In 2016, Donald Trump did not expect to win the US presidential election. The casting of his administration was less sinister masterplan, more frantic improvisation. But this time the preparations are thorough, public and—to many—genuinely frightening. This extends well beyond Trump’s own talk of being his followers’ “retribution” and ruling as “dictator”, if only on day one. At his back, he has the intellectual resources of a host of well-funded thinktanks, who have produced detailed plans. One, Project 2025, lays out ways to “rescue the country from the grip of the radical Left”—partly through policy, but also through transforming the executive branch. The would-be insurrection of 6th January 2021 forced those around Trump to choose whether they were willing to stick around; those who remain are hardcore loyalists. The more mainstream figures who exercised restraint last time are long gone, and unlikely to return.

So there are now real fears, even on his own side, that if Trump wins this time, he will set about establishing an autocracy. The conservative McCain Institute warns of the risk that the US’s “democratic system” could collapse “under the assault of neo-fascist actors”. William Cohen, a former Republican senator, fears that Trump is “a clear and present danger to our democracy”. Three of Trump’s former White House staffers went on TV together to say the same thing. But what exactly is the Trump camp proposing to do? And what steps are his opponents taking to stop them?

Old-school tyrants tended not to worry about legality. That’s why, in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, there are “no longer any laws”. But today’s aspiring Big Brothers take a -subtler approach, finding technically legal means to circumvent restraints and concentrate their power. One prospect that US pro-democracy groups fear is that Trump could seek to deploy the military to crush dissent. As Aziz Huq of the University of Chicago Law School points out, this may jar with US democratic tradition, associated with the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878. But through the 1807 Insurrection Act, it is legally possible.

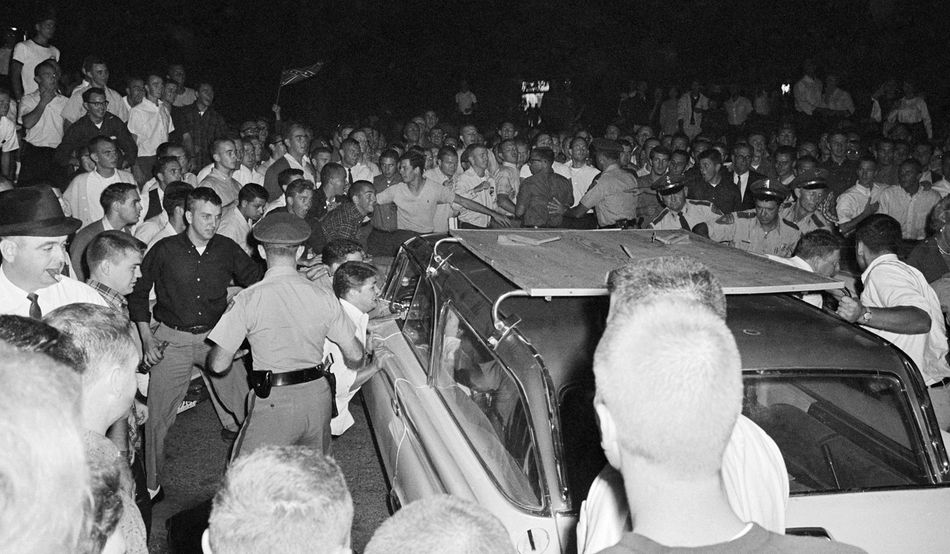

It was under this law that JFK deployed the National Guard to stop violent segregationist attempts to block the integration of universities in Mississippi and Alabama in 1962 and 1963. Thirty years later, George HW Bush used it to authorise sending federal troops to quell riots in Los Angeles. And during the 2020 George Floyd protests in Washington, a furious Trump let aides draft a proclamation invoking the act to allow him to deploy troops.

In Iowa last year, he suggested he would send troops into American cities to fight crime. (In March the Democratic governor of New York, Kathy Hochul, deployed the National Guard in the city’s subway to do just that; they were swiftly forbidden from carrying long guns.) As a former senior Trump administration official told NBC News in January, “The Insurrection Act is a legal order, and if he orders it there will be military officers, especially younger men and women, who will follow that legal order.”

This scenario has won much attention, but it isn’t the only legal means by which the federal government can coerce American citizens. As Huq points out, there are other federal agencies that are not covered by those 19th-century statutes. The armed forces of the federal government at the controversial Waco siege in 1993, for instance, were not from the army or the National Guard, but the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, and the FBI.

This is particularly applicable to another Trump proposal: his plans to round up millions of undocumented migrants, remove them to detention camps, and deport them. This would be done by agents of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which includes both the Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Trump has promised to order “massive portions” of federal law enforcement to focus on immigration. According to a recent report by the anti-authoritarian group Protect Democracy, the DHS’s powers “have proven particularly vulnerable to abuse”. Michael Sozan of the Center for American Progress was chief of staff to Mark Udall (the Democratic senator for Colorado from 2009 to 2015); he is “incredibly concerned” at the idea of an “authoritarian president” giving DHS and other law enforcement agencies “the ability to indiscriminately ask people for their papers, and if they don’t have them… [to] deport them almost on the spot, without due process.”

This may sound like a clear violation of rights, but a key pro-Trump thinktank, the Center for Renewing America, has found an ingenious means to do this in a way it insists is legal. The fledgling USA adopted a series of draconian laws, the Alien and Sedition Acts, which effectively criminalised political opposition. One of these, the Alien Enemies Act from 1798, allowed the federal government to summarily deport citizens of nations with which the US was at war. But how would this help now? The idea is that recognising Mexican drug cartels as enemy states would allow the government to declare war on them, to label Mexicans as “alien enemies”—and so, as news website Axios reported last year, to “quickly remove smugglers and migrant criminals.”

Unlike the DHS, the Department of Justice has been around long enough to develop restraining traditions. But another Trump proposal would undermine this, extending the impact of stronger presidential powers right into the heart of the criminal justice system. In 1973, Richard Nixon fired two attorney generals in one night for refusing to dismiss the special prosecutor who was investigating Watergate. In the wake of this “Saturday Night Massacre”, a convention developed that presidents should not seek to control the department’s investigations. Trump, however, has vowed to appoint a special prosecutor to “go after… the entire Biden crime family.”

During his first administration, top officials from the Department of Justice showed some willingness to maintain the conventions, but there was a striking exception. Jeffrey Clark allegedly attempted to coerce officials to sign a letter which falsely claimed there were issues with the 2020 election results. He was indicted in August by a Georgia grand jury, and pleaded not guilty. If Trump wins, he may put Clark in charge of the justice department, as he almost did in his last weeks in office. Trump proposals also include gutting and reconstructing the FBI on the grounds that it is insolubly biased against conservatives.

Direct White House control of the Department of Justice would allow Trump to pursue what he defined in March 2023 as his mission for government: retribution. In January this year, he named Nikki Haley, then his last remaining rival in the Republican primaries, as another potential target for investigation. He has also talked of deploying the powers of the regulatory agencies to go after his critics, not least in the media. He has pledged to bring the television and internet regulator, the Federal Communications Commission, under his direct authority.

Across the US, officials already face threats of violence

Conversely, Trump plans to weaponise the presidency’s largely unconstrained power to pardon those convicted of federal crimes. Protect Democracy argues that, during his first administration, Trump developed a new concept: what it dubs the “henchmen pardon”. This could be used to “license violence by his allies” and “reward illegal political activity that accrued to his benefit.” Trump has certainly talked about pardoning those jailed for their role in the attack on the Capitol in January 2021. Across the US, officials already face threats of violence; the prospect of politically motivated pardons seems unlikely to improve the situation.

Compared with all this, a final proposal, centred on a new classification called “Schedule F”, sounds reassuringly boring—but it could have far broader consequences. Trump sought to create Schedule F in the last weeks before the 2020 election. He issued an executive order empowering him to reclassify civil service policy advisers as political appointees, thus removing their protections against being fired. Biden reversed this, but Project 2025 would revive it, to allow for a huge purge of what some Republicans call the “deep state”. This would involve firing perhaps 50,000 civil servants and replacing them with Trump loyalists, and Project 2025 has been busy recruiting in readiness. Critics worry this would trigger a haemorrhage of expertise, endangering everything from food safety to national security.

According to a recent report from the public policy research group Democracy Forward, however, this is just the most eye-catching aspect of the proposed purge. It lists a litany of other measures available through federal executive powers, such as weakening labour union protections to ease dismissals, firing “any federal employee who has worked on policies the new administration opposes”, introducing an “ideologically-based civil service test”, targeting disciplinary action based on civil servants’ political views, and removing security clearances.

The urge to purge is driven by conservative frustration at what’s perceived as endemic liberal bias. Some of the measures involved, such as reducing headcount and relocating agencies out of Washington, might be done for perfectly good reasons. But according to Jonathan Swan of the New York Times, “People close to Trump are already drawing up lists of ‘disloyal’ officials in the national security apparatus who will be targeted for retribution.”

These proposals are the fruit of sustained creative thinking and legal scholarship by committed individuals, based in a range of cooperating organisations. In response, something similar is taking shape among those determined to fight back. So if Trump wins, how could these measures be stopped? There is Congress, of course, though the marginalising of anti-Trump Republicans makes that more difficult. In theory, House appropriations committees can block funding for the federal government; the Senate can withhold consent for nominations. There may well also be mass protests, but whether they would be effective is anyone’s guess.

Then there are the courts. As the New Republic has noted, by the end of his presidency, one in four active federal judges was a Trump appointee. Liberals bemoan the conservative super-majority on the Supreme Court. In January, the former president’s lawyer Alina Habba pointedly remarked that the Trump-appointed Brett Kavanaugh would “step up” in her boss’s favour. But the Court has not become supine. It rejected Trump’s claims of election fraud, for instance; it seems to sense that its reputation is at risk. If and when a new Trump administration starts to put America’s whole system of federal government under pressure, it may be that the Court is one of the fracture-points. Michael Sozan argues the need for smart lawyers who are trying to come up with new arguments about how the rule of law must be upheld, why the administrative actions must fall”. He says “networks of lawyers” are coming together, preparing to “hit back”, getting ready to “use the court system in an aggressive, responsible way.” Crucially, these new coalitions stretch across a wide swathe of the political spectrum.

One striking sign of this was an opinion piece published in the New York Times last November by three leading conservative lawyers, George Conway, J Michael Luttig and Barbara Comstock, which lambasted the “growing crowd of grifters, frauds and con men” among conservative Republican lawyers who, they charged, were “willing to subvert the Constitution”. They announced the creation of a new Society for the Rule of Law. This is part of a movement that aims to build “a large body of scholarship to counteract the new orthodoxy of anti-constitutional and anti-democratic law being churned out by the fever swamps.” Luttig is a former court of appeal judge, and has denounced one of his former clerks, John Eastman—another Trump ally among those indicted in Georgia on charges of racketeering linked to the 2020 election. (Eastman pleaded not guilty.)

Trust is slowly, carefully built between already bruised anti-Trump Republicans and people with whom they disagree on everything, except saving democracy

This bid to build wide alliances extends beyond the legal sphere. Aisha Woodward of Protect Democracy, for example, says her organisation “has structured itself in a very specific cross-partisan way, where we have people who worked for Ted Cruz, and people who worked for Elizabeth Warren, all working together not because we agree on climate change or marginal tax rates, but because we are committed to the principle that elections need to be free and fair, that there needs to be a peaceful transfer of power, and that the tools of government should not be weaponised against political opponents or marginalised communities.” More of this is afoot than is publicly visible, as trust is slowly, carefully built between already bruised anti-Trump Republicans and people with whom they disagree on everything, except saving democracy.

But how could those Trumpian plans to concentrate power in the presidency be countered? For Skye Perryman, CEO of Democracy Forward, “It’s important to use every tool in the toolbox that democracy provides.” In an attempt to forestall purges, the Biden administration has begun a new rulemaking proceeding which aims, as Sozan puts it, “to put a huge speed bump in front of Schedule F.”

A speed bump, rather than a roadblock, because the new rule can be undone. Joe Gaeta of Democracy Forward argues that federal agency relocations designed to purge staff would run afoul of best practices outlined by the Government Accountability Office, which conducts investigations for Congress. In a petition that Democracy Forward filed with the Office of Personnel Management, the organisation highlights additional protections for career staff that could be put in place.

If Trump wins, congressional appropriations committees may have a particular interest in reviewing rushed relocation plans that are intended to hollow out, rather than improve, a given agency. And there is a specific Supreme Court ruling that could be used to try to block, or slow, a purge of the CIA.

All this raises an ironic possibility: that the long ascendancy of conservative legal orthodoxy might actually end up providing ways to stymie Trump’s more autocratic plans. The judiciary has been abandoning its deference to federal agencies. This scepticism, one Capitol Hill veteran observes, “might actually be a good thing”, in that, in some circumstances, “when you’ve got an authoritarian coming in and wanting to disregard any checks, the judiciary is a check on that.” Like the emergence of the Society for the Rule of Law, this points to a fissure between small-state conservatives and Trumpist authoritarians which may itself become an obstacle to the concentration of power.

Part of it comes down to exhorting civil servants to be brave

Meanwhile, however, many individual civil servants may be exposed to severe pressures to act against what they see as the public interest. So the means to bolster resistance at this level may be less philosophical. Protect Democracy is recommending that they “evaluate security at the community, household, and personal level”, including “training for the unexpected” and planning in advance to help those who may need it. The Brennan Center for Justice, based at New York University School of Law, advocates measures such as “bystander intervention training” to try to ensure that officials subjected to hostility and abuse are supported.

Part of this comes down to exhorting civil servants to be brave. At a McCain Institute event in Arizona, the conservative Republican Liz Cheney, who lost her seat in Congress over her refusal to toe the Trump line, made a point of praising individuals for their courage in defending their institutions in January 2021. As one person at a pro-democracy group told me:

Some of it is just helping civil servants understand that if the worst-case scenario happens, they’re not going to be alone. There are organisations out there that are preparing for this… and these public servants are going to have resources to turn to, that can help them navigate this uncharted territory. That there are people out there that have their back and are going to be willing not only to defend the principle of a nonpartisan civil service but also to defend individuals who are put in really difficult circumstances.

Conversely, campaigners are preparing to put moral counterpressure on Department of Justice officials who are told to participate in the weaponising of pardons and investigations. As Woodward puts it: “It’s important that the people who are in these positions of power and public trust have a good understanding of what their rights and obligations are, and the potential professional consequences that might exist for them down the line, depending upon the actions they take.” She points out that “former Trump administration lawyers have been barred from practising law or have received sanctions from state bar associations. Those potential real-life consequences could have an impact on the calculus around decisions future officials make.”

Legal scholars are being asked to probe how unconstrained the presidential pardon power really is. And as Aziz Huq notes, “There is case law about the illegality of politically motivated prosecutions.” Likewise, Sozan says that “the first time that a Trump Department of Homeland Security starts to do indiscriminate roundups of people that they suspect are undocumented immigrants”, there will need to be lawyers who have already done the necessary drafting, and “are ready to go at a moment’s notice”. Huq reports that the Brennan Center, for one, is developing arguments to challenge uses of the Alien Enemies Act.

As for the prospect of Trump invoking the Insurrection Act, Richard Blumenthal, a Democratic senator for Connecticut, is working with the Brennan Center to develop legislation that would clarify what counted as “insurrection”, tightening the basis on which the president could order the use of force. But this is a very long shot. Whether or not the military is deployed against protesters may well come down to how individual soldiers respond to an order to suppress dissent. As the constitutional law scholar Amanda Hollis-Brusky told Slate’s Amicus podcast recently, “the only thing we can do is… call it out and hope that good people are willing to disobey. That is the scariest place I can imagine us being.” Campaigners are planning to make sure military personnel understand both their rights and their obligation to resist illegal orders, with all that that implies.

The simplest way of avoiding any of this, of course, is if Trump loses. Groups such as Protect Democracy and Democracy Forward are among those trying to bring the fearful scenarios outlined here to public attention before November. But for Whitney Phillips, who researches right-wing media cultures at the University of Oregon, this is not straightforward, partly because many conservatives see their liberal opponents as evil, believing it is they who are trying to destroy democracy. Communicating effectively requires a much more fundamental examination of who delivers messages, and how they are likely to be received. Warning that Trump is going to usher in tyranny risks simply triggering counter-accusation. Witness Fox News last June labelling Biden a “wannabe dictator” for “having his political rival arrested”, and Trump himself declaring in March that the president is a “danger to democracy”, on the basis that his handling of illegal immigration from Mexico is “a conspiracy to overthrow the United States of America”.

Even if Trump is defeated, the underlying issues will remain. The hard problem is that not all Americans see the death of democracy as a disaster. Some seem actively ready for authoritarianism or, as Phillips suggests, for a kind of apocalyptic showdown—even believing liberals are the apocalypse. And as some liberal pro-democracy activists observe bleakly, plenty of Americans are so disillusioned with what democratic politics has to offer, it’s hard to get them to care.

Addressing that may involve both systemic reform to make government better reflect the will of the majority, and showing that politics really can improve not just the electoral college, but people’s actual lives. The question is whether the US is now so polarised that any of that can happen without a brutal confrontation coming first—on a scale that would make a fundamental rethink unavoidable.