On 17th April 2023, the Moscow City Court sentenced my son Vladimir—Volodya as I call him, or Vlad as he was known to schoolfriends in Harrow and university friends in Cambridge—to 25 years in a maximum-security penal colony. This sentence is not a punishment only for him. His three children will grow fatherless into their teenage years and adulthood: the youngest was 10 when his father was arrested, the two girls 13 and 16. His wife has abandoned her normal life and is tirelessly fighting for her husband’s rescue. His 90-year-old grandmother has lost her eyesight and feels grief beyond words. His father, also a prominent Russian journalist, was already dead by the time of his son’s arrest. As for me, I am surviving.

I survive with the help of a single thought. Since my son was arrested on 11th April 2022, my life has been reduced to the pursuit of one obsessive goal: to see my son alive and free. While it is not certain that Vladimir will remain alive for the whole duration of his sentence—in fact, the chances that he will are slim, given his state of health and conditions in a Russian penal colony—it is safe to say that I will not see the end of his draconian imprisonment in my lifetime. That is why I decided to write this short tribute to my son. May it be both my testament and my declaration of love.

I sometimes ask myself: where does Vladimir’s fearlessness come from? The answer, I think, lies in the accumulated historical experience of Russians and of our family. After all, generations of our ancestors, with their wisdom and humour, their will to live and aspiration to learn, their perseverance against all odds, had little choice but to produce offspring resistant to adverse circumstances. After all, Vladimir himself is a historian.

My husband and I were young and inexperienced parents. When we got married, we were both still undergraduates at the Moscow State University. By the time of the graduation ceremony in 1981 I was heavily pregnant, and two weeks after my son was born, I took my first postgraduate exam. Ours was a typical family of Russian intelligentsia. My son’s four great-grandfathers, born in the 19th century, came from different ethnic backgrounds in what was then known as the Russian Empire—a Russian, a Jew, a Latvian and an Armenian. The mixing of their offspring was only made possible by the social upheavals brought about by the Russian Revolution. In the subsequent years of tumultuous Soviet history, our grandfathers lost all their property. Some of them lost their lives. Their memories and their experience were the only earthly goods that we inherited. My little Volodya was a bright and curious boy; he readily absorbed the impressions made by the world around him.

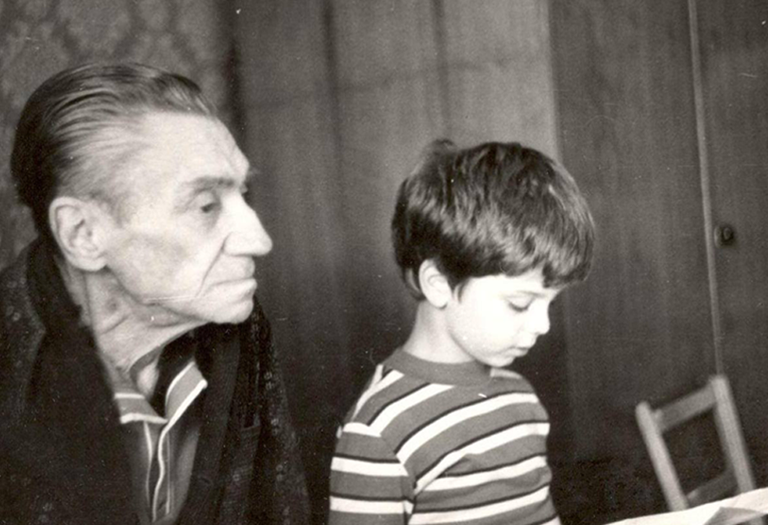

My son was an only child, and so he grew up surrounded by adults, listening to their stories and drawing his own conclusions. His paternal grandfather, Alexey Kara-Murza, told him about the Gulag labour camp in the Russian Far East, where he was taken in a goods wagon in late November 1937. The journey lasted several weeks, and the prisoners had to sleep on bare boards. Their hair froze to the floor; when they woke in the morning, they were unable to lift their heads. Released under the so-called first Beria amnesty just before the war with the Nazis, he worked as a journalist through the whole war, was wounded several times and in May 1945 reached Prague with the Russian Army.

My father, Sergey Gordon, died too young to be able to speak to his grandson. So it fell to me to tell Vladimir about the antisemitic campaign that started in 1949, just as my father finished school and was denied admission to the physics department of the Moscow University for being a Jew. Later, when he became a physicist and took part in pioneering research into laser technologies, he was not allowed to go to international conferences and could only publish his works with a Russian co-author whose name would appear first, contrary to the convention of using alphabetical order.

My mother, Nina Gordon, was a very sociable and optimistic person, although her life had been full of hardship. Her family tried to “forget” their past because her father, who fought in the First World War, had been an officer in the tsarist army. His three St George’s Crosses were exchanged for food in later years, but we still have the diary he kept during the military campaign of 1916. During the Second World War, when German troops were only miles away from the Russian capital, my mother’s family stayed in Moscow. For a year, from 1941 to 1942, Moscow schools remained closed; my mother and her younger sister had to work at a military factory to get ration cards for food. They were too small to reach the top of the machine tool and had to work standing on stools.

My son’s paternal grandmother, Maya Kara-Murza, the only survivor of the old generation, lives in Moscow on her own. She turned 90 this year, and has seen it all before—Russian history repeating itself as if caught in a devil’s circle. At the age of four she saw her father, a former Latvian revolutionary, arrested during Stalin’s purges, allegedly for treason. He was shot, only for his reputation to be posthumously rehabilitated 20 years later.

Maya spent six years in an orphanage for the children of the “enemies of the people” before her mother could find her. Her beloved grandchild’s unthinkable sentence, on a Stalinist scale and on an equally false charge, makes her desperate. She has little time left to wait for his release.

Apart from the immediate family, Vladimir was also surrounded by great-uncles and great-aunts, cousins and friends—historians, sociologists, linguists, mathematicians, doctors, engineers, artists, musicians and even a Jewish programmer turned Orthodox priest. My own generation grew up in what the poet Anna Akhmatova called “vegetarian times”; our parents tried not to pass the fear they had inherited from their own parents on to us. My son was a child in the time of change and hopes for even more of it. The media started talking about painful events from the Russian past: collectivisation, organised hunger, denunciations, arrests and executions, persecution of entire ethnic groups, lawlessness and corruption. My inquisitive and perceptive Vladimir couldn’t help but notice that fragments of our family history tallied with the avalanche of information about Russia’s past that hit us all in the late 1980s. He put two and two together—it all made sense.

Three days in 1991 shook our world. The attempted coup that began on 19th August, during which Soviet hardliners tried to seize power from Mikhail Gorbachev, kept us glued to television while Vladimir’s dad was at the barricades defending our would-be freedom. I worked at a publishing house that had its office on Tverskaya (which until a year earlier was Gorky Street), and from our balcony on the 7th floor we watched heavy tanks heading for the Kremlin in an almost silent Moscow, and the same tanks leaving the city to the applause of the jubilant citizens two days later. We joined the crowd that filled the street after the tanks were gone, and for the first time in my life I could breathe the air of freedom in the country where I was born. It seemed that the “velvet revolution” was happening in front of our eyes. As we see now, 30 years later, others have taken advantage of its victory.

In August 1991 Vladimir was just two weeks short of his 10th birthday. He vividly remembers those events and always says that it was a turning point in his life. The years after—his second decade—formed him as a political being. In the early 1990s my husband, Vladimir Kara-Murza Senior, joined the first Russian independent TV channel. His daily analytical programme, Today at Midnight, became a must-see in our family. Of course, it was on too late for an 11-year-old, but who could have stopped Vladimir? He could already name many members of the Russian government and parliament. Some of them, thanks to his father, he had met personally. Yegor Gaidar, acting prime minister and the author of short-lived Russian economic reforms, and Boris Nemtsov, the deputy prime minister who once was hailed as a possible future president, were his idols.

Little Vladimir was a fountain of creative energy. He made up stories from his earliest childhood and began writing and illustrating them as soon as he learned the letters. Later, when he mastered the typewriter, he churned out his stories at an amazing speed, letting the pages fly around our flat. They were short—no more than a page each—stylistically daring and absurdly funny. I collected and published them in a small booklet—to this day I keep a few of the 100 copies I printed of this bibliographic rarity. We staged plays written by Vladimir and played impersonation games. He could brilliantly imitate the voices and gestures of politicians; at family gatherings we would laugh ourselves nearly under the table, so sharp was his sense of ridicule. I often think that I might have been much happier had my son become a writer, an actor or a musician—he played the clarinet into his early twenties and reached a professional level. But this is just a mother’s egoism.

Russia was in turmoil in the 1990s. Political parties sprang up like mushrooms after rain. When he was 12 years old, Vladimir decided to create his own party whose goal was to defend the rights of children. He single-handedly wrote the programme and the charter, designed the membership card and the party stamp and relentlessly recruited new members among his peers and adults (there was no age limit for joining). He was so adamant that he even persuaded his father to go to the Ministry of Justice to have his party registered. Despite all his efforts, the Russian bureaucracy remained indifferent to the needs of the new generation, and the Children’s Democratic Party of Russia never came into existence.

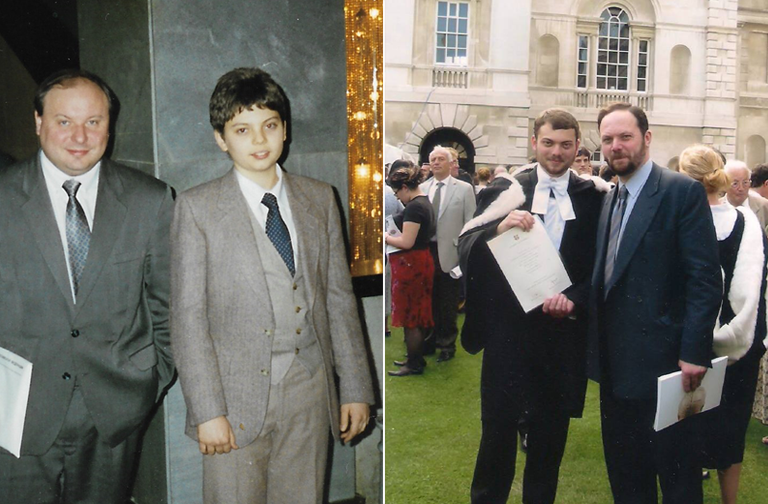

Vladimir’s adolescence began with a great change in our personal lives. His father and I parted—though we remained friends until his untimely death—and at the age of 14, my son left Russia with me and my new English husband to settle in the London borough of Harrow. It was a cultural shock for both of us, but more difficult for him. He was immediately thrown into a classroom of teenage boys, which is not necessarily the friendliest milieu for someone from a very different background. At first “Vlad” was seen with apprehension, teased and mocked by his fellow students. He had to prove he was worth their friendship and respect, and he did. He became an equal member of the school community and later one of its leaders. As far as I know, he is still in touch with his classmates.

We witnessed our first UK general election in Harrow. On the 1st May 1997, aged 15, Vladimir sat as an observer at the polling station and stayed up all night to follow the results. Politics had become his private passion, and he would study the intricacies of political structures, the backstage tools of diplomacy and the mechanisms of domestic politics. He wanted to know how a functional democracy worked. His fondest wish was—and still is—to bring this democracy to his native land.

I am not going to write here about Vladimir’s academic achievements, of which I am unashamedly proud. While still at school he started working as a freelance journalist, first sending reports from London to Russia (the editor did not know he was just 16) and then making regular contributions to the Russian London Courier. He did well at university—one of the third, if not fourth, generation of his family to become a historian. As an undergraduate, he was already practically independent. He would come home for holidays, sleep well into the afternoon, and then rush off to political forums, conferences and meetings. He amazed me with his knowledge of history, both Russian and British.

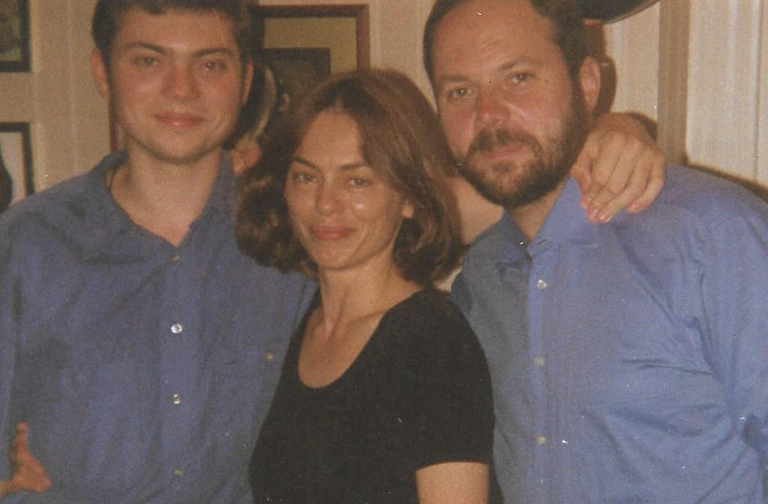

It was in England that Vlad grew close to two men who shaped not so much his political views—which were already quite clear—as his intransigence in defending them. The first was Boris Nemtsov, by then one of the leaders of the Russian opposition and an outspoken critic of the regime until his assassination in 2015. The second was Vladimir Bukovsky, a legendary Russian dissident-in-exile who in 1976 had been exchanged for the leader of the Chilean Communist party. (To this day, my son firmly believes that either of these two men would have been a worthy president of Russia.) And it was in England that Vlad perfected his humour that supports him and all those who love him in this darkest hour.

After Vladimir graduated, I considered my duty as a mother fulfilled—I had brought him up as best I could. The rest is history. Information about my son’s journalistic, political and public activities is readily available. I myself often learn it from the media.

In the 20 years that followed, I watched my son’s career with a mixture of admiration and growing concern. Vladimir stood for election to the Russian parliament in December 2003—he was the youngest candidate and the only one to be supported by both independent democratic parties, the Union of Right Forces and the social-liberal Yabloko. Despite a less-than-clean election campaign, Vladimir, with his 22 years and no personal fortune, came in second, ahead of the Communist party candidate. (Predictably, he lost to the candidate of the ruling party United Russia who, by a strange coincidence, also happened to be the owner of the Seventh Continent luxury grocery chain.)

Next, he established himself as a journalist in the United States, both on television and in print media. For eight successful years, he worked at a new, independent Russian-language TV channel, travelling to Washington to set up a new bureau, before the whole operation was bought in 2012 by an obscure new owner—a deal that coincided with Putin’s return to the Russian presidency after a brief “liberal respite” under President Medvedev. The new owner insisted that Vladimir resign as the Washington bureau chief.

Then, in 2015, we learned from a late-night phone call that Vladimir had been poisoned in Moscow. I was on holiday in America at the time, enjoying the company of my young grandchildren. My daughter-in-law immediately flew to Russia, while I stayed with three frightened kids, the youngest only three years old, from whom I had to hide my anguish and despair. We spent the next days waiting in extreme anxiety, sleeping together in the same bed at night, dreading news of Vladimir’s condition. When I managed to get to Moscow a week later, I saw my son lying in a coma, entangled in the tubes of life-support machines. He looked like an octopus. It was almost like seeing the corpse of my own child. I wouldn’t wish that on any mother in the world.

Against all odds, Vladimir survived that first poisoning, as well as a second in 2017. But my world had been shaken, never to recover. For the last eight years I have been living as if under the sword of Damocles. Its latest stroke has coincided with a catastrophe on a much larger scale—an unprovoked aggression against an independent European state. I am sometimes asked how I feel. It is difficult to describe in words, especially to people with no personal experience of such suffering—but let me try: I live in an emotional hell, grasping at straws of hope. I pray every day to see my son free. I also pray every day for this nightmare of a war to end—but it goes on.

On 31st July 2023, the First Moscow Court of Appeal left the sentence of 25 years imprisonment to Vladimir Kara-Murza unchanged. From that day it entered into legal force. Then, on 4th September, I learned that he had been secretly moved out of the detention centre in Moscow and has disappeared from view.

![Vladimir at his Court of Appeal case on 31st July this year. XXXXXX. Image: Darya Kornilova [TO CHECK]](https://media.prospectmagazine.co.uk/prod/images/gm_preview/2f812aa11201-vladimir03.png)