I first encountered Moroni’s painting on a drizzly Tuesday morning before an interview for art school. I was young and new to London. I had time to kill and nerves to settle, so I headed for the National Gallery. I stepped from the grey slabs of Trafalgar Square into the main entrance and, lulled by the meandering crowds, moved through grand rooms.

I found myself in a central space lined with bright marble where one large painting was holding court. It was Holbein’s The Ambassadors, with its telescopes, lutes and globes, its pair of statuesque, slightly bored-looking men and its shimmering backdrop the colour of a freshly cut lawn. I tried to make my way towards it, but the crowd was stubborn. Some were gathering by the painting’s right-hand corner, craning so they could skim its surface and take in the famous optical apparition of a skewed skull.

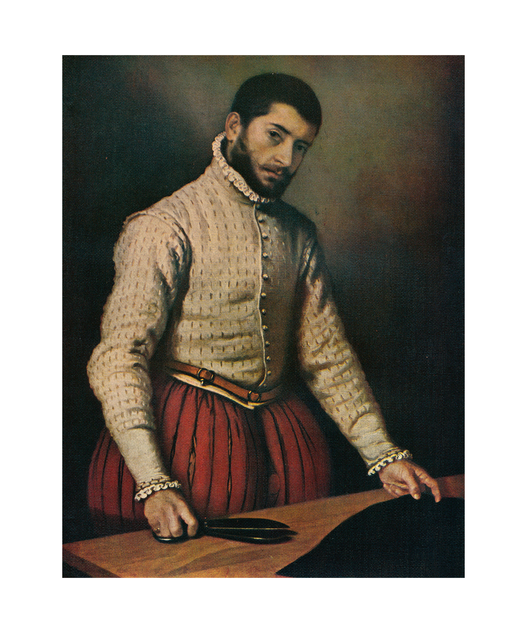

I tried to get a look at the illusion myself, but couldn’t break through the crowd. Instead, I stepped back from The Ambassadors’ right edge and was suddenly confronted by the stare of a Mediterranean man. Compared with the bright crispness of The Ambassadors, this painting descended on me like dusk: the man’s black-brown eyes and slightly sallow face emerged from an expansive greenish-grey. He was not quite life-size, yet still taller than me. He was handsome, but not vain. His hair had been cropped, but not recently. Like his beard, it was looking slightly unkempt.

Those huddling to see the Holbein faded as I became absorbed in this other painting: I studied this man and in turn he studied me. His stare was arresting, quiet and direct. Simultaneously he seemed to say “I dare you” and “How may I help you, sir?”

My eyes darted down to the large pair of scissors in his hand. The cutting edge of the outer blade caught the light in a hairline streak of white paint. Resting beside his other hand, on a table, was a bolt of cloth. Faint lines of chalk ran along the fabric, echoing the highlight on the scissors’ blade. It was then I realised this man was a tailor, and that his gaze was not threatening but calculating; he was sizing me up.

I took in his clothing: it had flair, but was practical and looked well worn. There was the dusty cream doublet with darts, the white cuffs frilled like the tendrils of jellyfish. Then there were the slender diamonds of yellow fabric bursting from his stuffed scarlet hose. The ring on his right hand shone, but only faintly. He wasn’t dressed so much as upholstered. When I took a step back, all these telling features seemed to blur a little: it was actually quite a modest composition, with its sombre autumnal palette of dull reds, golds and stone.

In a rush, the noise of the room returned and I decided to leave, back into the drizzle. As I walked, I couldn’t shake the memory of that unnamed tailor’s stare. He was present and unflinching, yet holding something back. He returned every dissecting glance of mine with one of his own, more exacting and yet also more casual. He wouldn’t let me settle into the gentle rhythm of spectatorship; his teetering expression forced an encounter. Over years he had trained his gaze. He knew how to look.

Since that meeting I have returned, at least once a year, to see The Tailor. I know Room 12 and its ever-present crowd of Holbein admirers well, but instead I skirt them and take up my position in front of Moroni’s shadowy figure. On my last visit, it looked as though the tailor had noticed my threadbare coat. Perhaps he saw an opportunity to make a sale.