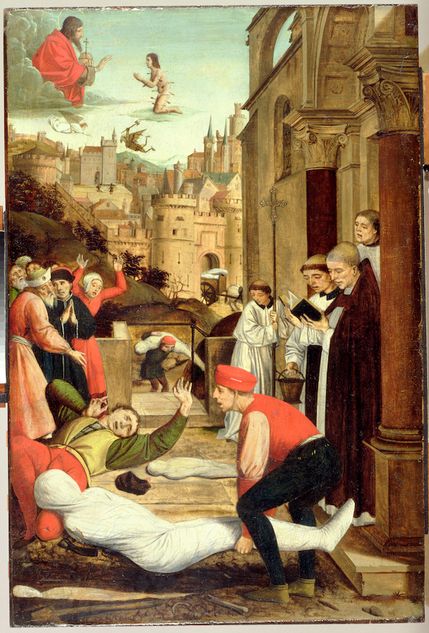

Everyone loves a good disaster. As Niall Ferguson writes in this sparkling, provocative and entertaining book, “the end of the world… has been a remarkably recurrent feature of recorded history.” Religions teach us that we are all doomed. For Jews, Christians and Muslims, the end of times will be upon us all—and woe betide us if we are not ready to meet our maker. Other faiths, like Buddhism and Hinduism, offer a little more hope, promising that although we are all doomed, we’ll go back to the beginning and start again. And then there are secular belief systems like Marxism, says Ferguson, that offer their own prophecies and visions of apocalyptic fulfilment. As the wheels of the Russian Revolution began to turn, some automatically likened Lenin to the Antichrist: ideas about the end of the world are ubiquitous.

Expectations of disaster, however, are more based on fears than on realities. It depends how one conceptualises time. It is true that from a geological and cosmological perspective we are running out of time on Earth. The good news, though, is that the planet has around a billion years or so to run. Whether humans will be around to see the end is another matter for, as Ferguson reminds us, in the grand scheme of things our species has not been around for very long.

Ferguson is intrigued by the question of how to reconcile fears of doom with the very real problems, challenges and disasters we regularly face. He sorts all of these into typologies such as “grey rhinos,” “black swans,” or “dragon kings” that some readers might find simplistic, annoying or both. Forget economists talking “with increasing absurdity” about V-shaped, W-shaped, K-shaped or “Nike swoosh-shaped” recoveries, says the author; the slow recovery will instead “be shaped more like a giant tortoise.” Historians flagellate themselves and each other often enough about labels, and one person’s jargon is another’s catnip. But this is Ferguson’s style, and there is surely nothing wrong with trying to differentiate between how and why devastating events and episodes take place.

Ferguson describes the book as a “general history of catastrophes.” It fizzes with ideas and nuggets of information, often scattered as if falling from the author’s pockets. We learn that states with higher infant mortality are seven times more likely to suffer from internal instability; we discover that, at the start of the 20th century, men in England on average drank 73 gallons of beer per year and around a gallon of wine; we find out that British administrators sent overseas at the height of the empire had significantly enhanced chances of dying compared to those staying at home—unless they were sent to New Zealand, where life expectancies actually rose.

The author is formidably well read and culturally curious, mixing references to Dad’s Army, Wagner and science fiction, with statistics on American condom use, Chinese flight schedules, bang up-to-date research on the 6th-century Justinianic plague and mortality rates for Extremadura (as well as other provinces in Spain) during the Covid-19 crisis. The pace can be fast and furious, over a couple of pages jumping from parallels between Nazism and the Anabaptists of the 16th century to the fall of the Soviet Union, or from the British legacy in India to President Erdoan’s dreams of an Ottoman revival. Ferguson expects his readers to keep up.

He settles scores, too—which depending on one’s disposition is either entertaining or a distraction. Ferguson is not a devotee of Greta Thunberg, the “child saint of the 21st-century millennialist movement,” while he also pokes fun at conservationists tempted to celebrate the global lockdowns and the “anthropause” that has spared hundreds of millions of birds and millions of other animals “their usual massacre at the hands of human motorists.” There are swipes at “woke” ideology at universities, at those who tore down statues of slave holders and Confederate generals, and at American teenagers taking to social media to accuse their parents of racism, though these have little to do with doom and disaster—unlike the Democratic congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s statement in 2019 that “the world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change.” Let’s hope she is wrong.

Ferguson’s combativeness is not to be confused with having a poor aim. Some of his judgments and criticisms are sharp and make for uncomfortable reading for those who live in the liberal bubble. Barack Obama was foolish to not only dismiss but mock those demanding that the US take the threat posed by Russia more seriously; the share of total net worth held by the top 1 per cent accelerated dramatically under Obama, unfettered, unchecked and facilitated by his administration’s fiscal policies. And then there is the doubling of US opioid deaths between 2008-2016, which Ferguson notes not only took place while Obama was in the White House, but for which he has been “assigned almost no blame” by the media.

As for Trump, doom embodied for many liberals, it’s no use just shrieking denunciation. His support came from those who had been let down by people who sounded progressive but had actually overseen policies that not only failed to protect workers and their jobs, but facilitated their offshoring to China and elsewhere. One can hardly expect those who had lived through the “carnage” of recent years to stand by and hope things would improve, as if by magic.

There are plenty of examples of poor decision-making in the book, some of which make for harrowing reading. The US government did almost nothing to fight Aids long after the scale of the pandemic was clear. Reagan would not even mention it for years, and (disgracefully) Congress banned the federal use of funds for Aids prevention and education campaigns as late as 1987. After Hurricane Katrina there was an unnecessary loss of life, suffering and hardship because of pathetic leadership and bureaucratic infighting, and the pattern has been repeated during the current coronavirus pandemic—to which most of the last quarter of the book is dedicated.

In the case of Covid-19, while Trump and Boris Johnson do not emerge entirely blameless, responsibility is laid at the door of squabbling agencies competing with each other, bureaucrats believing their own press releases and decisions not being made in time, or at all. How could it be, asks Ferguson, that Silicon Valley with its resources, resident geniuses and problem-solving ethic did not step in? Big Tech lawyers stood in the way, he says, for fear of opening up litigation around privacy concerns. It is bleak indeed if Ferguson is right, that tech titans were worried about saving their own legal backsides, rather than the lives of hundreds of thousands of people who have died in the US alone.

Ferguson’s point is that incompetence or, even worse, blind faith in flawed systems, lies at the heart of most problems humanity has faced. There is little that people can do about earthquakes, tsunamis and other “natural” disasters—some of which have been almost biblical in scale, such as the 16th-century Wei River earthquake that killed 800,000 people, or floods in South Asia in 1970 that killed half a million. But even these disasters, the author reminds us, can be laid at the door of the people who built houses along a fault line or a shoreline susceptible to tsunamis.

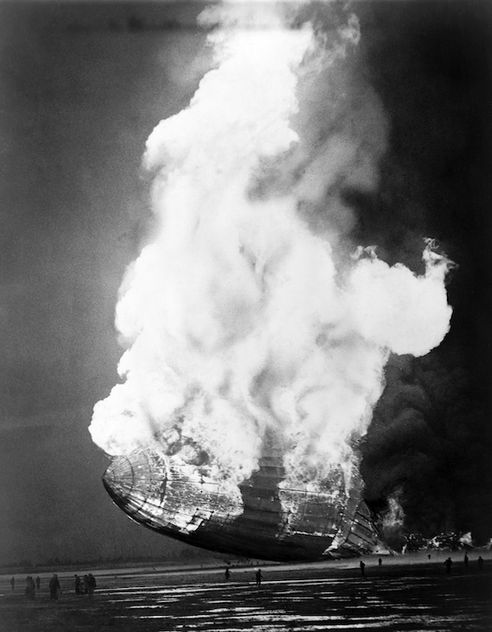

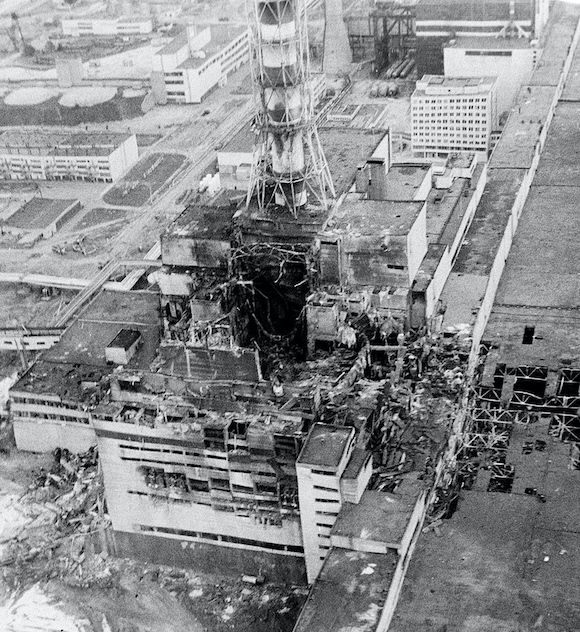

To that extent, we are our own worst enemies. The reason the Titanic sank was not that the iceberg did anything wrong or was in an unusual location, but because of human error and an inability to understand risk. Likewise, the Hindenburg disaster, the meltdown of the reactor at Chernobyl and the failure of the Space Shuttle Challenger were the results of basic mistakes. Sometimes steps taken to iron these out became themselves part of the problem: Ferguson asks if the awful collision of KLM and Pan Am jumbo jets at Tenerife airport in 1977 should be blamed on new work regulations issued in the Netherlands a year earlier, shaping the Dutch pilot’s fateful—and fatal—rush to get into the air. Misregulation, he suggests, can be as much of a problem as failure to regulate.

Globalisation ramps up the capacity for disaster. The subject of Ferguson’s last book was network theory. Here he explains the importance of technological revolutions, singling out how railways brought about what one 19th-century historian referred to as the “annihilation of distance,” while improvements in shipping speed reduced transatlantic crossings from several weeks to 10 days in a matter of decades. Such transformations brought us all closer together, thus making us all more vulnerable to new problems, and especially to the spread of disease—as Ferguson puts it, “one damned microbe after another.”

“Globalisation has brought us closer together, thus making us all more vulnerable to the spread of disease—it’s one damned microbe after another”

Much of Doom, then, is focused on how decisions get made and who makes them, and also on how our own misunderstanding contributes to the real risks that we face. Ferguson is unsparing about the industry of prediction. The IMF, he says, anticipated just four of 469 national economic downturns between 1988 and 2019. The “super-forecaster” Philip Tetlock estimated that there was only a 23 per cent chance of Brexit and, later, a mere 3 per cent chance of mass infections in a limited time period early on in Covid—two supposed improbabilities which soon turned into actualities. Healthcare systems in countries like the US, which thought that all proper preventative measures had been put in place, were woefully unprepared for the pandemic.

And yet excessive preparation for the worst has its downsides, too. Fears of rising global population produced mass sterilisation programmes in many parts of the developing world, some championed by US foundations. The Doomsday Clock (a copyrighted name owned by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists), which measures the notional time until global destruction, was pushed up to seven minutes to midnight in 1962, the year of the Cuban missile crisis, but then re-wound by five minutes the following year. Ferguson is incredulous that in 2018 it was advanced right up to 11:58 on the grounds that “humanity continues to face two simultaneous existential dangers—nuclear war and climate change.” This is based on patterns we want to see, argues the author, rather than on reality. What if we become so worried about doom and disaster that we cede powers to governments to protect us, asks Ferguson, and end up in a totalitarian nightmare? Libertarians might worry the lockdowns have already pushed us well on the way to this gloomy scenario.

All this narrows down the sweet spot, then, of what we should be looking out for: threats that are not exaggerated on the one hand, but are real on the other. Finding a way of thinking that strikes the right balance is not easy, as the book’s conclusion makes clear. Ferguson enumerates a range of possible sources of future disaster, name-checking alien invasion, super-volcanic eruptions, supernova/hypernova gamma-ray bursts and “unfettered cyberwarfare.” He is not enormously convinced or convincing about any of these—although he quotes approvingly the AI thinker Eliezer Yudkowsky’s aphorism that the minimum IQ to destroy the world drops by one point every 18 months.

Ferguson falls back instead on the classic geopolitical foreboding about China and picks up Henry Kissinger’s warning that “we are in the foothills of a cold war.” There is no problem at all, of course, in covering rising tensions between Washington and Beijing and indeed between Beijing and many other parts of the world. How much that has to do with “doom” is another matter: the Cold War coincided with tens of millions of lives being sacrificed in the Soviet Union and in China under Mao. The Cold War itself did not cause disaster. Perhaps it even worked.

And in a funny way, that last thought makes Ferguson’s book less a general history of catastrophe than one of resilience. One of the main takeaways from Doom is that while we are usually braced for disaster, and sometimes have to deal with it directly, we somehow manage to keep going. That, incidentally, is pretty much what Adam Smith said 250 years ago in The Theory of Moral Sentiments. If China and its entire population were “suddenly swallowed up by an earthquake,” Smith wrote, people would be horrified, reflect on the precariousness of life, and worry about what the implications would be for trade. But then they’d get back to their regular routines, going about their business and taking their pleasure “with the same ease and tranquillity, as if no such accident had happened.” For the most part, the human story is about muddling along, come rain, come shine, come pandemic and come whatever else chance, serendipity and misfortune throw at us. It’s almost enough to make one feel optimistic.

Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe by Niall Ferguson (Allen Lane, £25)