Is Guernica (1937) the most famous piece of political protest art ever made? Probably.

Depicting the wailing, the dead, the gorged and dismembered, Picasso’s Cubist mural is so ingrained in our collective consciousness that, while it technically protests the specific bombing of a specific town by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, it transcends the universal, standing against the corrosiveness of all war, all violence. When Guernica arrived for its first and only showing in the UK, at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1939, it drew 15,000 visitors within a week.

“You can’t measure the impact of Guernica,” the British artist Peter Kennard, whose exhibition Archives of Dissent is currently also showing at Whitechapel, told me by phone. “It’s not like if you advertise baked beans, when you can measure how many extra tins are bought. There have been countless reproductions. It’s been used on countless demonstrations. You just know that Guernica is an amazing antiwar image that’s going to always be with us.”

Since becoming politically engaged during the Vietnam War, Kennard has made the art of protest his life’s work. Through his use of clever photographic collage, he has crafted striking imagery in support of causes such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and Anti-Apartheid, as well as to draw attention to the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. One of his most famous collages—made with longtime collaborator Cat Phillips—is Tony Blair (‘Photo Op’) (2006), depicting the then prime minister taking a selfie, all smiles, in front of a devastating explosion. Some might say the image gruesomely epitomises Britain’s entry into war with Iraq, led by Blair. Full-throttle, talon-sharp, powered by outrage; the work is an iconic image of protest. “I get accused of propaganda, but it’s seeing everyday images in a different context,” Kennard tells me. “Young people aren’t necessarily going to read complex books about capitalism. If they see an image that spurs them into thinking critically, they might join a protest group or take action.”

Much of the works at Kennard’s Whitechapel show date from the 1970s to 1990s—Values (1973), The Gamble (1986) and Mandela (1990)—and looking at other protest art made at this time reveals a shared vernacular composed of a gritty, almost DIY aesthetic. In 1989, the American graphic artist Barbara Kruger created Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground), a work still used today as a symbol for abortion rights. Originally printed as a flier for a march on Washington DC staged in 1989, Kruger’s image shows a black-and-white photograph of a model’s face. The face is split down the middle, with the left perhaps representing surface perfection, while the right features a negative exposure, almost as if the model were being hunted down through night-vision goggles. The Futura bold font, white on danger-alerting red, is Kruger’s trademark, imprinting the image with its urgent message.

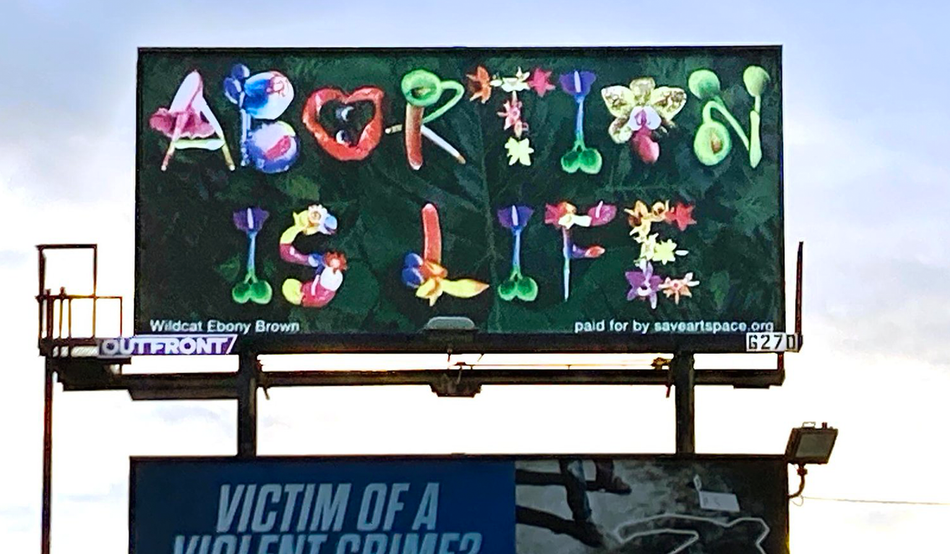

What’s most striking about the Kennard show, however, is how it underscores the extent to which protest art has changed over the decades. Particularly in the US, protest art in recent years has taken on a much slicker appearance—as, indeed, has advertising. Perhaps the two are aligning? Back during the US midterm elections in 2022, Swedish conceptual artist Michele Pred curated a series called “Vote for Abortion Rights” with the nonprofit SaveArtSpace. Featuring work by 10 artists—among them Shireen Liane, Bud Snow and Ebony Wildcat Brown—on 19 billboards in 14 cities across 12 states, the series was part of a campaign in support of sustaining abortion access after the downfall of Roe v Wade. In the billboard by Brown, the words “Abortion is Life” emerge from a dense backdrop of lush leaves, spelt out in vibrant, almost hallucinatory flowers, tightly furled buds and stamens representing testicles and penises.

In the lead up to this year’s US presidential election, the artist and academic Beverly McIver adopted a similar approach to convey her own pro-choice message, presenting her work on billboards across the swing states of Florida and Georgia. Vote Black Beauty shows an anonymous woman (her tangerine bob reminiscent of Leeloo from Luc Besson’s 1997 sci-fi film Fifth Element) whose form is picked out in black. Across her limbs and pelvis, leaves and petals twine. The flowers—orange, blue, pink, yellow and white—bloom. Above the woman’s head is the simple word “VOTE”, with the “T” replaced by fallopian tube and uterus.

McIver tells me over email that the opportunity to do the work arose when People for the American Way, a nonprofit founded in the 1980s to counter rising right-wing extremism, invited her and two dozen other artists to create works that helped “get the word out creatively in key swing states via billboards and murals”.

“Artists have historically used their voice—via artwork—to incite change and shed a light on what is right, and wrong, in the world,” she says. “What keeps me going? Making more art, and having the ability and freedom to make more art in a world where freedom of expression is appreciated, not condemned.” The campaign is an attempt to re-interpret concepts associated with Trump’s Maga movement—such as “freedom”, “patriotism” and “the American way”.

Though, despite the ubiquity of more professionally organised, campaign-led art this US election cycle, it remains hard to quantify the tangible power of protest art—percolating as it does on its own timeline, where you can’t measure “how many extra tins have been bought”, to borrow Kennard’s words. One thing that’s striking, however, is perhaps a growing feeling that—in such a fractious political climate—there might now be some subjects, or some people, who are simply beyond its effective scope. In my conversation with Kennard, he told me he now avoids making images of Donald Trump, having at one time depicted him with a submarine coming out of his head (Sub-Trump, 2018). “Trump is already a made-up image,” he says. “It’s quite difficult to present, represent or interrogate that. He’s a composite of all the horrors of our time. He’s put them into himself.”

Kennard’s inability to make imagery of Trump—given his powers and Trump’s threat—seems somewhat surprising. Maybe this is the state of play of what’s to come in protest art. As the fantastical, the hyperbolic and the fractious have become commonplace, with Trump selling sneakers, watches and a branded Bible, satire and irony have become increasingly redundant as protest art’s key power players. What remains? In the face of such distortion and canker, perhaps it is love, humanity’s most basic, universal human value, that holds any remaining power and sway in protest art. Perhaps flipping the script with positivity, as per Brown and McIver’s beautifying treatment of abortion—a subject long made ugly by its enemies—is the answer. We can only hope.