We are all interconnected, the thin membrane between us permeable, porous, liable to leaks, spills and cross-contamination. We are vulnerable to disease, but also open to love. These ideas sit at the heart of Jenn Shapland’s new collection of essays. Taken together, they’re a neat metaphor for how she’d like humankind to relate to the world—in a capacious, respectful, generous, inclusive fashion. She wants us to tread lightly as we go about our lives because the planet demands our care.

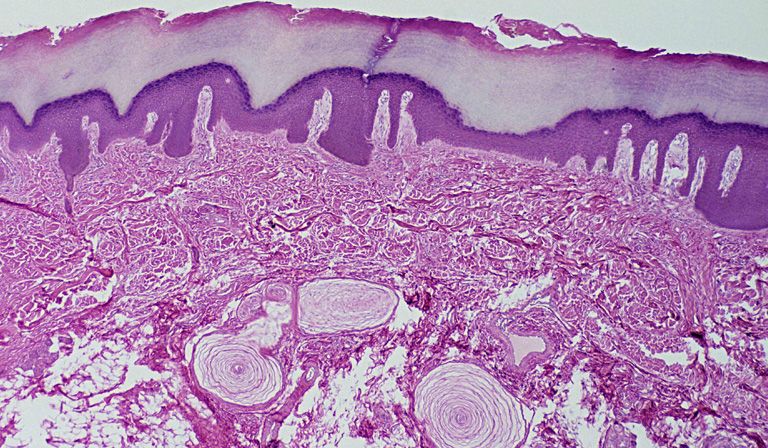

But these ideas about porosity and sensitivity are also literal. Shapland, it turns out, has thin skin, a rare dermatological condition. She breaks out in rashes, flares and itches; reacts to every pollutant with an instant migraine; is allergic to her own sweat. Taking Ernest Hartmann’s test to learn how psychologically robust she is, she discovers that she is thin-skinned in the realm of emotions, too: she feels things keenly. “A layer is missing between me and the world,” she writes.

A few years ago, Shapland relocated from Austin, Texas to Santa Fe, New Mexico, trading in her job as an archivist for space to think and the freedom to pursue an alternative lifestyle, far from the edicts of capitalism. Perhaps the big skies and desert air would be kinder to her skin? New Mexico is cheap, which has long been part of its appeal to artists. If you want to write or paint full time like Cormac McCarthy, Julia Cameron, Agnes Martin or Georgia O’Keeffe, the mesas of the American southwest are an attractive proposition. But the low-rent living has other causes: when Shapland and her girlfriend Chelsea (a smart-talking foil in many of these essays) fell for a rental property not far from Los Alamos, the existing tenant led them to the aquifer out back and said “Uranium,” adding, “It’s fine, just don’t open your mouth in the shower.”

The Earth, too, has thin skin. No matter how deep we bury industrial effluent, the toxins seep out again. And because the impacts of our ecological crisis are skewed, the poor, displaced and marginalised are first to get hurt. When the US government cleared the Los Alamos area in 1942 to make way for the Manhattan Project, in what Shapland terms “an act of colonisation”, ancient Pueblo structures were dug out and plutonium stored in them. Over the next two decades, 20,000 gallons of nuclear waste were dumped into the Los Alamos and Pueblo canyons. Radioactivity levels in local households are still 600 times higher than normal, sending childhood death rates from cancer soaring.

In radioactivity, Shapland finds another “literalised metaphor” for the “unseen forces” that hide in plain sight, quietly eroding the boundaries that we imagine exist between ourselves and the world outside. Shapland is clear about this imaginary line, insisting, “there is no ‘Outside’.” Her pains to include native American and black American voices from traduced communities, and her sharp deployment of a queer analytical perspective, suggest that there’s no “Them” either. No other, defined by class, race, gender or sexual orientation.

These essays are a triumphant celebration of the thin-skinned perspective

Millennials generally get a rough ride for feeling too much, for being “snowflakes”, lacking resilience and being obsessed with positional identities. But these essays are a triumphant celebration of the thin-skinned perspective.

If we only acknowledged that we’re fundamentally permeable—that we don’t know, as Shapland puts it, “where the edges of things are”—we might access a new way of looking. Interrogating this boundary-blurring from multiple angles, Shapland follows the book’s title piece with “Strangers on a Train”, a study of the white fear that finds its apotheosis in a cultural desire to protect white females—especially young, blonde ones—from dark and dangerous forces, where the very idea of subjugation is tangeld up with the raping or killing of women. Shapland grew up in an affluent town on Chicago’s north shore. Don’t talk to strangers, don’t walk alone after dark, don’t dress sexy, she was told. It left her feeling unsafe and then hating her own vulnerability. But these fears are misplaced, she suggests: a projection of colonial guilt, for which women pay the price of their freedom.

Cultures that exert control over women through fear are more or less universal, but the particular inflection this trope takes in the US consistently implicates the black man as threat. The link dates to the days of lynching, when a black man could be hung for simply speaking to a white woman. Race politics in America contaminate everything. Indeed, Shapland notes in passing how black people, thought to have thicker skins (literally) than white people, were recruited from army and prison populations by military doctors who didn’t think twice about giving them higher doses of chemicals when seeking to establish threshold levels for nerve agents, or herbicides such as Agent Orange.

Shapland leans on essayist Eula Biss to name the psychology at play. “We are afraid,” Biss writes in Notes from No Man’s Land (2009), “because we have guilty consciences. We secretly suspect that we might have more than we deserve… And so, privately, quietly, as a result of our own complicated guilt, we believe that we deserve to be hated, to be hurt.” This is the origin of white fear, recently and disastrously fuelled by Trumpistas and their QAnon associates, expressing itself in the cry to “Lock up your girls!”

In “The Toomuchness”, Shapland appears yet again to be in conversation with Biss (this time with Having and Being Had). Like Biss, Shapland draws on the capitalist critiques of the late David Graeber to pick apart her own perceived failings, as she tackles our compulsion to acquire and hoard stuff; our addiction to extraction and excess. For years, clothing was her downfall. At a time when Shapland didn’t know who she was, buying clothes allowed her to try on successive selves. “I didn’t have to be me,” she says, longing for “self-transformation through material things”. Longing, perhaps, for a second, protective skin.

Spurning conveyor-belt consumerism, Shapland turns to making her clothes, designing gender-free garments that eschew conventional form. She discovers a joyful slowness in hand-crafting things; acquires new skills; recycles what she already owns. But then, almost despite herself, she soon has a cottage industry on her hands, with people commissioning her via Instagram to sew for them. Shapland can’t escape the forces of “primitive accumulation”, no matter the trying. Even knowing that “the things we consume are eating us alive.”

With clothing, closets and tried-on identities, we’re back in the territory of literalised metaphor. Shapland’s much-garlanded first book, My Autobiography of Carson McCullers (2020), braided the dual life stories of Shapland’s gradual embrace of a queer identity with a queer biographical reading of Carson McCullers. It created a stir because, while there were rumours aplenty about McCullers’s sexuality, biographers refer to her lovers as crushes, obsessions, or special friendships. Reeves McCullers, Carson’s (likely gay) husband called them her “imaginary friends”.

Now, in writing about contagion and contamination, our essential vulnerability and our fear of being invaded and infiltrated, Shapland again draws on the sensibility of the closet as an investigative tool. Whether addressing invisible poisons, real and conceptual, or the hidden systems of capitalist and patriarchal control—or, more positively, in another essay on the power of crystals, native American supernaturalism and New Mexican woo—she yanks unseen (denied!) realities into the light and looks them in the eye.

In My Autobiography, Shapland writes: “To be outed is a violation, but it is also a moment of freedom, of honesty, of finally being out of hiding.” In Thin Skin, the closet becomes “a two-way street”—a refuge as well as a place of denial. In both cases, the closet (like the archives she once worked among) is an ambiguous ontological space, where we tidy away what we long not to know and try hard to forget about it. Although exposure to light can be damaging, Shapland ultimately judges that the archive/closet is too suffocating a place to live in.

Whereas My Autobiography of Carson McCullers is a concise and lyrical work, written in precision-tooled fragments while being seamless in its directional confidence, essay writing calls for a different register. It seeks to interrogate its own seams, expose its own mechanisms, like the modernist architecture that wears its various structural props—electric, hydraulic—on the outside. We should not expect smooth narrative flow from a good essay, but planned disruption. As Leslie Jamison writes in her introduction to the The Best American Essays from 2017, good essays spin gold out of their own failures. They metabolise them, treating them as “a trampoline rather than a straightjacket.”

We should not expect smooth narrative flow from a good essay, but planned disruption

A potential downside of writing like this is that it can overwork the reader, making them reach too hard for narrative reward. At times, these essays are rambling, slow to arrive at their point and uncertain in their connections. I struggled with the many-pronged paths taken in the book’s final essay, which, despite its seemingly tongue-in-cheek title (“The Meaning of Life”), does actually attempt to figure it all out. What saves the day is Shapland’s humane, intelligent voice. She is, quite simply, excellent company.

All that said, the last essay does eventually join the dots in exploring alternative ways of living, free from the yoke of the corporate-capitalist-patriarchal monolith that hoodwinks us into thinking we are individuals and not a collective, impreganable rather than permeable. Wanting to live differently is why Shapland moved to Santa Fe in the first place—choosing the artist’s way of life, electing not to have children.

The book ends with a bravado call for being child-free, with queer lifestyles suggesting we can “be enough” ourselves, alone, without striving for legacy or “futurity”—without buying into the invidious notion on which capitalism depends, that we accept a desperately degraded present in return for the (fictitious) promise of better to come.