Ever since ancient Rome, the sea, seabed and seashore have been accepted as part of the commons—res communes omnium—belonging to everybody equally, and inalienable as state or private property. The commons as a distinct form of property was taken forward in Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest of 1217, the twin bedrocks of common law and all democracies.

A commons depends on the “sovereign”—in the UK’s case, the monarchy—acting as steward or trustee, with responsibility for preserving it for generations to come. For more than 650 years, following a ruling by King Edward I in 1299, the monarchy accepted this positive duty, known as the Public Trust Doctrine.

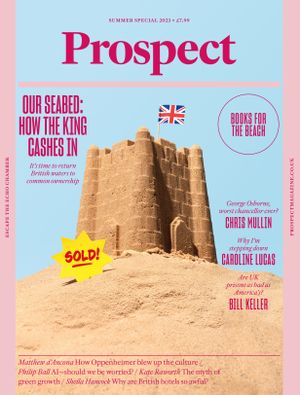

However, in the past 60 years, the monarchy has gradually plundered the blue commons—the seabed around the British Isles—transforming it into nothing less than a rentier capitalist empire. That empire, in the decade since 2013, is thought to have earned the royal family in the region of £193m. The new king, Charles III, who while heir to the throne established a reputation as an environment protector, has inherited and continues to profit from this system.

The evolution began in 1961, two years after the discovery in Dutch waters of large quantities of North Sea gas. The Crown Estate was constituted by an act of parliament to manage the assets belonging to the monarchy, with a mandate to maximise revenue and capital value for the Treasury. As King, Charles is not involved in managing these assets; they are not the monarch’s personal property but “the sovereign’s public estate”, managed by the Crown Estate supposedly in the public interest.

At the time, the Crown had no ownership rights in the sea beyond the lower-tide mark on the seashore. Indeed, in 1951 the Labour foreign secretary, Herbert Morrison, had declared that the sea around Britain was not the property of the state or anybody.

But in 1962, as was revealed much later, the Queen privately told the first commissioner of the Estate—the leader of the board running the corporation’s commercial interests—that she had seen something about “taking over rights on land under the sea”. In fact, the Estate’s legal adviser in 1959 had proposed enshrining in law the extension of Crown lands to the whole of the continental shelf. Other Estate officials advised against trying to extend rights to the seabed, because this would draw attention to the fact that no existing legislation gave such ownership.

However, prompted by the passing of a UN convention that granted states rights to the continental shelves by their shores, and by drilling companies seeking legal clarity on ownership of the seabed in expectation of finding commercial oil and gas reserves, the outgoing Conservative government of Alec Douglas-Home passed the Continental Shelf Act in 1964. It gave the Crown Estate precisely the rights it had earlier refrained from seeking. This granting of ownership to the Crown Estate was a huge enclosure of the commons but did not change the fact that the seabed was still part of the commons. The Crown, and the government as its agent, became the seabed’s steward, responsible for preserving it.

As a business, the Crown Estate grew at a modest rate during the following decades, returning all revenue to the Treasury while the monarch received a fixed sum—the annual “civil list”—to pay for royal expenses. The Estate’s marine activities did not include the North Sea oil and gas bonanza, for although the Crown owns the oil and gas found beneath the sea, as beneath the land, their exploitation is managed by the government and its agencies.

In the 1980s, the Thatcher government sold leases on lots in the North Sea to oil companies at ridiculously low prices, taking the revenue as a windfall profit to pay for tax cuts. This was a blatant depletion of the commons, in sharp contrast to Norway’s decision to use its surplus oil and gas revenues to create what is now a mammoth sovereign wealth fund, ensuring benefits flow to both current and future generations.

The next phase came in 2001, when offshore wind energy took off. In a first step, the Crown Estate leased 12 seabed sites of 10 square km each. Three additional rounds saw leases awarded in 2003, 2010 and finally in 2021, when the Crown Estate auctioned six large lots, most of which went to German and French firms. The most recent round included the novel addition that the companies would pay the Crown a ground rent, an annual “option fee”, even before producing any wind energy. It was estimated that this round alone could generate nearly £9bn over 10 years.

And here is the rub. Over the past two decades, successive governments have allowed the Crown Estate to become a monopolistic corporate enterprise. In 2004, the New Labour government passed the Energy Act, which enabled the Estate to claim a share of the revenue from production of all offshore wind and wave electricity. In 2008, it extended this to gas and carbon dioxide storage.

These measures intensified a clear conflict of interest for the Crown Estate between being a steward responsible for preserving the commons for future generations and a business working to maximise revenue and profits. Meanwhile, to add to its profits, the Estate had started to invest in joint ventures.

In 2010, the Parliamentary Treasury Committee concluded that the Crown Estate was focusing too much on income from its control of the seabed and seashore, rather than on the long-term public interest. In what was hardly an adequate rebuttal, the Estate’s CEO said he was pleased the committee recognised they were running a successful business operation, adding only that the Estate took its responsibility to act in the wider public interest “very seriously”.

Nothing was done to prioritise once again the role of the Crown as protector and steward. The situation was tilted further in favour of commercial criteria in 2012, when George Osborne, at the time chancellor of the exchequer, abolished the civil list in favour of a “sovereign grant”, calculated as 15 per cent of the Crown Estate’s profit. That figure was increased to 25 per cent in 2017, ostensibly to cover the estimated cost of refurbishing Buckingham Palace; at present it is set to revert to 15 per cent in 2028. The creation of a deadline in itself created a new moral hazard, giving the Crown Estate an incentive to maximise short-term profits.

In brief, the Crown Estate has become a monopolistic sealord. It has monopolised offshore wind and wave energy and created an oligopoly consisting of a few, overwhelmingly foreign-owned multinationals, a structure that promises to keep prices and revenues above what would arise in a competitive market. Although the Estate uses an auction process to decide which firms secure the leases, it still decides how many leases to sell, as well as the size and location of the lots.

In the decade since 2013, the Crown Estate has made more than £1bn profit from its marine business (known in the Estate’s accounts as energy, minerals and infrastructure until 2019/20, and inclusive of aquaculture until 2016/17). Over the years, this sum has been delivered to the Treasury, and has contributed to the pot from which the sovereign grant is calculated. Precise figures are difficult to discern due to the opaque nature of Crown Estate accounts, but Prospect research suggests that in the ten years to 2022/23, the seabed has earned the royals approximately £193m.

£193m: the royal family’s estimated earnings from the sea, 2013 to 2023

This sum takes into account King Charles’ magnanimous announcement in January 2023 that the Crown Estate would hand over to the government what a spokesperson called the “offshore energy windfall” from the 2021 round of sales, which boosted the marine sector’s profits from £127.5m to £370.8m in a year. In any case, revenue from the commons should not be treated as a “windfall” at all. It should never have been the Crown’s to begin with.

In its eagerness to make profits, the Crown Estate has even sold development rights for one patch of seabed to two different projects at the same time, one for a giant Danish-owned offshore windfarm, the other for storing carbon dioxide under the seabed. An industry insider commented tersely that the Crown Estate was being “a bit greedy”.

By the financial year ending in 2023, the value of the Crown Estate’s marine businesses was £5.7bn, up by 14 per cent on the year before, mainly because of offshore wind. The Crown is not liable to pay tax on the sovereign grant. Overall, the Estate’s portfolio is worth almost £16bn. It is a major industrial enterprise, but one that does not have to adhere to free market principles, let alone be answerable to the commoners.

The Welsh should feel particularly aggrieved, in that whereas all management and revenue of the Crown Estate in Scotland is in the hands of the Scottish government, revenue generated in Wales is not devolved. Extraordinarily, the value of the Crown Estate’s marine portfolio in Wales rose from £49m in 2020 to £549m in 2021 and to £603m in 2022. None of it went to the Welsh government, let alone to Welsh commoners. No wonder a majority of Welsh people want the Estate to be devolved as it is in Scotland.

25 per cent: proportion of the Crown Estate’s profit given to the royal family through the sovereign grant

These inequities are compounded by the fact that the Crown Estate has not always, before granting leases, carried out environmental impact assessments in accordance with either international law or the precautionary principle, which requires decision-makers to err on the side of caution when considering projects that might entail serious or unknown ecological risks. For the first three rounds of sale of seabed rights, the Estate was required under EU law to demonstrate that it had considered alternative sites before deciding where to locate infrastructure developments such as windfarms. There is no evidence that it did this. Instead, assessments of the environmental impacts were left to developers, with the UK government judging in which sprawling zones development could occur. And the Estate itself has admitted that in the three earlier leasing rounds it didn’t have data with which to make objective assessments.

There has been progress: the Crown Estate and the government will in future examine the environmental impact of offshore windfarms, and outside of leasing rounds, work is under way to better understand the impact on nature of marine infrastructure. Had the Crown acted as the steward of the commons, this work would have been started much earlier.

In one case, the Danish power company Ørsted received approval for a project off the North Yorkshire coast which will affect a Special Protection Area that is home to Britain’s biggest colony of seabirds. The Estate and the government accepted that the project would threaten endangered birds, but let it go ahead on the basis of a promise by the company to introduce an offset breeding scheme to make up for bird deaths. There is no evidence that the scheme will work.

But while wind energy—sorely needed for the green transition—has received public scrutiny for its impact from nature, it is far from being the Crown Estate’s only source of profit from the sea.

Sand and gravel are easily the most mined minerals in the world, with about 50bn tonnes excavated from rivers, lakes and the sea annually. This figure is growing by around 5 per cent each year, feeding demands, led by China, for concrete and other construction materials. There is an impending global shortage, and excessive excavation is already causing land erosion worldwide.

The Crown Estate is the only body in the UK with the designated or presumed authority to oversee the production and sale of our sea sand. It has been quietly expanding mining, to the point where 21m tonnes of sand were excavated in 2022. A quarter was exported, mainly to Belgium and the Netherlands.

The manager of the Crown Estate’s “marine minerals portfolio” said in September 2022 that the Estate works “in partnership with industry, to help support the sustainable use of sand and gravel resources”. If it were a proper steward of the commons, the Estate would also work with conservation bodies, not just those interested in maximising extraction and profits. To protect against erosion and to avoid destruction of underwater ecosystems, there should be regular impact assessments of sand excavation before any more mining begins, done by independent bodies not answerable to the Crown Estate.

Bearing in mind that sea sand is an exhaustible common resource that will become more expensive as it becomes scarcer, a responsible steward would invest all or part of the revenues to maintain the capital value for the benefit of future generations, according to what is known as the Hartwick Rule of Intergenerational Equity. Instead, the Crown Estate is effectively treating all revenue from the sale of sea sand (as well as potash and other minerals found in the sea) as “windfall profit” for current spending.

Another seemingly innocuous activity being encouraged by the Estate is seaweed farming. Seaweed and seagrass are valuable for the marine ecosystem, not least as habitats and carbon sinks (they are far more effective than woodland in absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere). Nearly 90 per cent of seagrass has vanished from UK coastlines—much as a result of pollution, dredging and trawling—since the Estate took over the seabed as its income-earning property. Meanwhile, scientists predict that most of the UK’s 26,000 square miles of kelp forests will be lost by 2100.

£9bn: predicted windfall, over ten years, from 2023 offshore wind leases

Sadly, the Crown Estate has impeded some plans by civil society groups to replant thousands of acres of seagrass by charging, in at least one case, £500 an acre for doing so. One kelp farm company abandoned plans to develop a network of 58 farms around the seabed due to lengthy bureaucratic delays by the Crown Estate. These are not the actions of a benign steward of the commons.

Then there are around 750 aquaculture sites—for farming fish (mostly salmon), shellfish and crustaceans—from which the Crown Estate Scotland (CES), an independent body that gives its entire revenue to the Scottish government, earns a hefty sum. The CES, which takes 1.5 per cent of turnover income, must be partially answerable for fish farming’s shocking record in Britain: farmed salmon have a premature mortality rate as high as 24 per cent from disease and lice infestations; mass escapes threaten wild fish species; and the corporations, most foreign-owned, pay only half the true costs of production, with the remainder, including environmental costs, borne by local communities.

Scottish fisheries complain that licensed fish farms discharge sea lice and pesticides into the sea, killing wild fish. The CES, although more accountable to Scottish ministers, ignores the precautionary principle, and allows seabed dredging for scallops and bottom trawling for prawns, both of which do massive harm to marine ecosystems.

If the CES behaved as a real steward of the commons, it would demand that salmon farmers met higher ecological standards. If it cannot fulfil its positive duty to protect the commons then it should not be steward at all.

So what should be the political agenda? In the long run, a progressive government should want to restore the sea and seabed as part of Britain’s commons. In the immediate term, it should reform the governance of the Crown Estate, insisting that its primary responsibility is to preserve and enhance the capital value of the common resources in the sea around Britain.

The Crown Estate could charge firms more rent for ecologically damaging fish and shellfish farms. By contrast, it should not be charging anything for activities such as seaweed farming or seagrass replanting that revive marine ecosystems. It should make a commitment consistent with the High Seas Treaty, agreed at the UN marine biodiversity conference last year, to rewild 30 per cent of the seabed under its stewardship by 2030. It should stop the export of our sea sand. Above all, the next government should appoint a cabinet-level minister of the sea, whose responsibilities should include overseeing all the marine-related activities of the Crown Estate.

Finally, there is a transformational opportunity for a new progressive government. The King has said the £1bn a year “windfall” from the latest auction of our seabed should go to the public. The only equitable way to treat revenue from the commons would be to recycle it equally to all commoners—that is, to all of us. That £1bn a year should go into a Commons Capital Fund from which common dividends could be paid to every citizen. After all, the Crown’s role was to protect, not to plunder the commons. Charles III inherited an empire at sea—but he has the chance now to change it for the better.