We learned recently that more than one million UK children now live in households affected by the two-child limit—the policy that, since 2017, has restricted means-tested support to just the first two children in the family. Supposedly introduced to ensure fairness in the benefits system, it would have been hard to design a policy more effective at pushing up child poverty.

As our new research shows, poverty was already rising sharply among families with three or more children in the years before the two-child limit took effect. Our analysis highlights a little noted and little discussed fact—almost all the change in child poverty in the UK over the last 25 years has taken place among larger families (Figure 1). This is true in the good years when child poverty was falling, as well as in the more recent rise.

Figure 1: Child poverty in larger and smaller families, before housing costs (left panel) and after housing costs (right panel). Poverty measured against a line of 60% equivalised median income

Source: Authors’ calculations using HBAI 15th edition 1994/95-2019/20. UK Data Service. SN: 5828. Note: Shaded areas show 95% confidence intervals

These trends are striking, given that until the two-child limit there was really no policy directly targeting larger families—either for better or worse. What explains these patterns, and what do they tell us about different child poverty strategies and their effectiveness?

First, our analysis underlines the vital importance of social security support for families with additional needs. This is no new or original insight: it was identified in Seebohm Rowntree’s original poverty surveys in the late-19th century. Yet it is a point that still receives too little focus in current debates.

There are two reasons why larger families are more likely to be in need of financial support: higher consumption needs, which are not reflected in wages; and greater caring responsibilities, which create constraints to labour market participation. These factors mean larger families will on average have a higher share of income from benefits in overall household income than smaller families, leaving them more exposed to changes in social security provision.

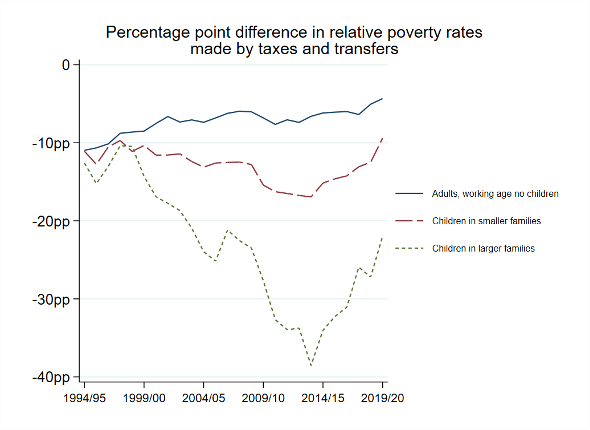

As a result, larger families saw the greatest reductions in their risk of poverty when social security support for children was expanded under Labour—and they have suffered most from the cuts to support since then. It is remarkable to see how closely changes in the effectiveness of the tax transfer system (see Figure 2) map onto the overall poverty trends in Figure 1. Social security benefits are both essential and effective in reducing child poverty.

Figure 2: Impact of the tax-transfer system in reducing relative poverty for different household types

Source: Authors’ calculations using HBAI 15th edition

Our research also has implications for the likely success of alternative anti-poverty strategies. The Conservatives have emphasised education and employment as solutions: in 2016 the government even removed income poverty targets from the Child Poverty Act and replaced them with indicators of worklessness and educational attainment. In fact, we find that parents in larger families have higher levels of education than ever before, and that they are working more than ever too.

Yet despite this, the risk of poverty has been rising in working households and most of all for larger families. This is even true where both parents work full-time, perhaps reflecting greater constraints on the jobs available to families with a more difficult work-care balance. There is work to do to improve the quality and flexibility of job options and to increase childcare access and affordability.

But our findings also challenge the assumption that parents must work ever more to pull themselves out of poverty. First, there is a logical flaw here: families with greater caring responsibilities are unlikely ever to be able to work as much as those with fewer care demands on their time, however affordable childcare becomes. There are also questions about whether they should be expected to, especially where parents want to prioritise the equally important and demanding work of parenting and care. Do we want it to be necessary for all parents to work full-time if they are to avoid poverty? Or would we rather live in a society where we can all make choices around the balance of care and paid work, especially when children are young?

The government’s argument for the two-child limit is that families who receive support from the benefit system should face “the same financial choices” as those supporting themselves solely through work. Our research suggests this is a nonsensical distinction. Very many—indeed most—larger families will need some financial support during this life stage, even when parents are in paid work. But this is a relatively short period of the life cycle, and a period in which adults are contributing in other vital ways. If we don’t embrace interdependence and life cycle redistribution, we accept that only the wealthiest families should be able to have more than two children, and that high and rising numbers of children will grow up in poverty simply because of their family size.

The project has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org