliquely—such as in a couple walking, furtively, through a park in Arles.

Given that this time in the south of France coincided with the most productive period of his brief artistic life— which yielded some, if not all, of his most famous pictures—the National’s framing is essentially immaterial. All Van Gogh’s paintings are either better or lesser known to us. None are unknown. The peasants, the wheatfields, the cypresses, the sunflowers: all are in evidence here many times over. The irony of this is that it has made Van Gogh, himself, his own kind of archetype. All we have to do is say: ah yes, there he is, the tortured artist, such a troubled soul, what a shame! And then we can allow ourselves not to worry too much about him.

The Van Gogh cultural industry—already in full swing by the time the National Gallery acquired its first picture by him in 1924, but nowadays even more sophisticated—has only deepened our familiarity by turning Van Gogh into his own sort of world-builder. There’s Loving Vincent from 2017, a stop-motion film in which every frame is an extension of his paintings; there’s the phenomenally successful “Immersive Experience”, a theatrical light-show that lets us “surround” ourselves in his Arles and sleep in his bed; there’s even a Lego rendition of The Starry Night with a price tag of £150. More than perhaps any other painter, looking at Van Gogh’s pictures is no longer enough. We also want to occupy them.

Intuition might lead us to think that all of this is just noise surrounding the work in question. Perhaps. But I think that these iterative explorations of his work are just a different version of the same conclusion Van Gogh himself reached through the act of painting.

Painting in the open air or from life and lacking confidence to work in allegories or symbols—in other words, unable to paint what he couldn’t see with his own two eyes—Vincent’s struggle as an artist was essentially to reconcile his deep Christian faith with what was, at heart, a materialist frame of mind. In his letters, he seldom wrote about painting in any highly conceptual way, preoccupied instead by questions of colour and composition. It is only in his digressions on faith that bring him—and us—close to any sort of artistic manifesto.

Through painting, Van Gogh sought evidence of God’s thumbprint upon His creation, but without trying to embellish what he saw. It was less about painting the world anew than uncovering what had been there all along. When such a search failed to find any evidence—as it must—the only rational response was doubt, and sadness.

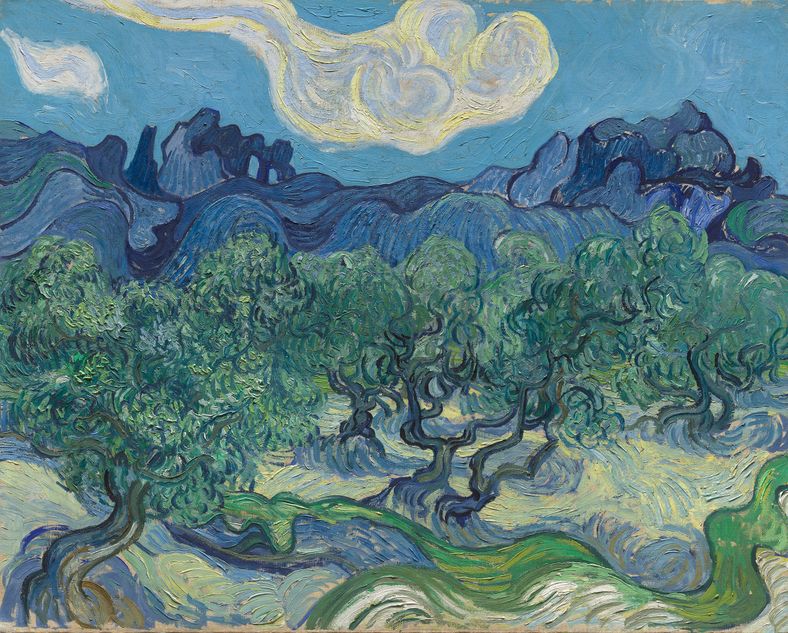

But doubt begat a redoubled search, which begat more paintings. In the final room at the National Gallery, we see Van Gogh painting the same field of olive trees five times over. Each has its own distinct character, colour and mood. In some, the trees are basked in a warm orange, the trees themselves seeming to expand and shimmer with the beating heat. In others they are hunched down and wintry, mottled in blue and green, even as they remain in full leaf.

From this endless “journey” in painting, as Van Gogh sometimes called it—this constant reiteration, this intimate familiarity with his subjects—he managed to make godless reality its own kind of consolation. “I can do without God in both my life and also in my painting,” he wrote to his brother Theo in September 1888, “but, suffering as I am, I cannot do without something greater than myself, something which is my life—the power to create.”

Art allowed Van Gogh to be more than just his sadness; just as his art allows us to transcend our own sadness, too. Deep blue is still a sad and gloomy colour, sure. But in Van Gogh’s eyes it also became the colour of the infinite.

Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers is on display at the National Gallery from 14th September to 19th January 2025