Driving high over the South Pennines was a euphoric experience for me as a student. As soon as I hit the M62 on my way back from pit village Northumberland to the bright lights of Liverpool University, I would slide the well-worn cassette of the Stone Roses’ eponymous debut album into the tape deck of my threadbare Vauxhall Corsa. Mani’s bassline would cause instant gooseflesh, John Squires’s Stratocaster quickened the pulse, and by the time that Ian Brown reached the crescendo of “I Wanna Be Adored” or “I Am the Resurrection”, I’d feel practically airborne as I sped past places like Brighouse and Cleckheaton.

But the album’s wistful folk number “Elizabeth My Dear” had a different register. As a history student, I was intrigued by the echoes of 16th-century hanging, drawing and quartering in the lines:

Tear me apart

And boil my bones

I’ll not rest

‘Til she’s lost her throne

But which Elizabeth was the song referring to? It’s assumed to be a republican rejoinder to the House of Windsor, but I detected echoes of the deep past—not least the last great armed rebellion of the North versus the South, against Elizabeth Tudor in 1569, and the state-sponsored butchery that followed.

The motives behind the Rising of the North were mixed. Rival regnal claims were a serious business, but so too was the sense of regional grievance from a largely Catholic north bridling against the Elizabethan project to impose Protestantism and assert the power of the Tudor state across every part of her kingdom.

But perhaps the worst insult to northern pride was the burning of St Cuthbert’s banner by the fanatically puritan wife of the dean of Durham Cathedral in the 1560s—the same embroidered standard that had led the northern, Catholic resistance to Elizabeth’s father in the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536.

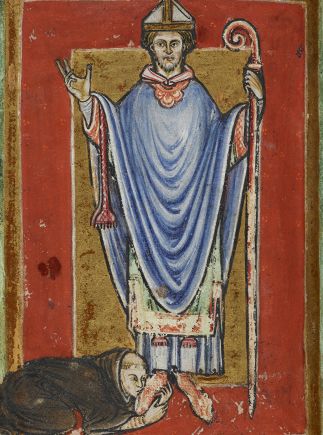

It’s hard to overstate how important St Cuthbert was to the North of England. The historian Tom Holland has described him as “a figure of awesome and terrible power, who was valued by the Northumbrian royal dynasty as a kind of Merlin or Gandalf”. The glories of his shrine in Durham Cathedral were rivalled in England only by those in Canterbury, and the healing power of his relics were the Pfizer vaccine of its day. In Chaucer’s “The Reeve’s Tale”, the northerners swear by St Cuthbert, not by St Thomas Becket. Cuthbert’s banner was carried in battle by Northumbrian troops against the Scots, and after the English victories at Neville’s Cross and Flodden Field, the swords and armour of the captured or slain Scottish kings were placed on St Cuthbert’s shrine in homage.

Some of these recurring themes of Northumbrian history—of glorious creativity and confidence alongside defeat, decay and subjugation, and the place of a totemic figure such as Cuthbert within that story—are the central motifs of two recent books from two Northumbrian writers. The first is Cuddy, an unusual retelling of the life and legacy of St Cuthbert by Benjamin Myers through prose and poetry. The second: Alex Niven’s The North Will Rise Again, a lively cultural and political history of the lands between the Tweed and the Mersey–Humber line.

When I was growing up in the Northumberland coalfield, a “cuddy” was a pit pony, like those who lived in retirement near us by the railway line. It was also the nickname for men called Cuthbert—not that I knew any, other than Cuthbert Cringeworthy in The Bash Street Kids, or Lord (Cuthbert) Collingwood, the vice admiral whose giant statue still surveys the mouth of the Tyne for enemy shipping. The saint himself lay in the great “Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham”, an icon of the Northeast like the Tyne Bridge and the Angel of the North, and described by John Ruskin as the eighth wonder of the world.

Benjamin Myers is an award-winning author and journalist whose output has ranged across the themes of nature and landscape, history and memory, and the meaning of place in modern Britain. Though now living in the Wuthering Heights country of the Upper Calder Valley, he hails from County Durham, and truly knows the character of the people and places he writes about in Cuddy.

Alongside Cuthbert’s presence, much of Durham’s emotional power derives from its ancient foundations, a palimpsest of Anglo-Saxon, Norman, Georgian and Victorian building; and the way Myers tells the story of the devotion to Cuddy down the centuries is similarly layered. It begins with a spare, poetic account of the journey of Cuthbert’s body—which, famously, did not decompose—away from its exposure to Viking sea-raiders on Lindisfarne to its final resting place on that wooded hill on a loop of the Wear. Then comes a The Name of the Rose-style killing in the woods of Duresme, and an account of the hundreds of Scots who died in the cathedral as prisoners of Oliver Cromwell. A haunting tale follows of an Oxford don called to superintend Cuthbert’s exhumation, done in the manner of an MR James ghost story. The novel ends with a tenderly observed portrait of the precarity of contemporary life for so many in the left-behind places of County Durham, and the Cuthberts that still live among us.

Myers has a poetic sensibility, and as a writer he enjoys the snap and crunch of words, and the way they can summon an atmosphere, even just from the strange place names of Northumberland: “Etal, Duddo, Twizell, Unthank…” Although no believer, he also conjures the ambience of sanctity that emitted from Cuthbert in life and in death and that sense of his time as an anchorite, walled in on Inner Farne, having opened a portal to heaven.

A rheumy slit glued shut.

My eye.

A gate against eternity.

I open it.

All is as was; stone, sea and sky

Pouring in

But some of the prose tries too hard: “a sun that bakes loaves of bread in the oven of forever” made me wince, and chants of “o Cuddy Cuddy o… o Cuddy sainted soul” sounded awkward and unconvincing. But Myers is a natural storyteller, and if his more experimental writing can be patchy, his descriptions of the transit of the incorruptible “Corpus Cuddy”—and the chafing of the all-too-corruptible balls of the monks who humped his bier across the edge of the former Roman Empire—is genuinely memorable.

But why was Cuthbert so venerated in Northumbria? His much-chronicled holiness can seem incomprehensible 14 centuries later, but there was something in his personality that resonated with a people whose own character still feels distinctive. That Cuddy had been a warrior in his youth, before taking up the cross, meant a lot for a border region soaked in blood and with a martial tradition that persists to this day. There are shades of cartoon Geordieness in some accounts of his life. Saint Bede said he would “upbraid the monks for their softness”, while he preferred to spend his evenings knee-deep in prayer and the freezing waters of the North Sea, with only raw onions for sustenance. One 14th-century manuscript even claimed that the young Cuthbert “pleyde atte balle with the children that his fellowes were”—so he was clearly a lad who enjoyed a kickabout.

But it was Cuthbert’s kindness and patience that made him so loved. Bede recorded that he was “quick to reprove wrong-doers, but his gentleness made him speedy to forgive penitents”, and this saint came to be so associated with Durham that the county was almost called Haliwerfolc—“the folk of the holy man”—like Norfolk or Suffolk. The land between the Tyne and the Tees was ruled by Cuthbert, even while dead, as a necrocracy, and then as the only Prince Bishopric in these islands, quasi-independent and curiously detached from the rest of the country.

How are the holy man’s folk—and those of the wider north—faring now? As a native of Northumberland, a lecturer in English literature at Newcastle University and a keen observer of that wider north in the pages of New Left Review, Tribune and the Guardian, Alex Niven is well placed to answer.

His latest book, The North Will Rise Again, attempts a wide-ranging cultural history of the North of England over the past century, with an emphasis on popular music and the higher-brow art forms of literature, poetry and architecture. This is interlaced with a memoir of the author’s early life and thwarted career as a musician, as well as a righteously angry critique of recent British governments—all of which builds towards a polemical conclusion in favour of greater political independence for a North that is increasingly poor, marginal and unhappy.

Niven’s argument is that the North is “a place of endless subtlety, exceptional generosity, fierce love and utopian possibility”, and that if it “has meant anything over the last 200 years it has meant progress”. As evidence, he locates the North as perhaps the preeminent site of modernism in the 19th and 20th centuries, and describes how the surging energy of northern industries had a decisive effect on an avant-garde of artists, musicians and writers.

As a cultural critic, his grounding of British literary and artistic modernism in the industrial North of England makes up the strongest sections of the book. Niven skilfully connects Wyndham Lewis’s northwards-looking BLAST magazine and the Vorticists’ love of concrete and machinery with Yevgeny Zamyatin’s inspiration in the “grand mechanised ballet” of Tyneside shipyards, Aldous Huxley’s formative visit to the Imperial Chemical Industries’s huge plant in Billingham (which “opened the doors of his perception”) and on to the influence of industrial Teesside on the aesthetics of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

He well evokes the white heat of 1960s Tyneside, too, where the plate glass of Newcastle Poly jostled with local political overlord T Dan Smith’s dazzling Nordic Civic Centre; where Allen Ginsberg conducted bardic rituals in the Morden Tower on the city walls and Bryan Ferry strutted in stylish threads from Marcus Price; where Alan Hull experimented with psychedelic substances in St Nicholas’ Mental Hospital and “broke through to an otherwise inaccessible realm of northern consciousness: an exotic world of artistic freedom above and beyond an often hopeless state of mind”.

Niven’s analysis is influenced by an atypical upbringing as the child of radical academics, and he writes movingly of his late father listening to German space rock, reading Ursula K Le Guin and tending his ganja plants in his geometric pod greenhouse on the edge of the bleak Northumbrian moors. So it makes sense for him to think of the North’s “mainstream cultural tradition” as being “one of modernism and futurism”, and even to dwell on the work of the poet Basil Bunting and artist Victor Pasmore.

As influential as these artists were in northern intellectual circles, however, such an emphasis leads to an unbalanced understanding of northern culture. Niven concedes that not everyone shares his enthusiasm for “radically different forms of cultural being” and notes there are “plenty of Northern conservative exceptions to the rule, as anyone who has ever been to Harrogate or Knutsford knows all too well”. But Northern conservativism isn’t confined to these untypically wealthy enclaves and has always been a key feature of northern political culture—from the North’s unmatched response to Kitchener’s call in 1914 to the Durham miners who thwarted Britain’s entry to the nascent European Coal and Steel Community in the 1950s, and on to the strength of the Brexit vote in the “Red Wall”.

Taking the long view, we might say that the history of the North of England is a litany of defeats at the hands of the South

This is a blind spot for Niven, and although the book’s political prescriptions run to some length, while still being lightly sketched—“the UK’s political geography will have to be firmly overhauled” and “northern revival must be a radical, even revolutionary project”—it’s noticeable how seldom the hoi polloi intrude into his narrative. “Scousers and Geordies love shopping, clothes and the trappings of weekend glamour,” he sniffs, “to an extent that often borders on open mania.” And after door-knocking during the 2019 general election, he dismisses the appeal of the insurgent Conservatives as “a mixture of morbid curiosity and vague fondness for the clownish media persona of Boris Johnson”. Was that it? Their trust may have been misguided, but might they have been voting for something positive, such as the restoration of industry?

I agree with Niven, though, that the North is restive. The new mass of elected mayors—across the “city regions” of Liverpool, Manchester, West and South Yorkshire, and, from 2024, the Northeast—has created a new locus of power and influence. In the words of Walt Whitman that appear on the banner of Chopwell Miners’ Lodge, it will be up to them to “take up the task eternal” of patiently renovating the civic structures of the North and rebuilding the alliance of Northern England, Wales and Scotland as a counterbalance to the hoarding of financial and institutional power in the South (until recently, this task was the main purpose of the Labour party, too).

Taking the long view, we might say that the history of the North of England is a litany of defeats at the hands of the South: the Harrying of the North, the Wars of the Roses, the Catholic rebellions of the 1500s, Civil War and Jacobite failure, Peterloo and the Chartists, and the General and Miners’ Strikes. But there have been rare victories. When Thomas Cromwell sent his royal commissioners to seize the wealth of the church in Durham and strip Cuthbert’s shrine of its gold and jewels, they sought further riches inside his coffin. Planning to toss away his bones, they smashed their way in with sledgehammers, but were shocked to discover, “contrary to their expectation” (according to David Willem in St Cuthbert’s Corpse: A Life After Death), that his body was still incorrupt after 800 years and that they had broken one of his legs.

So although they managed to spirit the Lindisfarne Gospels to London—where they languish still, like Northumbria’s Elgin Marbles—Cuthbert is still there, a unique figure in the history of English Christianity, radiating the power of Northern resistance.