When we talk about ending freedom of movement, commentators tend to joke about workers leaving posh coffee shops, or fields of fruit going unpicked. But these stereotypes ignore the real cost. For this month's Speed Data, Jonathan Portes explores why ending freedom of movement could affect us all.

Continental know-how

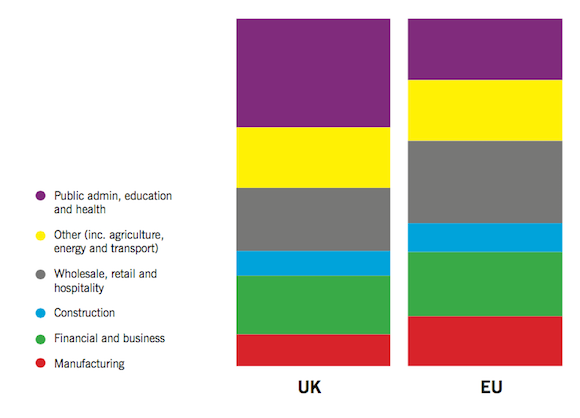

European workers aren’t just fruit-pickers and baristasSource: Author’s calculations based on ONS data

“Leave” campaigners claim that Brexit would curb “low-skilled immigration.” But most migrants from the European Union aren’t in low-skilled jobs. Indeed, migrants from “old” Europe—before the eastward expansion—are actually more likely than Brits to be in high-skilled jobs, while even for the most recent joiners, Bulgaria and Romania, less than a third are classed as being in low-skill posts. Overall, and just like Brits, most EU migrants work in middle-tier jobs—ranging from butchers to lab technicians. If we do curb migration by ending free movement, we’ll exclude many people doing productive, middle-income jobs: the sort of people you might think our economy needs.

Making things, making money and caring

Migrants are spread throughout the economy

The arrival of Eastern European labour into farms in parts of rural England has drawn attention and political heat, but agriculture is not a big employer these days, and it is pretty marginal for migrants too. More important is manufacturing—it employs 14 per cent of EU workers overall, which rises to over 20 per cent among those from Poland and the other “new Europe” joiners of 2004, double the proportion of Brits. “Old Europe” migrants are especially prevalent in finance and business services.

Overall, the state employs relatively fewer immigrants, but its dependence is rising. For example, only about one nurse in 25 is an EU migrant, but the proportion is far higher, a quarter or more, among the newest recruits. The same is true of social care.

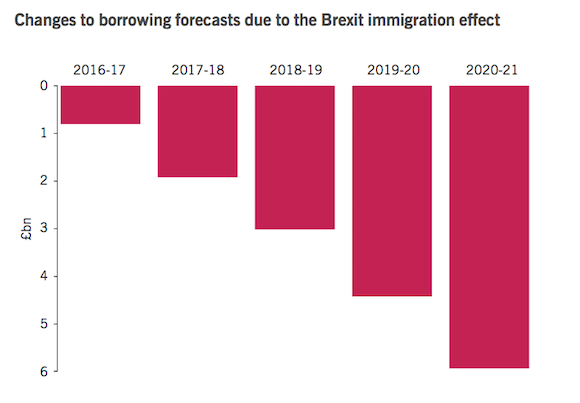

The drawbridge deficit

Locking out EU workers will plunge us deeper into the red

The Conservative manifesto promised to eliminate the deficit, but didn’t cost any of its policies. One was a pledge to reduce net migration to the “tens of thousands.” The Office for Budget Responsibility had taken Brexit into account and reduced its net migration assumption to 185,000, estimating that this would cost £6bn a year in lost tax revenue by 2020-21. If we imagine (generously) that reducing migration to within the 100,000 limit were a practical possibility, that would cost another £6bn a year.

While there is absolutely no certainty about when, or indeed, if free movement will end, immigration from Europe is already falling, because of the expectation of Brexit. Should, by some miracle, Theresa May hit her target, then the country will pay the price in many ways—including higher public debt.