“Housing is not a question of Conservatism or Socialism”, said the Tory housing minister and future prime minister Harold Macmillan during the 1951 general election campaign, “it is a question of humanity.” His party won the contest with the help of a promise to build more council homes than Labour, a “great housing crusade” that saw 245,160 completed in 1953, the record for a single year. It is a mark of the success of the outgoing Attlee administration that Macmillan stole its policies, just as New Labour later felt obliged to adopt aspects of Thatcherism in order to get elected.

The Labour government that had come to power in 1945 was as radical and determined in its approach to housing as it was in health. Despite austerity, it started building council homes in unprecedented numbers. It launched the programme of creating new towns in which 2.8m people now live, and would eventually deliver the successful new city of Milton Keynes. The Attlee administration was prepared to use wartime powers of requisition to take over empty properties to house people in need. It set ambitious policies followed by all governments until Margaret Thatcher’s, which at their peak in 1968 delivered more homes of all types, public and private, than in any other year before or since.

Britain, especially England, is now in a seemingly endless housing crisis. Average house prices stand at about nine times average annual earnings (compared with a ratio of about three to one on the 1980s), making home ownership an impossible dream for millions. This in turn puts pressure on rents, which are at their highest ever levels. Numbers of socially rented homes are falling. Many Britons expect to spend their lives in insecure, expensive and sometimes substandard rental accommodation.

All of this has effects on relationships, families, well-being and quality of life. If 60 per cent of your income goes on rent, that fact will dominate whatever other financial gains and losses come your way. There’s a new class division—generational and regional, as well as social—between property haves and have-nots.

The question is: can the ideas and methods of the 1940s help us now? The preferred option of recent governments—to “reform planning” and “slash red tape” in the hope that an unshackled private sector will build new homes of the types and numbers required—has failed. Is there then a role for a more interventionist approach, which includes such dread measures as compulsory purchase, state-led planning and large-scale public expenditure?

Labour in 1945 was heir to a history of public housebuilding that went back to the very first council homes, the 146 units built in the two four-storey blocks of St Martins Cottages in Liverpool, completed in 1869. This once-novel idea was encouraged by legislation towards the end of the 19th century that empowered local authorities to provide housing. After the First World War, it was boosted again by the demand for “homes for heroes”, which led to the creation, for example, of the 26,000-home Becontree Estate on the eastern edge of London.

The post-war government was also influenced by the writings of Ebenezer Howard, first published in 1898, which called for the creation of garden cities: “wholesome and beautiful” communities of 32,000 people where buildings and nature, and industry, agriculture, homes and leisure, would be harmoniously integrated. Howard was in turn shaped by the American political economist Henry George, whose popular book Progress and Poverty, first published in 1879, argued that wealth in property was social rather than private. It was, he said, a creation of the collective building of such things as businesses and infrastructure, and that this wealth should therefore be turned through taxation to public benefit. Howard’s garden cities depended on a version of George’s theory: they would be funded through capturing the “unearned increment”, the uplift in value that came with development, and turning it not to private profit but to public assets such as parks and educational institutions.

Labour’s policies from 1945 emerged out of a ferment of debate about the ways in which a better society might be built after the Second World War, driven both by the approximately two million homes destroyed or damaged through bombing and the decades-long desire to replace urban slums with more salubrious and less crowded places to live. Such was the interest that British prisoners of war created a “town planning group” in Stalag Luft III, the camp made famous by The Great Escape. The Labour administration passed several acts of parliament with the aim of achieving well-planned development and state-built housing. The politician in charge was Nye Bevan, whose remit as minister of health included housing, reflecting a belief that your physical wellbeing is inextricably connected to the place where you live. The creation of the National Health Service and the building of decent homes were two aspects of the same project.

The aim, said Bevan, was to “solve, first, the housing difficulties of lower income groups.” The “problem of the higher income groups in the matter of housing” had, he believed, “been roughly solved” before the war by the private sector. Quality was for him as important as quantity: “we shall be judged in a year or two by the number of houses we build”, he said, “but in ten years’ time we will be judged on the type of houses we build.” He believed that new developments should achieve the “living tapestry of a mixed community”, social segregation being “a wholly evil thing.” If, he said, “we are to enable citizens to lead a full life, if they are each to be aware of the problems of their neighbours, then they should all be drawn from different sections of the community.”

The means to his government’s ends were extensive and sometimes drastic: requisitioning and compulsory purchase; public subsidies and low-interest loans; and a requirement to local authorities that only around 25 per cent of new homes could be built by the private sector. There was a “development charge” whereby developers had to pay the whole of the increase in land value following planning permission and development. The latter proved unworkable and short-lived, but in general the policies were effective. Between 1945 and 1951, 800,000 council homes were built and—as Macmillan’s words and actions demonstrated—the change in political attitudes lasted a generation.

There were the new towns, launched by an Act in 1946, created by publicly appointed development corporations armed with powers to buy, plan and develop land, who could invest upfront in the roads and schools and other essentials of a new community. These were funded with the help of the uplift in value that came through investment in infrastructure and the change of use of land from agricultural—which, by turning this uplift to public benefit was effectively a version of Howard’s “unearned increment”. Low-interest government loans assisted the process. Thanks to this method, the entire new towns programme ultimately cost the Treasury little or nothing.

Then, alongside this promotion of construction and development, came equally consequential legislation aimed at limiting it. The Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 introduced the requirement to gain planning permission. While individuals might own land and buildings, the rights to develop them were effectively nationalised, and would be selectively returned to landowners when they got permission. The idea of green belts, which originated in the early 20th century as a means of giving the urban poor access to nature, was expanded and fortified. Underlying the endeavour were the aims of alleviating urban squalor and overcrowding, providing new homes and protecting the countryside from sprawl, all under the benign direction of government.

That was then. Now we face another housing shortage, albeit for different reasons than aerial bombardment and an inheritance of Victorian slums. The current problem is one of affordability and access to housing. Meanwhile, half of the 1940s legacy—the one about planning and building driven by the public sector–has largely been dismantled. The other half, about restriction and control through the planning system, including the protection of green belts, remains powerful. What was meant to be a complementary relationship between development and control has become adversarial. An opposition has grown up between the interests of those who would benefit from new homes and those who want as little change as possible to their views of the countryside.

A major cause of this crisis is the way that governments, going back to Thatcher, have encouraged house price inflation, celebrating it as a sign of economic virility, and exploiting it as a source of (somewhat illusory) growth. Fiscal policy, such as the absence of tax on the capital gains you might make on your own home, encourages owners to invest as much as they can in it. Quantitative easing, and low interest rates set by the Bank of England, have further pushed investment towards capital assets, including housing.

In times of crisis, instead of allowing values to adjust—as believers in the free market should do—governments have rushed to prop them up. In the aftermath of the 2008 crash the coalition government introduced Help To Buy, in which it loaned first-time buyers money to cover their deposit. During Covid, Rishi Sunak temporarily suspended stamp duty on the first £500,000 of a property. Both measures were introduced in the name of helping first-time buyers—as in some cases they did—but the main effect was to increase prices and thus the main beneficiaries were housebuilding companies and people who already owned.

There is also a straightforward issue of supply and demand. The population of the UK, in the very possible event that it returns to pre-covid and pre-Brexit levels of increase, could rise at a rate of more than 600,000 people a year, which would on average require about 250,000 additional homes annually.

In theory this ought not to be too hard, given that only 6 per cent of Britain is built on—a figure that includes parks, gardens and other green spaces within towns and cities—and that buildings themselves occupy 1.4 per cent of the land area. It would take only a sliver of the remaining 94 per cent to meet the need. In practice, of course, it is extremely difficult, due to the ferocious opposition that new development arouses, especially in rural and green belt areas, and the reluctance of private housebuilders to construct homes at a rate that would reduce the price of their product.

Nor is it simply a matter of churning out residential units. Successful communities need schools; places of work, community and leisure; parks and infrastructure. They need a range of homes and tenures and different levels of affordability—Bevan’s “mixed communities”—and not just the lucrative private homes that the big house-building companies prefer to provide. As the planning barrister and author Hashi Mohamed has pointed out, austerity-driven cuts to local authorities have left planning departments under-resourced, which places a further drag on building.

Where such communities might go is a vexed question. The official preference, since Tony Blair’s government if not before, has rightly been to develop brownfield sites first, and at high density. As a result, cities like London and Manchester now have thick clusters of residential towers on ex-industrial land. But even Blair’s government set a target that 60 per cent of development should be of this sort, which left a sizeable 40 per cent to be built elsewhere. Most of the more viable brownfield sites have since been built on, leaving a remainder that are challenging and expensive to develop.

The obvious alternative is to build on land in the designated green belt around cities and on greenfield sites outside them. This is an idea that is and should be approached with extreme caution, as the limiting of sprawl and the protection of the countryside are huge successes of the British planning system. But it’s not tenable to insist forever on lines drawn 60 or more years ago to define the edges of cities. Given that the London green belt is three times the area of the city itself, it’s not outrageous to propose that a small proportion of it be given over to alleviating the capital’s expansion.

Most of this land, it’s true, is in some way spoken for. It’s part of someone’s view, or walk, or livelihood, and the resistance of nimbies to almost everything is the more understandable given the mediocrity of most new housing, and how little it gives to the communities it adjoins. But it doesn’t have to be like this.

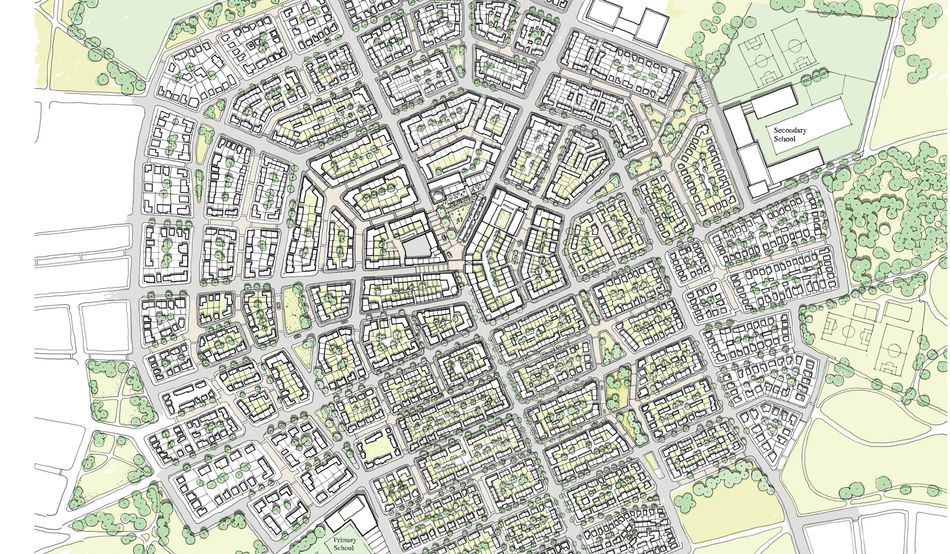

New developments can bring the population that helps keep schools and pubs and bus services alive, and can provide homes within reach of younger generations. Done right they can improve the local environment. Nine years ago, the urban design consultancy URBED won the Wolfson Economics Prize with its proposal of Uxcester Garden City, an imaginary extension to an existing city.As well as being a sustainable mixed-use development with public facilities and public transport, it would transform dull and ecologically impoverished fields into public parks.

It’s easier to achieve the numbers and quality and amenities required by building at scale, rather than in small incremental additions, which is one reason why the concept of new towns (which should include large extensions to existing towns and cities) keeps coming back. Starmer has talked of a “new generation of Labour new towns”. The idea is not fantasy. The developers Urban&Civic, with the Wellcome Trust, are successfully building the 5,982-home Houlton, outside Rugby, and have several similar projects on the way. The North-West Cambridge Development, (also known as Eddington), backed by the city’s university, will, when complete, provide 3,000 homes and 2,000 student bedspaces. Poundbury, the Dorset-backed extension to Dorchester initiated by King Charles, includes about 2,000 homes. All are genuine towns, not just agglomerations of units, with public buildings and spaces and networks of streets that encourage walking and cycling.

There are even realistic ways in which this building can be paid for. For example, one way could be an updated version of the capture of land value that built the post-war new towns, which went back to Howard’s “unearned increment”. In this scenario the government sets up development corporations that buy land, draw up plans, obtain permissions, install infrastructure and, in partnership with the private sector, build, sell and rent out homes. In the process the value of the land goes up many times, which in principle means that the whole undertaking can be self-financing or even profitable. It needs both a long-term view and significant upfront investment, neither of which are within the capabilities of most commercial house building companies.

New towns, though, are not going to address housing need all by themselves. If the target, as both Starmer and Sunak have said, is to build 300,000 homes a year, that would require an unfeasible annual output of over 50 Houltons or nearly three Milton Keynes. There is also the crucial and under-discussed question of the environmental impact of this construction. Will Hurst is managing editor of the Architects’ Journal, which started the Retrofirst campaign to encourage the reuse of existing buildings. “No one at the top of politics,” he says, “is aware that you can’t build 300,000 houses a year and hit the country’s carbon target.” According to one study, building at this rate, combined with emissions of existing stock, would use up 104 per cent of the UK carbon budget by 2050.

It is therefore essential to work out ways to address the housing crisis that don’t involve digging holes and pouring concrete. Given that the current situation is partly a creation of economic and fiscal policies, it would be nice, if over-optimistic, to think you could fix it with financial wizardry, without laying a single brick. Future chancellors could as a minimum avoid the measures that have pushed prices up and make it a stated goal to keep house price inflation to zero. Stamp duty, which acts as a brake on older people downsizing from their family homes, could be reformed. A tax—albeit an electorally challenging one—could conceivably be introduced on under-occupied homes.

Starmer talks of a ‘new generation of Labour new towns’

It is equally important to encourage the re-use of existing buildings as homes. The abolition of VAT on renovations and conversions (which, absurdly, encourages demolition) would be a good start. So would the promotion of intelligent adaptations of redundant office and retail space—that is to say, something other than the tiny and barely habitable residential units that developers have carved out of commercial buildings, as a result of the government’s decision to remove the need for planning permission for such changes of use.

There’s also an opportunity in the fact that the housing crisis is regional in nature. The problems of affordability and supply are particularly intense in London; cities including Oxford, Cambridge and Bristol; and some rural areas, especially in southern England. All over the country there are very similar housing types—Victorian terraces, interwar semi-detached—whose value might vary by a factor of 10 or 20 depending whether they are in Fulham or Gateshead. There are also more redundant industrial buildings that haven’t yet been converted, like their cousins in London, to apartments. Historic England estimates that 42,000 homes could be created out of empty northern textile mills.

One might hope—though thinking on this is sketchy—that hybrid and remote working might enable some employees to live further away from big expensive cities, especially London, and thereby disperse the pressure on prices. One might also hope that a future government would actually be able to achieve some of the promises of regional regeneration contained in this government’s “levelling up” agenda.

The world now is very different to how it was in Bevan’s day. The war engendered both faith in large-scale public endeavours (if you can pull off D-Day, then building Harlow and Stevenage shouldn’t be too hard) and a sense of being all in it together, from which modern nimbyism has travelled very far. The colossal increase in property prices since then means that there is much more at stake for those who think the value of their homes is threatened, and opponents of development are more organised, resourced and motivated. There is also a climate emergency.

It also has to be acknowledged that plenty went wrong with the mass house-building programme he initiated. As council estates became housing of last resort, serving those to be considered in greatest need, they created the social segregation that he abhorred. It is no longer politically or practically feasible, as it was for him, to sweep away swathes of inner cities and rebuild them with council housing. It is surely possible, though, to learn from past mistakes.

Now, as then, there is serious housing need, and an opportunity—social, economic and political—in putting it right. It will take courage and skill and the sort of determination that previous governments have managed to find for roads, railways and airports. Bevan had those qualities, and many of his ideals and methods are as good now as they were in his day. The alternative, of letting this situation drift on forever, will lead to continuing immiseration and stagnation.