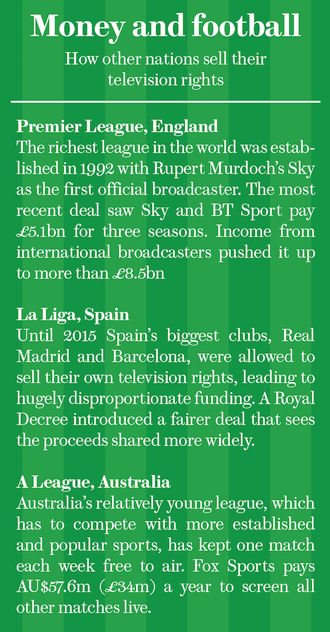

In late June this year, on the final day of the football season, Boca Juniors were confirmed as the champions of Argentina’s Primera, the country’s equivalent of the Premier League. The usual delirium in the club’s stadium and in its tight-knit neighbourhood in Buenos Aires was matched in the Casa Rosada a few miles north where President Mauricio Macri, once president of Boca Juniors and a very open and partisan supporter, was also celebrating. As well as his side’s success, Macri had other reasons to be satisfied. The end of the season also represented an important turning point in the political economy of Argentinian football, one that speaks to the wider economic transformations that the new right-wing president has been pursuing. Boca’s final match of the season, along with every other first division match, was available on television live, direct and free to everyone in Argentina through the semi-public operation Fútbol Para Todos (Football for Everyone). Not for much longer, though. Macri’s economic reforms, which seek to overturn the socialist approach of his two predecessors, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her late husband Nestor, even extend to football. When the new season kicks off in August, Argentina’s biggest games will be available only to those with a cable subscription to the new rights holders Fox and Turner. An electrifying progressive experiment in football broadcasting is over. The creation of Fútbol Para Todos in 2009 was perhaps one of the most emblematic policies of Cristina Kirchner’s left-wing government, both in terms of content and style. State intervention, which her government used to advance the material interests of the poor, from creating a universal social security system to massively extending workers’ rights, was in this case used to give “the people” something they very much wanted but often couldn’t afford purely because commercial interests had conspired to shut them out. It was also a political weapon, used with all of Kirchner’s characteristic aggression and guile. Crisis was, as so often, the mother of opportunity for this radical, populist move. It emerged out of the confluence of two events: the government’s long-term struggle with the Clarin media group and a not uncommon crunch in the finances of Argentinian football clubs. In August 2009, with the new season due to begin in just a few weeks, nearly a dozen clubs had been suspended under new Argentinian Football Association (AFA) financial regulations, because they could not demonstrate the capacity to pay their bills. Matters were made worse when the football players’ union won a case in court in pursuit of unpaid wages and many clubs had their assets frozen. The Clarin group, the largest Argentinian media conglomerate, owns hundreds of newspapers, radio stations, television channels and digital outlets, and had been in total control of Argentinian football since 1992. It is, needless to say, on the right of the political spectrum. The long-standing antipathy between the group and the Kirchners had reached a new pitch in 2008 over the issue of Argentina’s soya bean export industry. It had been enjoying exceptional profits on the back of China’s long boom and the government imposed a very stiff tax. Clarin was among the most forceful in their opposition to this levy. The government hit back, refusing to speak to the group’s outlets, blocking its acquisition of a controlling stake in Telecom Argentina and in 2009 passing an audio-visual media law. This gave the newly established audio visual commission the authority to break up the largest media groups, forcing them to relinquish many of their media channels and licences (a process that continues to drag unresolved through the Argentina courts). It was in this context that the government began to consider getting into the football business. “We were paying millions of pesos to the Teatro Colon (the national theatre) for an audience of just 2,000,” said Gabriel Mariotto, the head of the audio visual commission. “Thinking about football put on the table all of the issues around access and equity.” There was a strong case, he argued, for the state to invest in the football industry in some way, and that free access to televised football was, if not a right, a basic precondition of the good life in Argentina. Whatever the balance of motivations inside the government, and whatever one thinks of the Clarin group’s politics, its whole approach to football was remarkably mean-spirited. The game was covered by its subsidiary Torneos y Competencias—slogan “We are the owners of football”—who for over 15 years had ensured a complete blackout on any images from the league’s games until late on Sunday night, when the free-to-air highlights show

Fútbol de Primera finally arrived—less

Match of the Day, more Match of Yesterday. In the meantime, other channels and the viewing public were so desperate for snippets that they were tuning into hand-drawn and computer graphic recreations of goals, real-life re-enactments of contested incidents and cameras turned towards the fans for the entirety of a game.

![article body image]()

Given the country’s fanatic mania for football, it was widely thought that Clarin were significantly underpaying the AFA for their monopoly. Horacio Gennari—a television executive who went on to serve on the board of Fútbol Para Todos—had been making the case to the AFA and its autocratic president, Julio Grondona, for years but to no avail. Then in the summer of 2009 the call came to go and see them. Grondona preferred to hold meetings away from the grandeur of the AFA’s offices, instead opting for a small room in the back of a petrol station in Sarandi, an industrial neighbourhood in outer Buenos Aires. It was kept empty but for a desk, four chairs and a single light bulb. Even Sepp Blatter, President of Fifa, was received here. It was not for nothing that Grondona acquired his nickname, “Don Julio.” He had begun with a small hardware store and the presidency of the tiny club he founded in the 1950s called Arsenal FC. (Argentina’s military arsenal was housed nearby). He became president of AFA in 1979, an office he never relinquished, and steadily added further sinecures at the South American football federation, Conmebol, and Fifa. While remarkably unostentatious in public life, he had also acquired a very substantial property portfolio in Buenos Aires, the petrol station included. On arrival Gennari handed a slim briefing to Grondona. It laid out the research and international comparisons showing that Clarin were indeed underpaying and that a very much larger television rights deal could be achieved. Grondona placed the file on the table and spoke. “Horacio, so many words. I’m in my eighties Horacio. Show me the important part.” Gennari later recalled. “I opened the file and pointed to the executive summary. ‘Horacio, you know me. I don’t need all this, just the number.’ So I turned to the final page of the conclusion and pointed to the figure I thought the AFA should be getting for its television rights—600m pesos (approximately £27.5m). Grondona tore the page out of the brief, folded it, neatly placed it in his jacket pocket and left.” Grondona went to see Clarin and gave them one last chance to up the money, which they declined. Then he headed for the Casa Rosada to meet Kirchner where she asked what the bill would be. Grondona wrote down the figure and the deal was informally agreed and signed on a napkin. Fútbol Para Todos broadcast its first game on 21st August 2009. The government insisted that there would be no commercial advertising or sponsorship for the programme. Instead a huge slice of the government’s fast-swelling advertising budget was redirected towards football. Presenters and commentators were recruited from outside the Clarin empire, many from radio and the provinces, including a fair number whose pro-government

Perónista sympathies were well known and often broadcast. Javier Vincente, known as “El Militante,” was particularly vocal in denouncing Macri before the presidential elections and warned of the consequences for the future of Fútbol Para Todos, if he won. Is such politicisation problematic? Certainly. And it was distasteful to parts of the audience, not only to the Clarin group who compared the operation to Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela. But the viewing public loved it. Ratings were immense for the biggest games, and in the country’s interior in particular where there has been much more poverty and much less cable television, the service proved hugely popular. It is, especially from a British perspective, worth pausing for a moment here. Imagine that Gordon Brown’s government had persuaded the Premier League to break its contract with Sky, paid them almost triple the amount for the rights, and then made the Premier League (not to mention the rest of English professional football) available for free on UK television. Imagine too, despite a lot of huffing and puffing from the News International stable, that the policy had huge public appeal and legitimacy, not merely because it delivered a lot of free football, but because the claims made about football’s cultural status and meaning rang true for much of the population. Even Macri, who was proposing the privatisation of many state enterprises and the slashing of energy and transport subsidies went into the 2015 presidential election claiming that Fútbol Para Todos would continue.

![article body image]()

The reason that this audacious scheme could acquire such political weight is best grasped by a trip to an everyday Argentinian football game. I went to see Racing Club at home against San Lorenzo on a cold Saturday night in Avellenade, a huge industrial sub-city on the south side of Buenos Aires. These clubs are two of the traditional “big five” but neither would last a moment in the Premier League, and would struggle at the lower end of the Championship. The football, played on a very poor quality pitch, was not without its moments of class, but it was slow, dull and peppered with mistakes. The crowd, on this occasion, was entirely peaceable, but Argentina’s awful record of football violence and disorder is well earned. The Argentinian football public knows this. They watch the Champions League and European football avidly. They understand the consequences of their position in the global football political economy, in which Argentina exports more players than any country other than Brazil. In some years the country makes more from transfer fees than the exports of live animals—not an inconsiderable sector in Argentina. Consequently even the best clubs are staffed by the very young, the very old and the going nowhere. Lionel Messi, the nation’s greatest contemporary player, has not started a single professional game in the country, spending his entire career at Barcelona. Yet attendances are high and even increasing. Racing attracted perhaps 28,000 that night in weather that would pass as balmy in Newcastle but was considered worryingly wintry in Buenos Aires. The atmosphere and noise levels exceeded the average Premier League game by some way, and were given shape and volume by the organised fan groups that occupied the terraces behind the goal. The animating spirit is known locally as

aguante—resilience, endurance, the capacity to survive in the face of unfair odds. Argentina’s popular classes may be on the wrong end of the global economy, football or otherwise, but they are—in the ritual world of the football stadium—not about to capitulate. Moreover, the clubs have remained members’ clubs, rooted in their communities, electing their officials and offering a range of social facilities. The significant rise in the number of women interested in football, some even braving the hitherto macho monoculture of the stadium, has cemented this. There is, unlike almost everywhere else outside of Europe, not a trace of support for foreign clubs. Any notion that the game had ceased to be the primary public expression of Argentinian national identity (and its neuroses) was quashed by the nationwide standstill occasioned by the latter stages of the 2014 World Cup in which Argentina would lose to Germany by a single goal. This is the context in which the notion that access to football on television has become a matter of social policy, even perhaps a matter of rights. The Kirchner government may have won that argument but reality has proved obstinate. As with her administration’s broader economic policies, Fútbol Para Todos staved off a disaster, and aided the have-nots, but it failed to tackle many of the deeper problems of Argentinian football. For a start, the clubs proved no more adept at managing their income, controlling their costs or paying their taxes, let alone effectively commercialising their operations. More pressingly the enduring problems of Argentinian football’s corrupt governance were ruthlessly exposed when Grondona finally died at the age of 82 in late 2014.

![article body image]()

Truly nothing became him like his passing, for “Don Julio” went out on top: president of the AFA for almost four decades, vice-president of Fifa and Conmebol. For a man who began with one hardware store he bequeathed a very considerable estate and was seen out with a funeral just short of a state occasion. All this merely months before the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Swiss investigations into Fifa finances, vote buying in the allocation of many World Cups, and the sales of television rights for South America’s international competitions would unambiguously expose him as the corrupt, shameless rentier he had always been. But venal as he was, he had brought a degree of order and purpose to the otherwise deeply and bitterly divided political worlds of Argentinian football. Since Grondona’s death, the AFA has lurched from crisis to crisis. For more than a year his position went unfilled and the organisation remains dysfunctional. It was just this kind of bureaucratic incompetence that Macri, who himself used football to climb to the top, promised to tackle in his election campaign for the presidency in 2015. Macri is the scion of a rich industrial family and worked in the family business under his father’s beady eye. In 1995 he was elected president of Boca Juniors—the epitome of

porte˜no working-class soccer—and, at the turn of the century, he presided over the club’s most successful ever period on the field as national, continental and global trophies piled up. He was defeated in his first foray into politics, losing a run-off for the Buenos Aires mayoralty in 2003, but he then won a term as a Congressman in 2005. In 2007 he triumphed in a second mayoral election and ran the city for eight years until he was narrowly elected president in 2015. Along the way Boca Juniors gave him visibility, a certain kind of authenticity, legions of Boca fans chanting club songs at his rallies, and a story of entrepreneurial zeal. Under Macri’s command Boca Juniors acquired the nation’s first executive boxes, had the first proper marketing department in the game, and turned itself into a global brand whose shirts and logos, while not as widespread as Barcelona or Manchester United, have a real global presence. It was this business savvy that his supporters claimed would turn around the sclerotic socialism of the Kirchner years, with a policy programme of privatisations, pubic expenditure cuts, and deregulation.

In the realm of football Macri began his term of office by appointing showbusiness and television impresario Fernando Marin to run Fútbol Para Todos. Marin had also been president of Racing Club between 2001 and 2008, running it effectively as a private enterprise rather than as a members’ club, and securing a long-awaited championship before he ran it into bankruptcy. In his new role he began by changing the tone of the show, insisting on presenters wearing ties and jackets, stipulating no cursing, and an end to any political commentary. By this point the government was paying 1.5bn pesos for the 2015 season and 1.85bn pesos in 2016. At £75m and £92.5m respectively that is very small beer compared to the cost of European football rights, but in an era of sharp austerity, Fútbol Para Todos was in the firing line, ideologically unsustainable for the new government. Government advertising was reduced and then withdrawn altogether. Private advertising was permitted, as were rebroadcasts by private channels. The games of the second division were sold off to a reborn Torneos y Competencias and then, in spring 2017, the AFA announced that it had sold the rights of the newly constituted Argentinian Superleague to Fox and Turner. The Fútbol Para Todos experiment was over. Argentinians who want to watch next season’s games, beginning in August, will have to get a cable connection and subscription. As with his wider economic agenda, Macri has followed the textbook. Argentina has made deep cuts, carried out the simpler privatisations and normalised its relations with international capital markets. There is, however, as yet little sign of an upturn in the economy or the promised new wave of investment. Unemployment and inflation are stubbornly high and the country’s still powerful trade union movement continues to resist the government’s plans. Macri is likely to meet similar opposition, as he takes his football reforms forward. Emboldened by the end of Fútbol Para Todos, Macri is proposing that Argentina’s football clubs should be converted from social organisations to private companies, a course he tried to pursue when president of Boca Juniors. The fans at Boca have not forgotten his earlier presidency. I met Luciano Caldarelli, a member of a group of fans called Boca Pueblo and part of a new wave of fan organisations called El Hincha Militante. They stand entirely to one side of the Barra Bravas (the name given to organised fan groups), seeking to mobilise fans around the running of the club. Recalling Macri’s stint in charge he reels off a list of criticisms: “He cut the money to the social side of the club, he cut the money to other sports. He raised the membership fee, tried unsuccessfully to change the constitution of the club to drastically reduce voting rights of members, raised ticket prices and stopped giving free tickets to the club’s neighbours.” He also tore down the stadium’s famous tower to build more VIP boxes, and negotiated eye-wateringly expensive building contracts. Boca is currently run by Daniel Angelici, a close ally of Macri, who offers a foretaste of how private clubs might conduct themselves. This new generation of fan activists railed against what Caldarelli despairingly calls “the shopping stadium.” In alliance with a Saudi Arabian property developer, Angelici had proprosed building a new stadium, that was in effect a glorified shopping mall, on one of the free public parks and open green spaces in Boca. There were large, vociferous and widespread protests that forced the club to abandon the plan altogether and destroy what remnants of trust existed between the management and much of the fan base. They, and like-minded fans now joined in a national alliance of hincha militantes, will oppose any move to privatise clubs with equal vigour. And then there is the departure of Fútbol Para Todos. Gabriel Mariotto believes that most of the country have yet to realise quite what has happened. And when they do? “When people realise that they have put football into private hands and they cannot watch the big game, Boca and River, there will be sadness and anguish and that’ll turn to anger. There will be demonstrations in the stadiums and in the streets and there will be electoral repercussions.” So far, the Argentinian electorate has been relatively patient with Macri, but governments every-where are beginning to pay the electoral costs of austerity. It would be remarkable, though not inconceivable, if the privatisation of football on television could prove to be the most incendiary squeeze of the lot.