To start at the start. The Cambridge Dictionary defines invasion as “an occasion when an army or country uses force to enter and take control of another country”. If the British didn’t, strictly speaking, use force to “enter” Australia in 1788, force was used in taking control of it. The British landed in my home state, Tasmania, in 1803. Within roughly 30 years, there were thought to be no Aboriginal people left on the island, the remaining population surviving on smaller islands in the Bass Strait, between Tasmania and the mainland.

The meeting of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australia was a head-on cultural collision that continues to reverberate to this day. Other countries with Indigenous populations are confronted with the same question: how do you balance western commercial culture, which sees land as an asset and resource, with an Indigenous culture, for whom land is mother?

The damage, particularly in remote Aboriginal communities, is chronic and ongoing. Amnesty International says that incarceration rates for Indigenous children are 26 times higher than for their non-Indigenous counterparts. Life expectancies for Indigenous men and women are almost 10 years lower, approaching 15 in the most remote areas. Child mortality is twice as high. The problems feed into one another and it’s easy to despair. To quote Australian songwriter Neil Murray: “Jesus can you mend this broken song?”

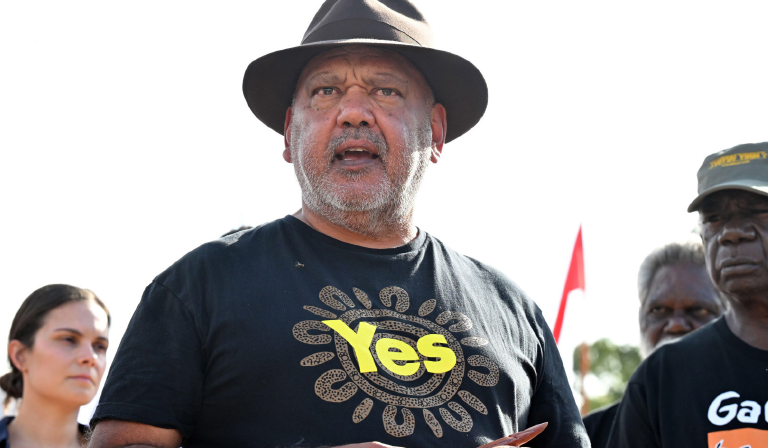

Before the end of the year, Australia will have a referendum on whether Indigenous Australia should have a “voice” enshrined in the country’s constitution. This follows a promise made on election night in 2022 by Labor’s incoming prime minister, Anthony Albanese.

The Voice will be a body that advises the Australian parliament and government on matters relating to Indigenous affairs. The government may also establish what is called a Makarrata Commission (from the language of the Yolngu people, and often translated as “treaty”) to “supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history”.

The principal fact about the Voice is that it will be subject to parliament. Gabrielle Appleby and Eddie Synot, both with the Indigenous Law Centre at the University of New South Wales, have explained that the federal parliament will, in the event of a Yes vote, decide “how many representatives will comprise the Voice, how they will be selected, what its internal processes will be, what powers it will need to perform its functions… and how the Voice will interact with the parliament and the executive”.

Stating what the referendum is about is the simple part. Stating what the referendum means in a polarised country is another matter. The Voice referendum has Brexit-like intensity in that it amounts to a defining moment in Australian political and cultural history. The last time Australians were confronted this directly about their relationship with their country’s Indigenous peoples was in 2014. Back then, Adam Goodes, an Aboriginal Australian rules footballer who had recently been named Australian of the Year, spoke out against public indifference to conditions in remote Aboriginal communities, saying “as an Australian, I find it embarrassing”. That went off like a volcano.

Outside views of Australia tend to be wrapped in dated national stereotypes that fail to capture the character of the place. The Melbourne suburb of Dandenong, for example, is home to 156 different nationalities. Similarly, Aboriginal Australia is a far more complex entity than it was in 1788. I have two grandchildren identified as Aboriginal on their birth certificates. Their middle-class Melbourne lives are very different from those lived by children in remote Aboriginal communities in the north of the country.

What has also become obvious to many non-Aboriginal Australians in the course of the referendum debate is that, in political terms, Aboriginal (black) Australia has a left, a right and a centre. The black left is voting No. To quote one of their number, senator Lidia Thorpe, the Voice “has no power”. The black left wants the treaty to come first—an agreement that proceeds from a recognition that Aboriginal Australia was, and is, a sovereign entity. The black right, a much smaller group, is against the Voice for reasons that chime with those of the white right, arguing that the referendum will divide Australians on the issue of race. But polls consistently say that 80 per cent of Aboriginal Australians want the Voice. That’s why I’m voting for it. I know it’s not perfect, but nothing in the history of black-white relations in Australia has ever been perfect, or ever will be.

The Voice has Brexit-like intensity—it amounts to a defining moment in Australian history

I have spent 40 years reporting on Indigenous affairs. During the 1990s, I was among those accused of promoting the so-called “black armband” view of Australian history, a term designed to discredit people seeking a closer relationship with Aboriginal Australia by implying we are motivated by guilt. But I wasn’t motivated by guilt, because—and I cannot stress this enough—not one of the great Aboriginal elders I met expected me to feel guilty. I am currently writing a book with Tasmanian Aboriginal elder Patsy Cameron, who has said: “Once the past is acknowledged, the guilt stays in the past.” None of the politicians and media personalities accusing me of being motivated by guilt actually engaged meaningfully with Indigenous people. A giant projection was happening.

Those identifying as Aboriginal or as Torres Strait Islanders (an Indigenous but not Aboriginal people) make up 3.2 per cent of the population. There are Australians who have never spoken to an Aboriginal person. And when two sides of a racial divide don’t speak, they only know one another through the media.

Here is a recent example from the Australian media—or, to be more precise, the Murdoch media, which at last count represented two-thirds of the country’s print newspaper circulation, controls Sky News Australia and is urging a No vote.

Stan Grant is a journalist and public intellectual of Aboriginal heritage who is at the cutting edge of the ever-more complex subject of Australian identity. His book Talking To My Country was a landmark work, confronting stereotypes that divide Australia into “black” and “white”. He wrote: “I have the blood of black and white in my veins. My fight with history is a battle within myself.… White and black: two worlds that even within me, bend to each other but still can’t quite touch.”

For its coverage of King Charles’s coronation, someone at the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) had the bright idea of adding Grant to a panel discussing the occasion. Asking Stan Grant to comment on the coronation of a British monarch is like asking Richard Dawkins to comment on the confirmation of an archbishop of Canterbury. Grant gave a frank assessment of the role that he believed the monarchy had played in the fate of Aboriginal Australia.

The ABC apparently received fewer complaints over Grant’s remarks than when it interrupted an episode of beloved crime drama Vera to tell Australia that Prince Philip had died. But in the days that followed, Grant was pummelled by Murdoch media outlets. Trolls swarmed on social media, and within three weeks a so-called “Christian conservative” had been charged in a Sydney police station with allegedly issuing threats against Grant and his family online. An obviously shaken Grant had already announced he was taking leave from his public duties.

Insofar as the referendum is being fought out in the media and on social media, the No case seems to be winning.

Uluru (colonial name: Ayers Rock) is the great weathered monolith at the centre of Australia. In 2017, after decades of activism and six months of regional dialogues right around the country, 250 Indigenous representatives gathered in Mutitjulu, at the base of Uluru, to arrive at a statement—known as the Uluru Statement from the Heart—to put to the Australian people. There was a walkout by seven delegates; those remaining agreed to a document that is both eloquent and powerful.

It reads, in part: “The ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown… we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.”

It is not flippant to reflect on the meaning of Australian nationhood through the lens of Australian rules football, the most popular sport in the country. It is a game with varied historical influences, but many Aboriginal people consider it theirs. Australian sporting culture, which is a large part of Australian popular culture, boasts many iconic Aboriginal figures. The Australian Football League has come out for the Voice, as have lots of other sporting bodies.

Last year, the Australian women’s netball team, the Diamonds, forfeited sponsorship from Australia’s richest person, Gina Rinehart. The Diamonds have an Aboriginal team member, Donnell Wallam. In a 1984 TV interview, Rinehart’s father, the Western Australian mining tycoon Lang Hancock, had said that Aboriginal people should be sterilised to “breed themselves out”. When the commercial partnership with Rinehart was proposed, the team reportedly rallied around Wallam and declined to wear the sponsor’s logo. Commentators and politicians on the right laid into the netballers, accusing them of being “woke”. The Diamonds stuck to their principles.

In the country at large, early polls showed that a clear majority of Australians supported the Voice. The race has since narrowed dramatically. Young Australians, who propelled marriage equality into law in 2017, are overwhelmingly for it. Older Australians are against, while those in between are not sure. Sceptics campaign under the anti-Voice slogan “Don’t know? Vote No”, insisting that the public don’t know enough about how the body would function to make an informed decision.

To succeed, the referendum proposal must win a majority of voters nationally, and there must also be a majority in a majority of states. Historically, only eight of the 44 referendums held in Australia since federation have resulted in a Yes vote: less than one in five. The chances of Yes winning one under a Labor government are not much higher than one in 50.

Senator Patrick Dodson, commonly known as the father of the Australian reconciliation movement, is an initiated Yawuru man and a former Catholic priest. Aged 14, after the death of both parents, he was sent from Katherine in the Northern Territory to western Victoria, a journey of several thousand kilometres through different climate zones, to attend a Catholic boarding school. He was, at first, the only Aboriginal pupil and, under the laws of the day, was not counted in the census. He became school captain, captain of the football team and acted to eliminate school bullying.

After leaving, he became a priest working in remote Aboriginal communities. Dodson told the local people that their ceremonies—traditionally split into “men’s business” and “women’s business”, used in initiation and imbued with sacred meaning—were the equivalent of what Catholics called “sacraments”. This freaked out the bishop of Darwin and, in the resulting furore, Dodson left the priesthood and began working with Aboriginal organisations. He rose steadily in national eminence, speaking to a vision of a racially reconciled Australia in much the same way that Obama spoke to the vision of a racially reconciled United States. On 28th May 2000, when 250,000 people of all backgrounds marched across Sydney Harbour Bridge in the Walk for Reconciliation, the turnout was justly seen as a measure of Dodson’s influence.

Dodson met his political nemesis in Liberal prime minister John Howard. In 1997, Howard declared that reconciliation would not work if it was “premised solely on a sense of national guilt and shame”. Again, the theme of guilt. That same year, a report by the Australian Human Rights Commission recommended that the government apologise to the “Stolen Generation”, the children of mixed racial background taken from their parents—ostensibly on welfare grounds—under a policy that had its origins in racial ideology. Howard refused to issue an apology, stating that he did “not subscribe to the black armband view of history”, and later peddled his own version of reconciliation which Dodson said amounted to the old policy of assimilating Aboriginal Australia into the dominant white culture. Howard, who is called the father of modern Australian conservatism, is campaigning for the No case. Unfortunately for the Yes case, Dodson had to take a leave of absence from his position in April due to serious illness.

The apology to the Stolen Generation was delivered 11 years later by Labor prime minister Kevin Rudd. It was well received, both in parliament and across the nation. But one Liberal frontbencher, former Queensland policeman Peter Dutton, chose to boycott the occasion. Earlier this year, Dutton apologised for having done so—but only after he was elected leader of the opposition in the wake of the 2022 federal election, which saw the Liberal-National Coalition routed and exposed as dangerously out of step with many of its former supporters. Dutton has since announced that he will be opposing the Voice, even calling for Albanese to cancel the referendum.

One of the architects of the Voice campaign, Cape York Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson, has a precocious intellect and a sharp tongue. In the wake of the 1992 Mabo case, which recognised traditional land rights, Pearson was deeply disappointed in what he saw as Australia’s failure to seize the moment for change. He came to the view that meaningful reform has to come from the conservative side of politics, because Australia is a conservative country.

It was in 1967 that Australia passed a referendum to finally count Aboriginal people in the census (and cede to the Commonwealth parliament the right to legislate on Aboriginal matters). But on that occasion, the Yes campaign had bipartisan support. During the long build-up to the announcement of the Voice referendum, Pearson spent years in dialogue with conservative politicians.

The day after Dutton announced he would be campaigning for No, Pearson said: “I couldn’t sleep last night. I was troubled by dreams and the spectre of the Dutton Liberal party’s Judas betrayal of our country.” He pointed out that the Liberals had had the preceding 11 years in government to work on a proposal for constitutional recognition and it had come to nothing. “I see the leader of the Liberal party, Mr Dutton, as an undertaker preparing the grave to bury [the Uluru Statement],” he said. Other scathing critics of Dutton include his predecessor as Liberal leader John Hewson, who believes that Dutton has deliberately sown confusion among Australians in his opposition to the Voice.

Young Australians, who propelled marriage equality into law, overwhelmingly support the Voice

Another former Liberal prime minister, Tony Abbott, had declared in 2014 that he was prepared to “sweat blood” for the recognition of Indigenous Australians in the constitution; now he, too, announced he was opposed to the Voice because it “entrenches race in the constitution”, arguing elsewhere that “I don’t think anyone should have a special voice. I think everyone should have the same voice, and the voice of all of us is the national parliament”. (This drew a volley of responses on social media about the lobby groups which now riddle Canberra and enjoy privileged access to government.)

Repeated claims that the Voice makes for constitutional problems were addressed publicly by Australia’s solicitor general, Stephen Donaghue, in a legal opinion presented to parliament. Donaghue wrote that the proposed model for the Voice “will not fetter or impede the exercise of existing powers” of parliament or the executive government. He added that under the proposed new section 129 of the Australian constitution, the Voice will have no power of veto. While it would be entitled to make representations, there would be no obligation to accept its advice. It follows that while the Voice may lead to discussions on a treaty, it would not be within its power to unilaterally negotiate or enact one.

Donaghue’s opinion was bolstered in late July, when eight former senior judges wrote that the Voice would not “disrupt government or destabilise the presently stable and appropriate division of power between the parliament, the executive and the judiciary”.

The Murdoch media has announced that, through Sky News Australia, it will be running a dedicated programme on the Voice 24/7 in the run-up to the referendum.

Trump ally Roger Stone, outlining a rule of political combat that chimes with populist campaigning everywhere, advised: “Open multiple fronts on your enemy. He must be confused, and feel besieged on every side.” On 13th July, Guardian journalists Josh Butler and Nick Evershed revealed that a leading No campaign organisation called Advance was running three Facebook pages, each with seemingly contradictory messages. One page was for conservatives, one portrayed itself as a neutral news source and one was for progressives wishing to vote No.

Trying to describe the No campaign is like trying to describe the contents of a rubbish tip. In mid-July, the ABC reported that an anonymous pamphlet was circulating round Melbourne, promoting claims that “the Voice forces Australia into Treaty” and the result “could include reparations, a financial settlement, the resolution of land water and resource issues…” Australians, this pamphlet continued, would be “forced to pay rates/land tax/royalties to the Voice”. This is an incoherent campaign of fear.

Trying to describe the No campaign is like trying to describe the contents of a rubbish tip

On the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) the casual observer finds a meme of three photos: the first of young Germans alongside the words, “No one blames them for the Nazis 81 years ago”; the second of young Americans alongside the words, “No one blames them for Hiroshima 75 years ago”; and the third of young Australians alongside the words, “So why do white Australians still get blamed for what happened over 200 years ago?” The theme, once again, is guilt.

Given the right—or wrong—circumstances, the most fraught prejudices can resurface. In 1835, when a group of colonial adventurers embarked on a land grab that would have won them a large chunk of southeastern Australia, they fortified themselves with stories that the Aboriginal people practised infanticide, this being taken as evidence that they were ripe for “civilising”. Sure enough, the infanticide trope has resurfaced on social media and, with that, we are back to the start, to the brutal birth of my nation.

Within a few weeks, what had begun as an inspiring idea had disappeared in a fog of negativity. In the polls, the Voice slumped like a sick man and is now expected to lose. The Yes campaign has been lacklustre. It needs to excite the nation, perhaps by holding an event at an iconic venue—somewhere like the Melbourne Cricket Ground—with popular bands and celebrities (and perhaps ending with the Diamonds, now world champions).

The campaign has lacked a leader. Anthony Albanese is what might be termed a post-personality politician, who won office in part as a reaction to leaders like Boris Johnson, Donald Trump and Australia’s very own charlatan, Scott Morrison. That said, the Albanese government still leads comfortably in the polls, while the Liberal party has moved closer to becoming the Australian MAGA party.

The tragedy of the Voice is that it’s an offer made in a spirit that many Australians have never experienced and would scoff at if you told them. Nonetheless, as a historical document, the Uluru Statement from the Heart will stand like the rock it was named after. Later generations will see it as a dignified and respectful call to non-Aboriginal Australia to address a dire situation born of historic injustice. The No case will be seen for what it is: manipulative mayhem.

The offer implicit in the Voice will not come again. Some Australians won’t care. One of the best insights I ever heard about Australia came from English actor Pete Postlethwaite, who became immersed in these issues after touring the country in 2003. He said that terra nullius (the land of nobody) is more than the legal doctrine under which Australia was settled (or invaded), it is the primal creation story of the modern state of Australia—and it continues in our psyches. Most non-Aboriginal Australians live as if Aboriginal Australians don’t exist. For that reason, a victory for the No campaign may not dent Albanese’s immediate political fortunes in any major way, though it will certainly dent his legacy.

But if the referendum is won by the No case, it won’t be the end—just the start of the next chapter. The shame that will attach to this episode will only grow with time. So-called progressives who have voted No will have to confront the fact that, having rejected Aboriginal Australia’s proposal to alleviate the chronic problems afflicting the community, they have neither the mechanism nor the power to implement any proposal of their own—if, indeed, they have a concrete proposal at all. Nothing can be done without the cooperation of Aboriginal Australia, which they will have specifically rejected.

And defeating the Voice does not mean defeating the idea of a treaty. There’s a generation of young, educated Indigenous peoples emerging who want action. Then there are the rest of this generation of Australians, confronted daily with evidence of their parents’ political delinquency on major issues such as climate change. My daughter Frankie teaches English in Dandenong, the outer Melbourne suburb with 156 different nationalities. Among the kids she teaches, a treaty is a “no-brainer”.

Australians are being given a choice in how we rectify a great historical imbalance—one that goes to the core of our national history. The Voice is the civil way out. It seems we’re not going to take it.