On an afternoon in December, the people of Zebqine prepared to bury another of their sons. Ali Musa Barakat, a Hezbollah fighter, had been killed the day before in cross-border clashes between the Lebanese paramilitary group and the Israeli army. Overnight, a giant picture of him had been set up in the main square, flanked on each side by Hezbollah’s signature yellow flags. A sound system blasted latmiyat, songs of mourning venerated by Shia Muslims.

Ali wasn’t Zebqine’s first to fall, nor was this the first time southern Lebanon had tasted war. Faded pictures of men killed in prior iterations of this decades-long conflict lined the winding street leading to the village, which is a mere seven kilometres from the border. Israel’s repeated invasions of Lebanon gave birth to Hezbollah in the 1980s and have ensured a steady stream of recruits since. Before Ali, his two brothers had died fighting for the “Islamic resistance”, as Hezbollah is known here. Mohammad, the youngest, was killed fighting in 2006 when Israel last invaded Lebanon, the ensuing war reducing southern villages like Zebqine to ruins.

Seventeen years on, there was a sense that history was about to repeat itself, stoking both fear and defiance. “They can never defeat us,” said Ali’s mother, Mona Khalil. Her features remained stern, for expressions of grief were frowned upon in this community, where such deaths—seen as martyrdom—are expected to evoke pride. Around her shoulders, she wore a yellow scarf emblazoned with Hezbollah’s logo—a green-coloured fist pumping a machine gun towards the sky. “We are Hezbollah until our last breath, and Israel knows the meaning of these words,” she said. In her hands, she clutched an A4-sized piece of paper with pictures of her three slain sons.

Since 7th October, Lebanon has been inching closer to all-out war. Hezbollah reopened this long-simmering front hours after its ally Hamas attacked Israel. In a carefully calibrated message, militants fired a barrage of rockets towards the Shebaa farms, a disputed border area that Israel occupies. The operation was intended to show “solidarity with Palestine”, the group said, and set in motion a vicious cycle of tit-for-tat attacks that risks unravelling into full-blown conflict. Hezbollah has used drones and missiles to target Israeli border posts, killing at least 12 Israeli soldiers. In turn, Israel’s air strikes and tank fire have felled around 150 Hezbollah fighters, a figure that is rapidly approaching the group’s reported death toll of 250 from the 2006 war.

Funerals have become a daily routine across southern Lebanon. As the sun set over the hills surrounding Zebqine, mourners gathered for the military-style procession. The men stood to the right. Some wore green fatigues, others white medical bandages that hinted at close calls with death. To the left, women veiled in black fought back tears as they watched uniformed pallbearers carry Ali’s coffin, draped in a yellow Hezbollah flag, down the red-carpeted aisle, and place it on an altar decorated with yellow and white plastic flowers.

Turban-clad imams stepped to the front and led the crowd in prayer. “When one martyr falls, many others prepare to follow,” Ali Yassin, a grey-bearded imam told me. “The martyrdom of one gives morale and strength to the others.” The procession carried the body up the hill to the cemetery, which offered sweeping views of the border area. Israel lay just behind the ridge to the south. Young boys, some wearing fatigues, stood facing the horizon, raising Hezbollah’s flag and beating their chest to the rhythm of latmiyat. You could not help but think they were the next generation of “martyrs” in waiting.

As frustration accumulates along with the death toll, observers are left to wonder—what is the red line that will draw Hezbollah, and Lebanon, into all-out war?

In line with unwritten rules of engagement that had sustained a fragile détente since 2006, most of the initial exchanges of fire hit military targets within five kilometres of the UN-delineated border. But Israel has gradually turned up the dial, pounding targets deeper inside Lebanese territory. Israeli strikes have killed more than 20 Lebanese civilians, including three journalists, in what human rights groups and the UN say could constitute war crimes (Hezbollah’s projectiles have killed six Israeli civilians). In another sign of incremental escalation, Israel has begun striking funerals similar to the one that I attended in Zebqine, despite UN peacekeepers sending times and coordinates to the Israelis precisely to avoid such incidents.

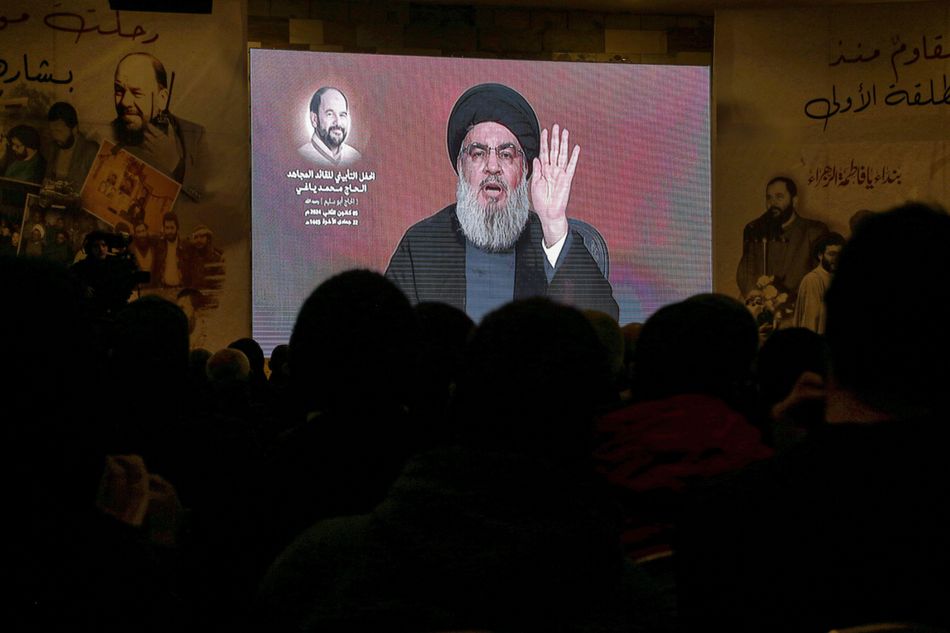

The most daring attack yet came on 2nd January, when Israel brought the war to Beirut with a strike that targeted Hamas’s deputy leader. Saleh al-Arouri was killed alongside two commanders and four others while attending a meeting in Lebanon’s capital, where Hamas has long maintained a foothold. Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s leader, promised revenge. In a televised address, he called the assassinations a “flagrant Israeli aggression on Beirut” and pledged that if the “enemy launches a war on Lebanon, our fighting will be without ceilings or boundaries or rules.” Within days, Hezbollah unleashed a salvo of 62 missiles at the Mount Meron air traffic control base.

But Nasrallah stopped short of declaring war himself. His timid response appeared to reaffirm Hezbollah’s desire to avoid all-out war. That position is constantly tested, most recently after Israel killed senior Hezbollah commander -Wissam al-Taweel, a painful blow that once again signalled a widening of operations. As Nasrallah had laid out in earlier speeches, the operations on the southern front were aimed at aiding Hamas by forcing the Israeli army to operate on multiple fronts. The main onus of fighting Israel, he hinted back in November, rested on Hamas’s shoulders.

There is consensus across Lebanon that the country cannot afford such a war

A conflagration on this frontier would have devastating consequences. Hezbollah is the most formidable militant group in the so-called axis of resistance, a loose alliance of state and non-state actors that also includes Iran and Hamas. Some even see it as taking the lead after the US assassinated Qasem Suleimani, the charismatic Iranian general who spearheaded Tehran’s efforts to grow the network. Hezbollah possesses a vast arsenal of missiles, most supplied by Iran, which it says can reach anywhere in Israel. A fallout here would not just spell destruction for Lebanon and Israel, but further draw in regional allies in Syria, Iraq and Yemen, who have already carried out dozens of low-level attacks on American and Israeli targets as well as ships in the Red Sea.

There is consensus across Lebanon’s otherwise divided society that the country cannot afford such a war. The population is still reeling from a crippling financial crisis that began in 2019, with eight out of 10 Lebanese now living in poverty. The currency and the state have all but collapsed. Public servants hardly report for duty because they must work second jobs to feed their families. State electricity flickers on for a couple of hours a day, if at all. Lebanon’s squabbling political elites have failed to respond or form a new government following the May 2022 parliamentary election, plunging the country into an unprecedented governance vacuum. For 15 months, Lebanon has been without a head of state and without a cabinet.

These twin crises, political and economic, have factored into Hezbollah’s calculations and partly explain its restraint. Lebanese officials thus believe it is Israel, not Hezbollah, who is trying to drag the country into full-scale war, suspicions fanned by the increasingly bellicose language emanating from Tel Aviv.

Israeli officials have repeatedly threatened to invade Lebanon unless it implements a 2006 UN resolution that calls for Hezbollah to remove its weapons between the UN-delineated border and the Litani river, thus creating a roughly 30km buffer zone. Late last year, war cabinet member Benny Gantz told reporters that the situation on Israel’s northern border, where 80,000 civilians have been forced to evacuate, needed to change. “If the world and the government of Lebanon don’t act to stop the fire toward northern communities and to push Hezbollah away from the border, the [Israeli army] will do that.”

Similar threats were made ahead of the 2006 war, when Israeli officials vowed to destroy Hezbollah after it killed three Israeli soldiers and captured two others in a cross-border raid. But the army failed to achieve its stated military objectives, just as it has, so far, in the onslaught on Gaza. During 34 days of fighting, it was Lebanon who paid the price. Some 1,200 civilians were killed and 30,000 homes destroyed or damaged in what became known as the Dahiya doctrine, named after Hezbollah’s Beirut stronghold that was levelled to the ground in a ferocious bombing campaign aimed at shattering the group’s support base.

Hezbollah, however, emerged stronger in the years after, entrenching itself in Lebanese society and politics. In places like Zebqine, demands for its removal are met with mockery. “They [Netanyahu and the United Nations] need to stop messing around trying to bring a state here,” Mona, the mother of the killed fighter, told me. “We have a state that is from us and within us.” Hezbollah may be designated by the UK as a “terrorist organisation” committed to “seiz[ing] all Palestinian territories and Jerusalem from Israel,” but the group is seen by many Lebanese Shia as a legitimate domestic actor and the country’s main defence against Israel’s repeated violations of its sovereignty.

The view is not shared in every corner of Lebanese society, however, which consists of no less than 18 officially recognised religious groups.

In the Christian village of Marjaayoun I met a group of residents and local officials who agreed to vent their concerns if their names weren’t mentioned. More than half of Marjaayoun’s population had already fled in fear that fighting would soon engulf their homes. We sat alone in a restaurant with big glass windows overlooking the valley, a grandstand for the daily spectacle of cross-border fire. Israel’s border wall and surveillance towers could be seen in the distance. Every few minutes, the sound of shelling thundered through the valley. It was here that Hezbollah launched its first rockets towards the Shebaa farms on 8th October.

“What we are worried about is that they [Hezbollah] will use our homes, our hospitals, our lands to fire rockets,” said one father-of-two. His right arm rested around the shoulders of his 11-year-old son, who had come along as school has been suspended since October. “If they come close to my house, I’ll shoot them,” the father said. The men went on to describe how, soon after hostilities began, villagers had set up roadblocks to prevent militants from reaching the village. It was a symbolic gesture to make their position known, for nobody could face Hezbollah. “We are weak because we didn’t resist the same way Hezbollah did,” said one man. Their roadblocks were quickly removed by the Lebanese army. “The Lebanese army is not protecting us. They stand with Hezbollah because they have no choice,” said the father-of-two. “Nobody is able to stand against them.”

To calm the waters, a meeting was convened between Hezbollah and local authorities. “Hezbollah wanted to understand what our plans were, if we would go against them,” said the father-of-two. Wary of igniting internal strife, the para-militaries acquiesced to the community’s demands, promising, at least for now, to keep Marjaayoun free of its weapons. “It was a positive meeting. They told us that they were at our service,” said a local official who was in attendance. Obtaining such assurances has proven more difficult in villages closer to the border, he said. “There, Hezbollah doesn’t listen to anyone.”

Since October, Hezbollah has, for the first time since Israel withdrew in 2000, allowed Palestinian factions such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad to use Lebanese territory as a staging ground for operations

But the rifts go deeper, and further back in history. What has peeved the Christians of Marjaayoun most is that since October, Hezbollah has, for the first time since Israel withdrew in 2000, allowed Palestinian factions such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad to once again use Lebanese territory as a staging ground for operations of their own. “There’s some sympathy for Hezbollah because they are Lebanese,” the local official said. “What we don’t want is a repeat of 1975, when Palestinians came here to use this land for attacks.”

He was referring to a time when Lebanon, and West Beirut in particular, served as the main base for the Palestinian Liberation Organization. This prompted Israel to invade Lebanon in 1978 and again in 1982. Christian militias joined hands with Israeli forces to root out the Palestinians, committing brutal massacres of Palestinian civilians and Lebanese Shia. The balance of power in the country has since shifted in favour of the Shia, but that infamous alliance hasn’t been forgotten. A Lebanese official told me that some Shia eye the Christians’ careful rebuke of Hezbollah as a nod towards Israel.

As a solution, many residents of Marjaayoun, like other Lebanese who oppose Hezbollah, would prefer the Lebanese army to share responsibility for security with UN peacekeepers, in line with the 2006 resolution that demanded Hezbollah cease operating south of the Litani river. In recent weeks, western diplomats have pushed Lebanon’s caretaker government to implement the resolution, seeing it as the only way to stop the conflict from spiralling out of control, even though the resumption of skirmishes has laid bare its limitations.

The coastal road leading to the peacekeeping mission’s headquarters in the border town of Naqoura is lined with lush banana fields, a picturesque scene that belies its perilous potential. Hezbollah is said to use vegetation surrounding the UN base to launch guerrilla-style attacks, with peacekeepers sometimes caught in the crosshairs of Israel’s retaliation. They have been hit a dozen times since the latest round of fighting began. In December, an Israeli tank fired directly at a UN watchtower, setting it ablaze and fuelling suspicion that the strike may have been intentional. Miraculously, no one was hurt. An Israeli army spokesperson claimed they didn’t aim at the UN. (The results of a UN investigation have yet to be made public.)

In spite of the dicey climate, the UN dispatches daily patrols of white armoured vehicles bearing its light-blue flag throughout southern Lebanon to try to keep a lid on fighting. “This is a counter-rocket launching operation,” Captain Fahmi Maswan of the Malaysian battalion told me as we embarked on one such patrol. The aim, he explained, was to detect weapons that might be used to attack Israel. Removing them, however, was the army’s job. “Actually, we only report. The action is taken by the Lebanese army,” he said. At an intersection, the peacekeepers met up with a small contingent of Lebanese soldiers. The young Lebanese officer nodded along as Maswan explained the route. Then the three-vehicle convoy set off, meandering its way through villages.

In addition to direct Israeli fire, peacekeepers have faced hostilities from disgruntled Lebanese, some of whom see the UN as an incarnation of western support for Israel and its failure to stop the industrial-scale slaughter of Gazans. “Free Palestine! Fuck Israel,” a boy yelled in English towards our convoy when it stopped in the middle of a town. In December, a civilian mob of around 20 people threw stones at a UN vehicle. The broken glass injured an Indonesian peacekeeper.

For most of the patrol, the convoy stuck to main roads. The Lebanese soldiers in the back of the leading truck appeared bored. Since the collapse of Lebanon’s currency, they’ve earned less than $100 each month and possess neither the morale nor political leadership to challenge Hezbollah. After an hour of driving around and having found no weapons, the soldiers took a group picture and returned to base.

Naqoura’s main drag was largely deserted. A couple of stray dogs chased the occasional UN vehicle as it passed by. Few inhabitants were left to keep local businesses afloat, except for peacekeepers who, during lulls in fighting, ventured outside their heavily fortified compound.

“I used to have daily regular customers, now they’re away,” said Carolina Rizqala, who runs a restaurant opposite the UN base. Lebanon has been at war with Israel for much of Rizqala’s life. She was born in 1985, during Israel’s 18-year occupation of Lebanon, and shudders at memories of Israel’s 2006 bombing of Beirut, where she grew up. “War isn’t good for anybody,” she said. “We have been suffering a lot since 2019. The damage has been done, but it could be much worse if this continues.”

The latest fighting has already uprooted tens of thousands across southern Lebanon, further widening gaping income inequalities. Farmers who fled further north left their fields untended and have struggled to find affordable accommodation. “The people who have money are living normally. They are not even affected by what’s going on in the south,” Rizqala said.

As we spoke, a siren began to blare warnings of an impending attack. The handful of peacekeepers who had been out shopping scurried back inside. Soon after, the shelling began.